Fighting for Justice, and Dying for Art: Lea Grundig-Langer (1906-1977), an activist artist who risked it all

Henriette Kets de Vries is the Associate Curator and Manager of the Cunningham Study Center for Prints, Drawings and Photographs.

Art has always been instrumental in challenging the establishment. Historically, well-known European artists such as Francisco Goya or Honoré Daumier tackled hard issues by holding up a mirror and calling people out. Making art like this is never without danger. These controversial artists risk censure, imprisonment, or banishment, often working in total obscurity for the good of the cause.

One of these overlooked activist artists is Lea Grundig-Langer

SCMA first acquired a few of her and her husband’s prints as a gift from Gladys Engel Lang and Kurt Lang. With a recent gift from the Kallir Family Foundation of twelve prints by Lea Grundig-Langer and a newly purchased drawing, SCMA now has a good foundation of this nearly forgotten artist’s work.

Lea Grundig-Langer working in 1951

Lea Grundig-Langer’s fascinating life story demonstrates incredible courage and determination. Born in 1906 in Dresden, Lea Langer chose a different path from what her wealthy and strict Jewish Orthodox parents envisioned for their daughter.

Well before her marriage to the Gentile Hans Grundig, her father tried to dissuade her from her political beliefs and her unsuitable boyfriend. Nonetheless, nothing would turn her away from her ardent political convictions and her love for Hans. After her studies at the School of Arts and Crafts and the Academy of the Fine Arts in Dresden, Lea and Hans joined the ASSO (Association of German Revolutionary Artists).

Life as a starving artist was not easy but filled with conviction and railing against the rise of the Nazi party. The Grundigs focused on printmaking because the medium was perfect for spreading information and ideas. Hans and Lea bought a table-sized printmaking press to create their political prints at home to reduce the risk of detection. Lea and Hans lived among the poorest of the city, and it was among those people and the dire circumstances of their lives that Lea found her inspiration. Lea’s prints offered her a way to address issues such as women’s rights, unemployment, and the increasing power of the National Socialist Nazi Party. Many of her works emphasize the humanity, or lack thereof, in everyday intimate scenes. In other works she more directly attacked the Nazi regime―a very risky path, as she knew all too well.

In the print series Under the Swastika, The Jew is Guilty and War Threatens Lea directly confronted Nazi rule and their attitude towards Jews, Communists, and other targeted groups. Her Women’s Life series focused on the plight of hard-working poor women during the rise of the Nazi regime.

