Art as Archive: Curating Germany, 1918-1945

Rebecca McClung is a Ph.D. student in the history department at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Her work focuses on modern Germany and the memory of the Holocaust in a divided postwar society.

When I pushed through the heavy door into the works on paper storage, and held the artwork in my hands for the first time, it felt as if I were looking directly into history. After learning about many of these artists in a classroom setting, it was vastly different to experience the works on paper in their physical forms. Similar to research in the archives, there was no barrier between me and the art, and nothing separating me from the stories waiting to be told.

Working under the mentorship of Henriette Kets de Vries, the Manager of the Cunningham Center and the Associate Curator of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs, I had the opportunity to assist with researching and curating the upcoming exhibition Artists Under Siege: German Art 1918-1945. As a historian of modern Germany with an interest in museum work, I was delighted to join this project for the summer. I had the incredible chance to explore the museum’s extensive modern German art collection in depth.

Lotte Jacobi, printed by Carlos Richardson, Portfolio I: Lotte Lenya, ca. 1928 negative, 1978 print, gelatin silver print, 9 7/8 x 11 7/16 in., SC 1988.15.8.6.

I was excited to scour the collection to choose artworks for Artists Under Siege, and to look for works outside of the collection that could be potential loans. Researching to build the framework of historical and thematic context provided me with a chance to think through the presentation of the exhibition. Considering what we wanted to convey, how we wanted to do it, and what the art could tell viewers were important aspects of my work.

A comprehensive timeline of events, artists’ biographies, and other written reference materials for our framework were tangible products of the many hours I spent reading and thinking about this project. The timeline will serve as supporting media for the exhibition through the use of Timeline JS, an online tool used to build an interactive webpage. I also gained hands-on experience handling artwork, cataloging works in the internal database, and attending curatorial meetings that gave me insight into the profession and museum operations.

Otto Dix, Matrose und Mädchen (Sailor and Prostitute), 1923, lithograph printed in color on paper, 19 x 14 1/4 in., SC 1951.48.

As a Ph.D. student of German history, I came into this project very familiar with the historical context. Germany’s first republic from 1918 to 1933, called the Weimar Republic, is often characterized as a time of crisis. However, it also produced some of the most innovative minds of the twentieth century. Artists like Otto Dix (1891-1969), George Grosz (1893-1959), and Jeanne Mammen (1890-1976) were pioneers in the modern art movement, and are just a few of the big names included in this exhibition.

As the title Artists Under Siege suggests, the goal of this exhibition is to highlight their accomplishments within the context of the Nazi attack on modern art and freedom of expression. Since this exhibition encompasses both tumultuous eras of German history, my role was to figure out how to present German art against the backdrop of the roaring ‘20s, the rise of national socialism, and a world war. Most scholarship focuses on one era or the other, so I spent the summer researching both and determining how to bridge the gap. The artists themselves became the bridge. Living through these historical moments, their stories became the lens through which to cast the exhibition.

