Visiting James Ensor

Henriette Kets de Vries is the Manager of the Cunningham Center for Prints, Drawings and Photographs and Assistant Curator of Prints, Drawings and Photographs at SCMA.

A couple of years ago I ventured out on a small personal pilgrimage to visit the hometown and gravesite of an artist whom I consider to be one of Belgium’s best; James Ensor (1860–1949).

Since I’m originally from the Netherlands, I’m quite familiar with the neighboring country of Belgium, however I had never been to the seaside town of Oostende. I was very excited to discover Ensor’s old stomping grounds.

Ensor spent most of his life in Oostende with the exception of two years where he studied at the Academie Royal des Beaux-Arts in Brussels only to return completely disillusioned, referring to the Academy as the "establishment of the near blind.” It was in Oostende where he was inspired to create his unique artistic vision.

Oostende is one of many interesting but forgotten Northern seaside places which used to draw a rather sophisticated crowd in the 19th-century.

Its glorious past lingers only faintly in the large, now dilapidated, buildings which immediately bring on a rather melancholic feeling, especially on a dreary fall day.

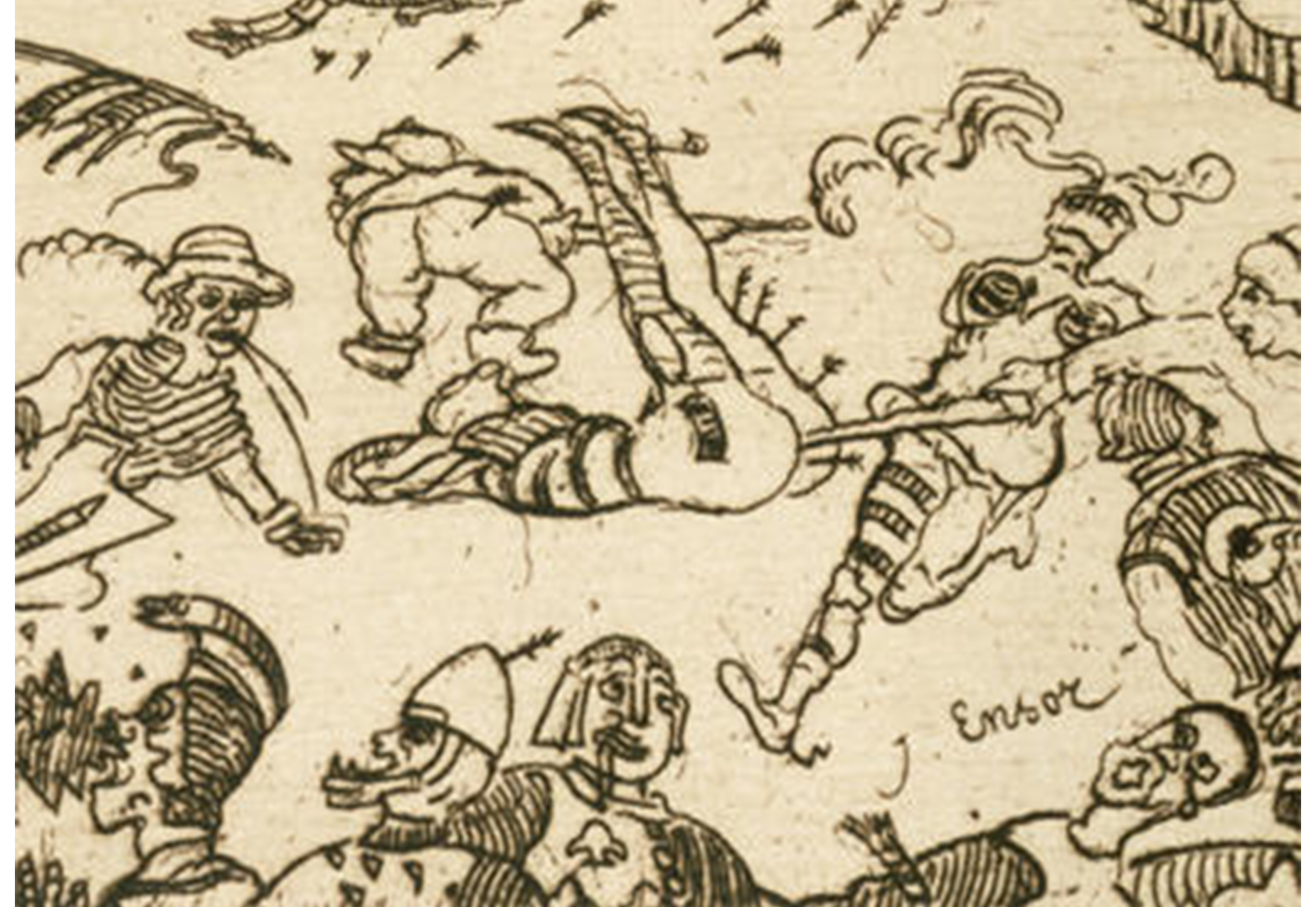

While known for its seasonal lively carnival crowds, a spectacle often displayed in Ensor’s art, historically, it is a rather dark place. Coveted because of its strategic location, it was frequently destroyed by invading armies. It was also the site of the bloodiest battle of the Eighty Years War and it is rumored that human bones are still to be found in its dunes. Ensor was clearly intrigued by these battles, as he drew quite a few of them. The Smith College Museum of Art owns a small etching called La Bataille des Èperons d'Or (The Battle of the Golden Spurs) from 1895 – a darkly comical, cartoonish rendition of a famous Flemish battle which took place in 1302.

Detail of La Bataille des Èperons d'Or.

For many years, Ensor fought his own personal battles with the local arts establishment, until finally the tide turned in his favor. During his early years, his work was mostly rejected and he was regarded to be eccentric and quite a loner. Later in life, after he had turned into an old, dignified, and white-bearded man, he was often seen wandering the broad boulevard.

Society finally caught up with him and his art and he came to enjoy the fruits of his labor during his lifetime – an outcome not often enjoyed by such a recalcitrant visionary artist.