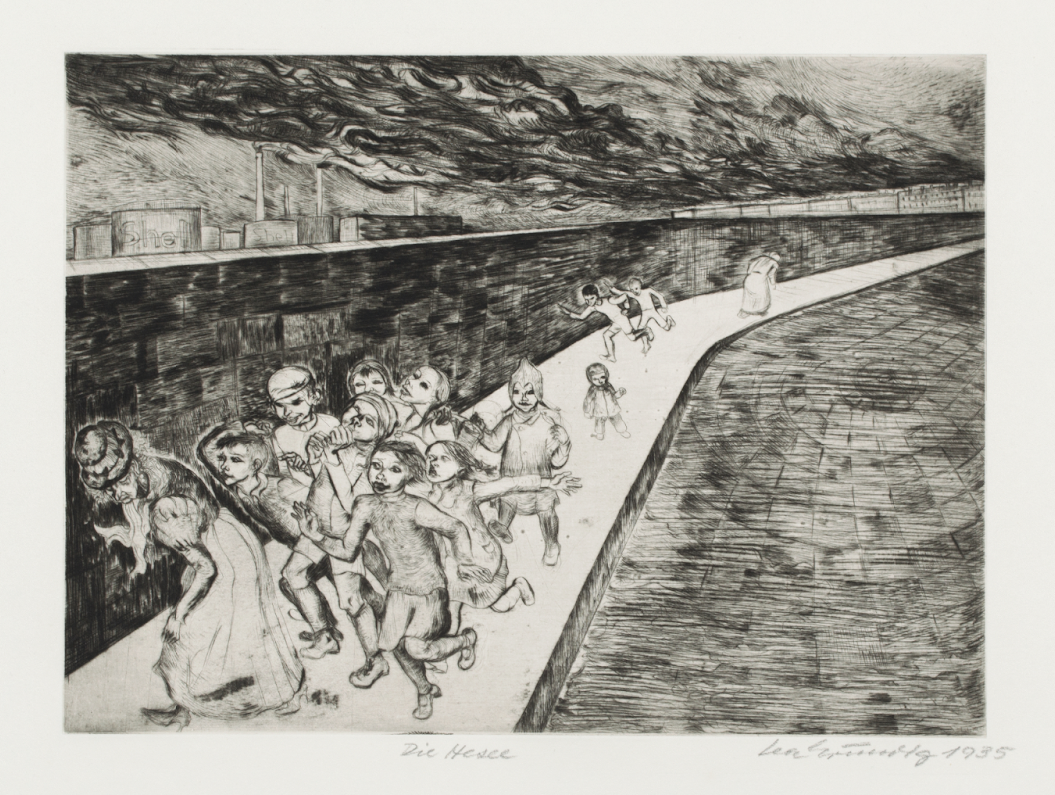

Lea often included children in her art to show where prejudice comes from and how it affects young minds. By depicting kids playing, she highlighted the disturbing truth that societal biases can sneak into their innocent games and interactions. This focus on prejudice was significant during a time when fascist beliefs were growing, as it stressed the need to confront and break down these harmful ideas before they could influence the next generation. Through her artwork, Lea encouraged viewers to think about how their beliefs impact children, urging them to consider the social environment around them. Her print, The Witch, depicts a group of children taunting an old woman as they follow her on a long path set against a dystopian landscape. This dark “fairytale” serves to illustrate the juxtaposition of childhood innocence with the darker undertones of societal issues.

Lea Langer Grundig, German, 1906-1977

The Witch. 1935

Etching and drypoint on medium-weight, smooth cream colored paper.

Gift of the Kallir Family Foundation

SC2025.6.11 (on view now)

Guided by the warped vision of Reich Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, the Nazis understood the power of the Grundigs’ images and, in 1936 they were arrested for the first time. Over the next four years, as the Grundigs were repeatedly incarcerated and released, the importance and danger of their art became increasingly palpable as they continued to contribute to the underground art movement.

