1958, Indian, SC 1969.66

A Brief History of Mohan Samant's "Three Queens"

In this post, Brooklyn Quallen '25 discusses her research of Mohan Samant's Three Queens. Brooklyn is a STRIDE scholar currently working with Emma Chubb, Charlotte Feng Ford ’83 Curator of Contemporary Art.

As a student working in Curatorial under Contemporary Art Curator Emma Chubb, part of my job is researching works of contemporary art to add information to their object files. The object files are where we put all of the relevant information so that anyone who wants to do research can find it. This information includes exhibition history, artist interviews, and anything academic referencing the piece. Basically, it’s your one-stop-shop to find everything you need about a piece in the museum’s collection. Museum staff use them, but students can also make appointments to come in and do research with them.

Sometimes, though, there’s not a lot of information in those files. That’s where I come in. I do the research to help fill the files, finding those exhibition catalogs and newspaper clippings to print out and file for the next person who wants information. One such piece I did this for was Mohan Samant’s 1958 painting Three Queens.

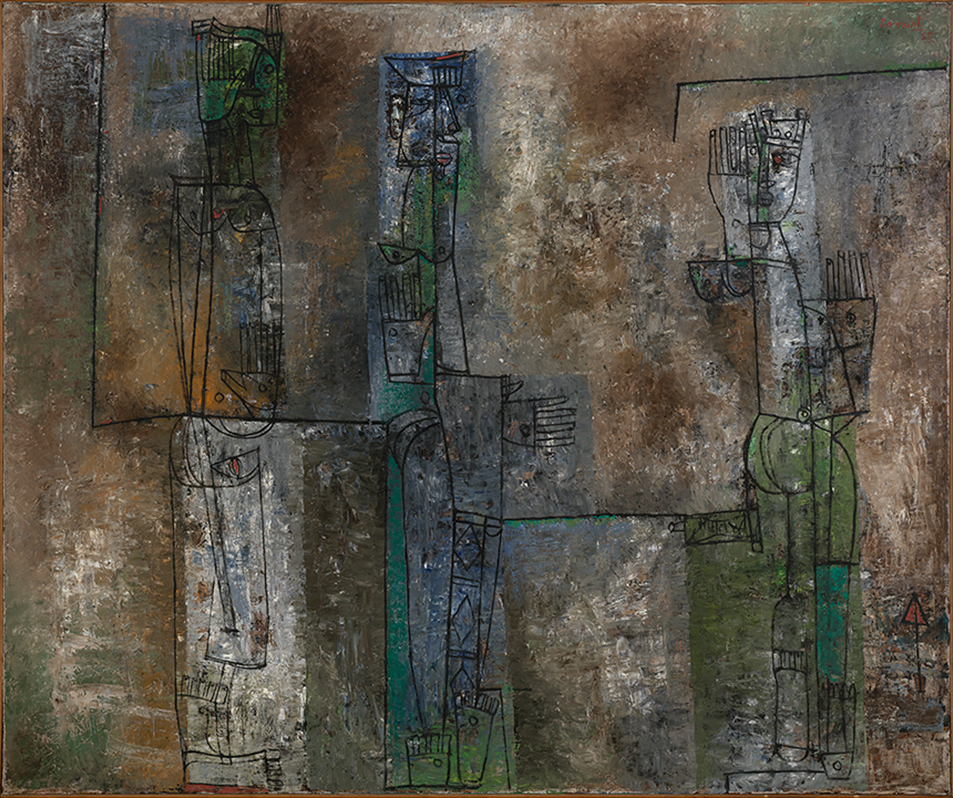

I first saw Three Queens in Then/Now/Next. It is a large, striking piece; upon seeing it, I was at once intrigued and confused. There are three abstract women, black lines on a dark, shifting background. The linework of their clothing calls to mind saris, and the red on their faces reminded me of my grandmother’s sindoor. But when I thought of all the Indian art I’d seen, I had absolutely no idea where this piece fit in. I’d never encountered Indian modernist artists like Samant before.

But when I went looking for more information, the SCMA’s file was almost empty. All that was in it was a short biography and a page of Emma’s notes. When I searched the SCMA database, I came up similarly empty handed. I had no idea where to start– until Emma told me an anecdote about how well-traveled the painting was. The piece had been created in India, she told me, and brought to the US when Samant came on a Rockefeller fellowship. It ended up back in India in the embassy sometime later, then made its way back to the US and into Smith’s collection.