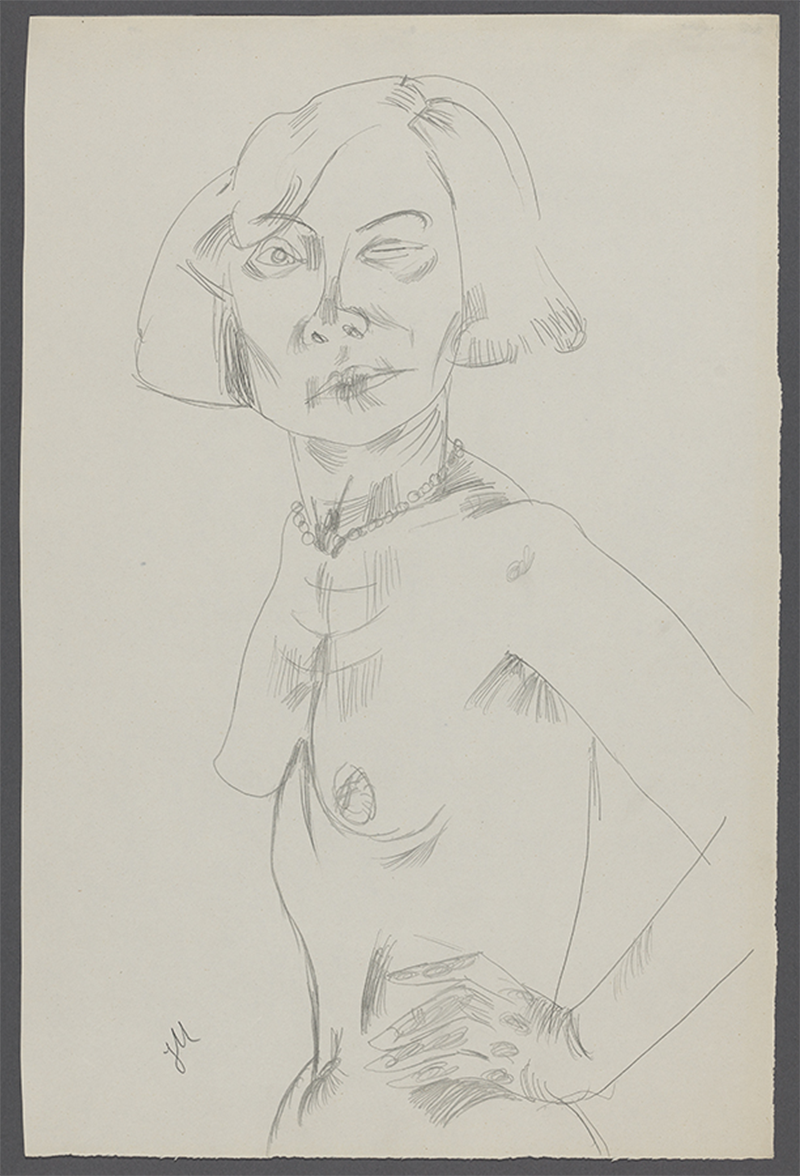

Jeanne Mammen, Woman Winking, 1930s, graphite on paper, 19 7/8 in x 13 1/8 in., SC 2021.16.3.

Through works like Woman Winking by Jeanne Mammen (1890-1976), the viewer is thrown into the thriving art and social scene of 1930s Berlin, but is also aware of the impending Nazi regime and Mammen’s decade of seclusion. For many artists, 1937 was a turning point in their careers, and represented the full threat against the arts. That year, the derogatorily titled Entartete Kunst Ausstellung (Degenerate Art Exhibition), organized by Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, presented art that he believed was ideologically opposed to national socialist goals. In doing so, Nazis used a social Darwinist lens to link modernism and abstract art to what they deemed degeneracy and mental illness.

Entartete Kunst is known today as one of the best exhibitions of modern art to exist, and many of the artists in Artists Under Siege were included in the original exhibition. Even if their artwork was not exhibited, much of it was still confiscated, and some destroyed, as part of the Entartete Kunst program. If being forced out of work in 1933 hadn’t halted artistic careers, this exhibition did.