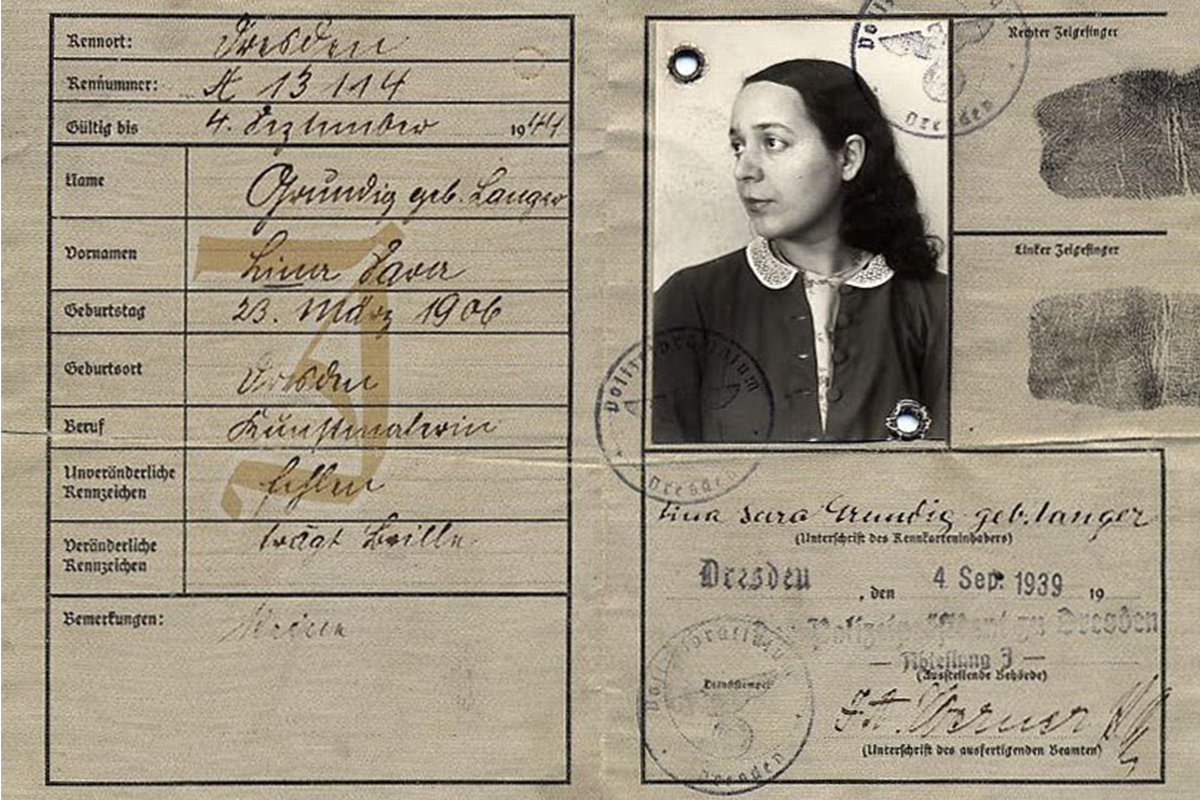

Memorandum of the Dresden office of the Gestapo ordering the provisional arrest of Lea Grundig; Inv.No. Do 62/1126.3 from the Deutsches Historischen Museum

In 1939, the Gestapo finally arrested and then expelled Lea Grundig from Germany and escorted her to a transit camp in Slovakia Bratislava, (a satellite state of Nazi Germany at the time). With the help of Major Berthold Storfer, whose negotiations with Eichmann saved ten thousand Jews, Grundig boarded the Pacifique, one of four old ships carrying a total of 4,000 Jewish refugees destined for Palestine. Upon arrival, the British authorities (Palestine was under British Mandate) rejected the refugees. They forced them onto a large new ship, the Patria, to be sent to a prison camp on the island of Madagascar. However, Haganah, a Zionist underground organization, decided to prevent this by blowing a hole into the bow of the boat. Unfortunately, the explosive charge was too large, causing the boat to sink rapidly, and many people drowned. Lea witnessed the catastrophe but survived and was placed in a British internment camp near Haifa for nearly a year due to her status as an illegal German immigrant. After a year, she finally found refuge in Palestine with her sister.

In the meantime, Hans was imprisoned in 1940 at the Sachsenhausen concentration camp in Oranienburg near Berlin. He was released in 1944 and assigned to a frontline battalion as a soldier, but he deserted immediately and joined the Russian Red Army instead. He did not return to Dresden until 1946. Lea kept working as an artist, illustrating children’s books but also creating antifascist works that directly confronted the horrors as told by the people she encountered in Palestine. Again in hot water, she would be regarded as a Zionist and simultaneously an anti-Zionist, befriending and inspiring Israeli and Palestinian artists alike.

It would not be until 1946 that Lea would learn that Hans had survived, and not until 1948 that she would finally be reunited with him in Dresden.

"And then he stands before me, my old gray Hans," she wrote in her memoirs. "He is ill, and in his small face, one can still see the frightful tensions of those terrible years. His hair has gone totally white—but his straight mouth is laughing, as before."

Finally, back in Dresden, her hometown, leveled to the ground by the war, she once again had to adapt and deal with the new authorities in charge. She continued to be a force in the art circles, becoming the first female professor and chairholder at the New Dresden Academy of Fine Arts, rubbing many the wrong way, but I leave that for another chapter.

Lea Grundig’s print, The Witch will be on view on SCMA’s third floor from May 6 - November 2, 2025.