Three Queens is one of Samant’s lesser-known works. It predates his Rockefeller fellowship that brought him to New York City and into the mainstream Western art world. It falls right after his travels to Italy on a cultural exchange scholarship awarded to him by the government, where he traveled and found inspiration in ancient forms. It was not included in the major shows he was featured in– Dunn International’s 102 Best Painters of the World, for example– nor was it in a museum collection until 1969. Even then, it came in as an anonymous gift and spent most of its time in painting storage.

I had next to no information. I had the SCMA database, Emma’s anecdote, and a biography of the artist. Still, I figured, how hard could it be? If the piece was in a museum, surely there would be a lot of information on it.

I started where any good search starts: by Googling it. Almost immediately, I found the digitized records of an Iowa City newspaper from 1959 that mentioned Three Queens. That was my first and only stroke of luck. Every combination of “Samant” and “Three Queens” in Google after that turned up nothing. So I tried looking into Indian mythology, where I knew Samant took inspiration for three queens. If you’re familiar with Indian mythology, you’ll know that that was a dead end path, too. Not because there aren’t references to three queens, but because there are so many! Without more information, there was no way I’d be able to trace the painting back to any specific inspiration.

From there, I started to look into the Rockefeller grant. I knew he received it in 1959, a year after Three Queens was painted. According to Emma, he’d brought it with him to New York. I just had to prove it. I started to look at exhibitions he did around that time in New York City to see if I could find the piece. Shoutout to the library staff for getting me almost all of the interlibrary loans I requested! That was when pieces started falling into place. Soon, I was able to put together a sketchy timeline– a Graham Gallery show here, a World House Gallery show there– up to 1961. I knew it came to the SCMA in 1969, so I was still missing eight years.

Samant’s estate published a biography in 2013, another thing the Smith library was able to get for me. Three Queens was not included in the list of all of Samant’s works– I know now that the estate didn’t have access to an image of it!-- which immediately had me panicked. However, it was referenced in the text, which allowed me to finally verify Emma’s embassy story. As part of MoMA’s Art in Embassies program, the Rockefellers lent it to Ambassador Galbraith in 1961 to hang alongside other modern art pieces in the ambassador’s residence in New Delhi, where it stayed until 1963.

After 1963, as far as I can tell, it was returned to the Rockefeller’s and stayed in their collection until it was donated to the museum in 1969.

In researching, you have to be open to whatever rabbit hole calls to you. In researching this piece, I fell down many– most completely irrelevant. But now I know that Thomas Hickey’s 1806 painting entitled Three Queens of Mysore was part of one of the earliest vaccination campaigns against smallpox in India. Now I know that John Galbraith, former US Ambassador to India, was an expert in early Indian art– and that one of his books is in the Hillyer Art Library. While these things don’t necessarily end up in the object file, they are all important to understanding Three Queens.

There are pieces of the story I don’t have, pieces that have been lost to time. Samant died in 2004. The internet, for all that it’s a great place to start researching, only has so much information– especially when you’re looking for records that predate it. The story may never be complete. I knew that going in, but I still chose to take on this puzzle.

Why this piece, then?

My grandparents are from India. I grew up as a part of that culture. I recognized the painted saris, the sindoors, because they look like what I wear to puja. I connected to this painting based on what I knew and what I could decipher, but I wanted to know more. I wanted to understand how it got here and why it was important enough to hang up in the SCMA. I wanted to know its story, and when it wasn’t in the object files, it only made me want to know it more.

It felt important for me to find this story, precisely because it hadn’t yet been found. In the SCMA’s collection, there is much less art by Indian artists than by White ones, despite the long and varied tradition of art in India. There is an underrepresentation of all people of color, something that the museum is trying to change. What I can do in the meantime, though, is help to make sure that these stories are there for those who want to find them.

So next time you see Three Queens, think about it in the context of cultural and transnational exchange. Think about the combination of tradition and innovation. Think about how it fits into the historical context of post-colonial India, and understand it a little better.

And next time you see a piece that gets you thinking, make an appointment with Curatorial to see the object file. You might be surprised at what you find.