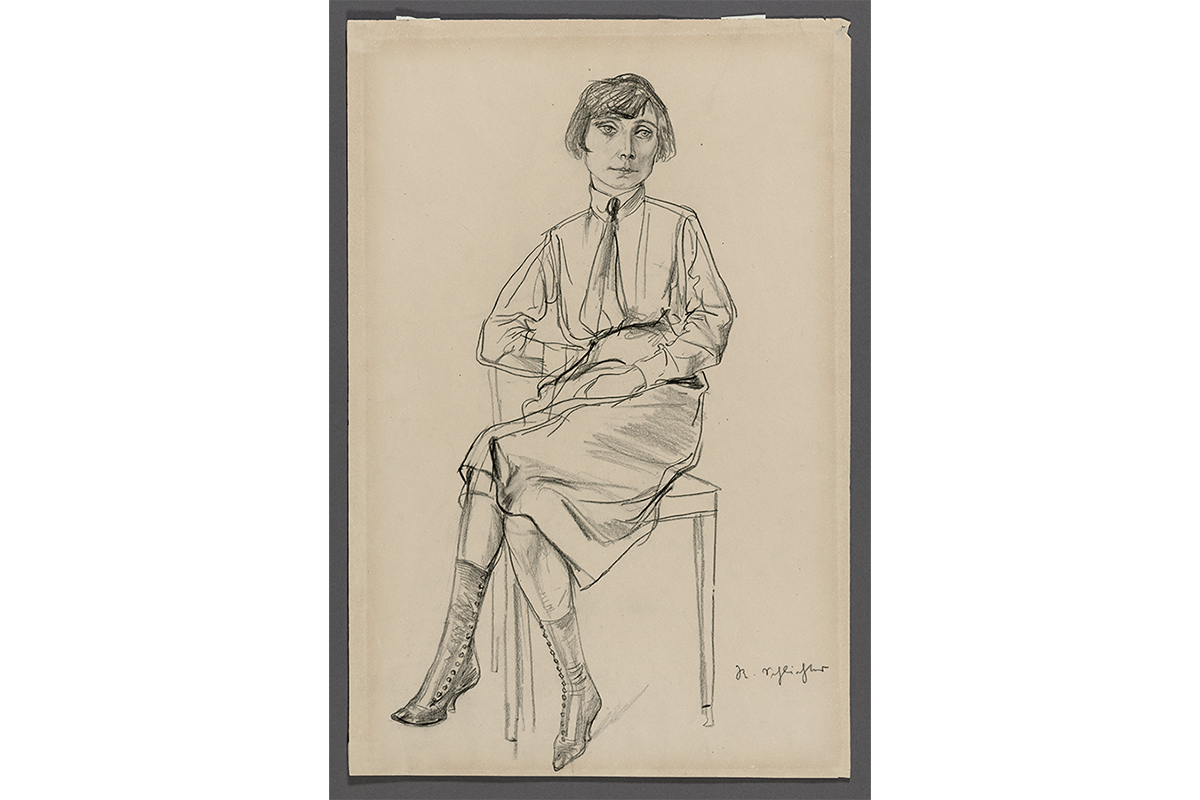

Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler, Portrait of Wolbers, 1929, charcoal and pastel on paper, 16 3/8 in x 11 3/4 in., SC 2021.16.2.

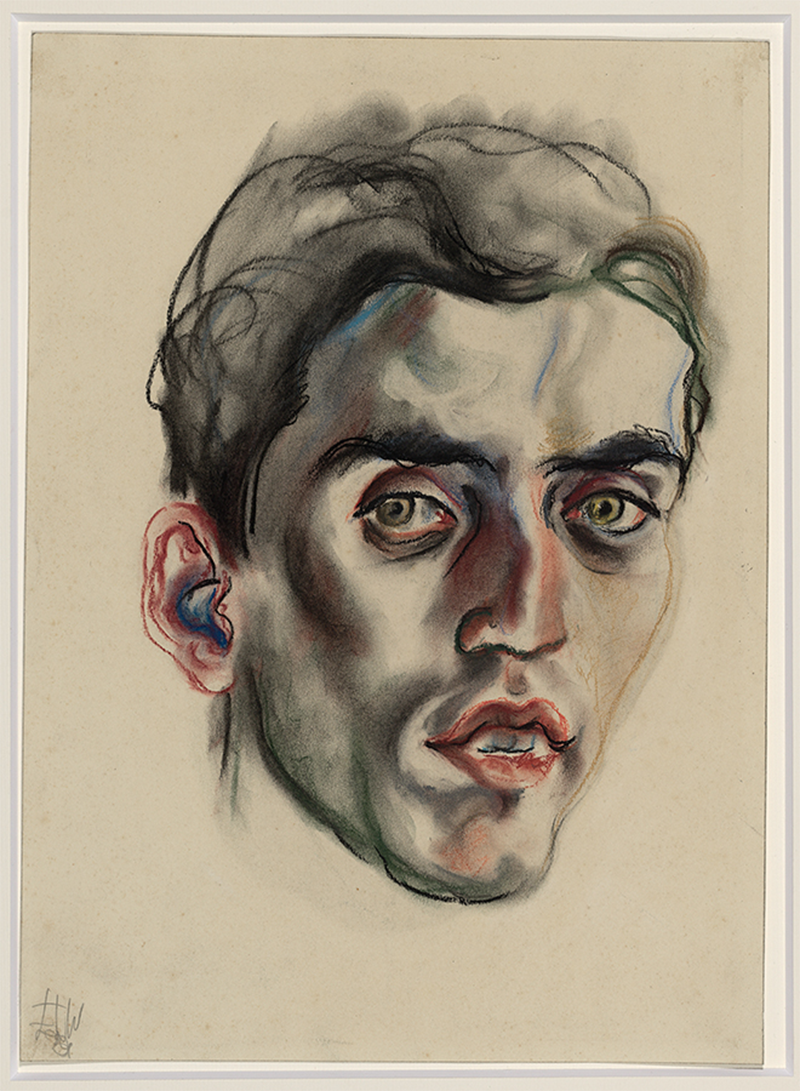

For Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler (1899-1940), the Nazis took something much more precious than her career. A member of the Dresden Secession Group of avant-garde artists, she suffered from schizophrenia and drew portraits of her fellow institution patients in a series titled Friedrichsberger Kopfe. Lohse-Wächtler was transferred to the Sonnenstein Euthanasia Centre in Pirna in 1940, and killed by gas as part of Aktion T4 – a euthanasia program developed in secret by the Nazis that killed children and adults with physical disabilities, those in institutions suffering from mental illness, and the chronically ill and aged.

As a woman artist with a tragic story, Lohse-Wächtler is often overlooked in scholarship, with work focusing on her death rather than her artistic talent. The quality of her work is clear in her Portrait of Wolbers. Portraying Wolbers with sympathy and subjectivity, the viewer is drawn to his distant expression. Simultaneously conveying the weight of the social and political context and telling Lohse-Wächtler’s own story, it is an accomplished piece of work from an underappreciated artist.

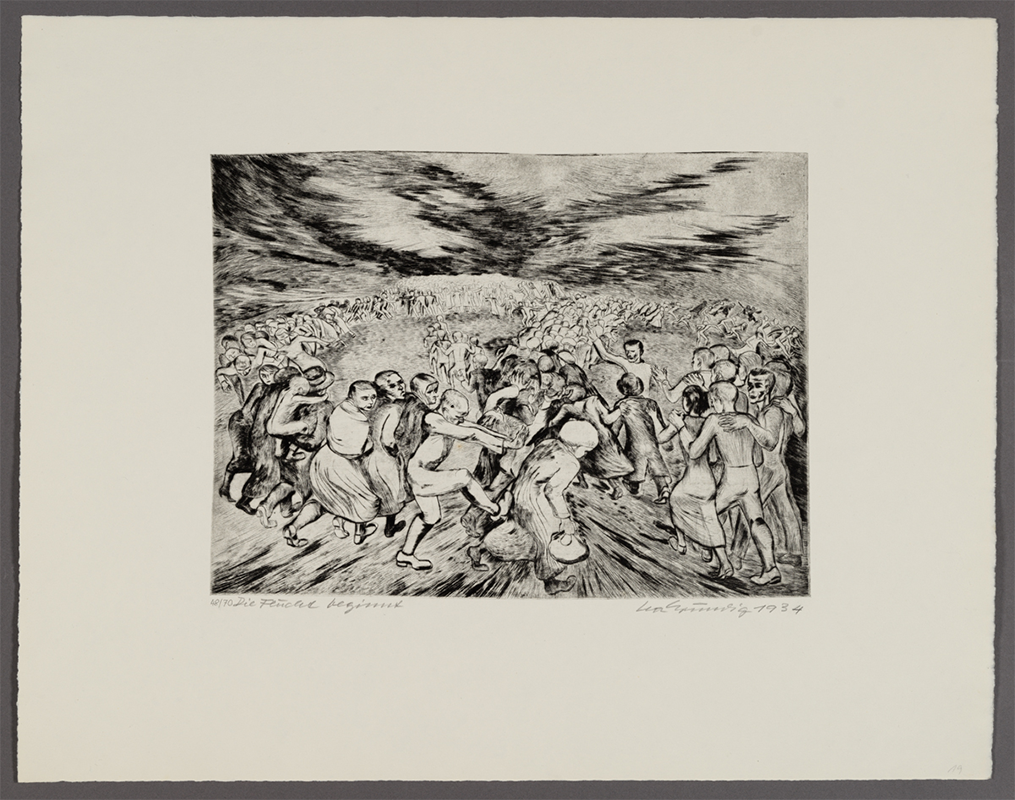

Lea Grundig Langer, Die Flucht beginnt (The Exodus begins), 1934, drypoint on paper, 9 11/16 x 13 in, SC 2024.32.5.

Others such as Lea Grundig (1906-1977) survived through emigration and actively depicted anti-fascist themes in their artwork. Grundig’s Die Flucht beginnt (The Exodus begins) printed in 1934 shows a large group of people walking in line through a barren landscape. They create a twisted and chaotic tapestry, illustrating the experience of fear and flight from the national socialist regime, searching for safety and finding none. Ultimately, they all seem to double back on themselves, with figures in the distance running aimlessly out of the frame. It is a picture of displacement and desperation, and a moving condemnation of the refugee crisis created by Nazi persecution.

These artworks are not just objects from a different time, but they are all fragments of lives lived under siege. The history stares back at you in the portraits, photographs, drawings, and prints that are just waiting to tell their stories. This exhibition project remains in its early stages, and I am very much looking forward to contributing to its further development.

To learn more about other recently acquired artists in this upcoming exhibition, please visit Fighting for Justice and Dying for Art: Lea Grundig Langer (1906-1977), an activist artist who risked it all and Karl Hubbuch Joins the SCMA Collection.