What Happens When Feminist Scholarship Meets the SCMA Collection

Zoey Ochieng ‘28 is a Statistical and Data Science and Economics Major. She has worked as a Student Engagement Assistant at the SCMA since 2024 and as an Interpretations Intern last summer.

Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism, an intersectional feminist journal based at Smith College, turns 25 this year. To celebrate, the journal collaborated with the Smith College Museum of Art and eight Smith undergraduate students to pair articles from an upcoming issue with works from SCMA’s collection. I worked on this project as one of the paid student collaborators. On view now until March 2026, our pairings are on display with label texts that we wrote inviting visitors to see the two in conversation.

Our first meeting was a mix of abstract summaries and big ideas. We each read through a stack of abstracts and, eventually, full articles. Two pieces grabbed me: one on Ugandan activist Stella Nyanzi’s controversial poem (I had studied her before. I’m a huge fan.) and an interview with scholar Naminata Diabate on defiant disrobing.

Both explored the female body as a stage for expressing outrage, but Naminata’s take hooked me. She described naked protest as a bold, deliberate act. Risky? Yes. Easily sensationalized? Also yes. But, she argued, in that vulnerability lies power. The protestor owns the moment, no matter how it’s received. In past classes, we often framed that vulnerability as weakness. Here was someone flipping the script. I was sold.

Photo by Zoey Ochieng.

Armed with Naminata’s ideas, I dove into SCMA’s database, determined to find the perfect pairing. Days turned into weeks of scrolling and squinting at the museum database. Finally, I met with Aprile Gallant, SCMA’s curator of Prints, Drawings and Photographs and frankly, a walking encyclopedia of works on paper. By the end of our meeting, I had two contenders.

Photo by Zoey Ochieng.

At our third cohort meeting, students gathered in the Cunningham Center where our chosen works were hung thematically. Many of us had not settled on our final picks, and so we appreciated sitting with the real artworks rather than the digitized version (we all know how that goes, hi my dating app people) and did a small writing activity connecting our articles with the artwork. We then sat in groups to share our observations. When it was my turn, I blurted out the question haunting me since day one: Is being disruptive enough if the meaning is lost? That question sparked a group discussion, and by the end I had settled on Lesley Dill’s A Word Made Flesh (Front). Throughout my search, I had been focused on finding an artwork that answered that question. But the conversation helped me realize that maybe it’s just as valuable to hold the question open.

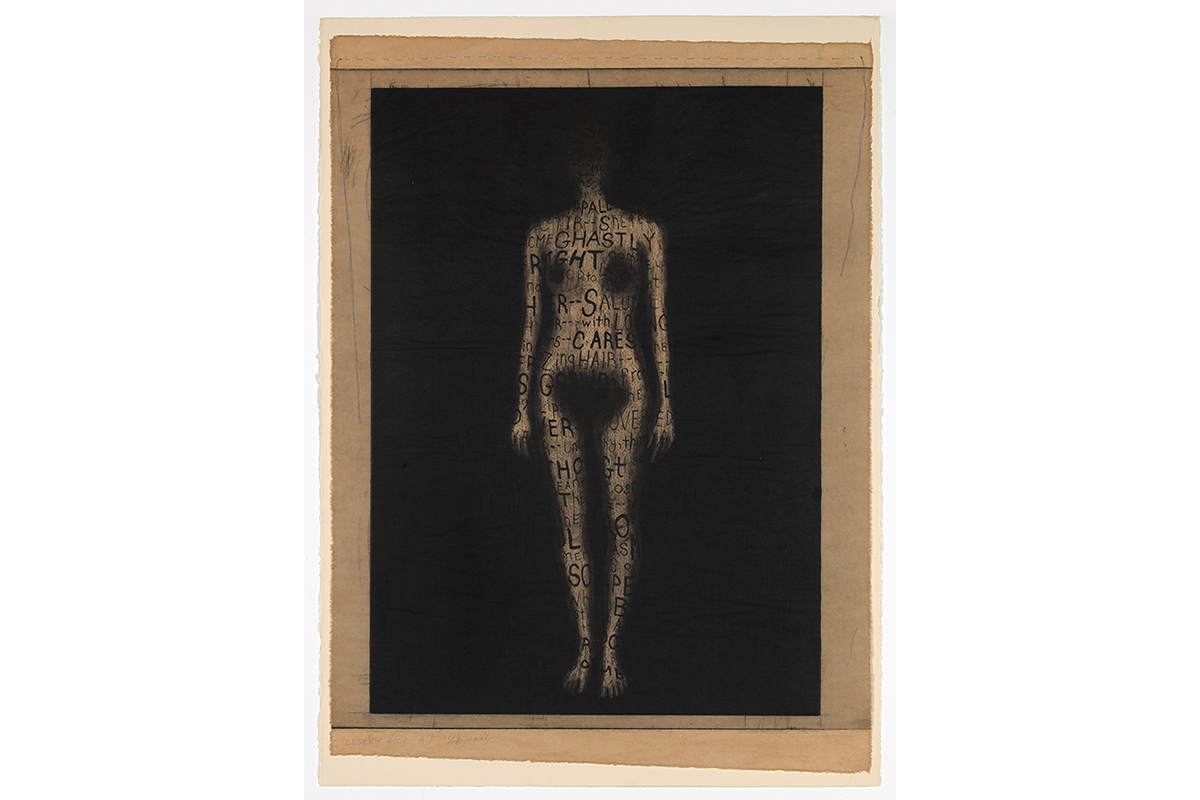

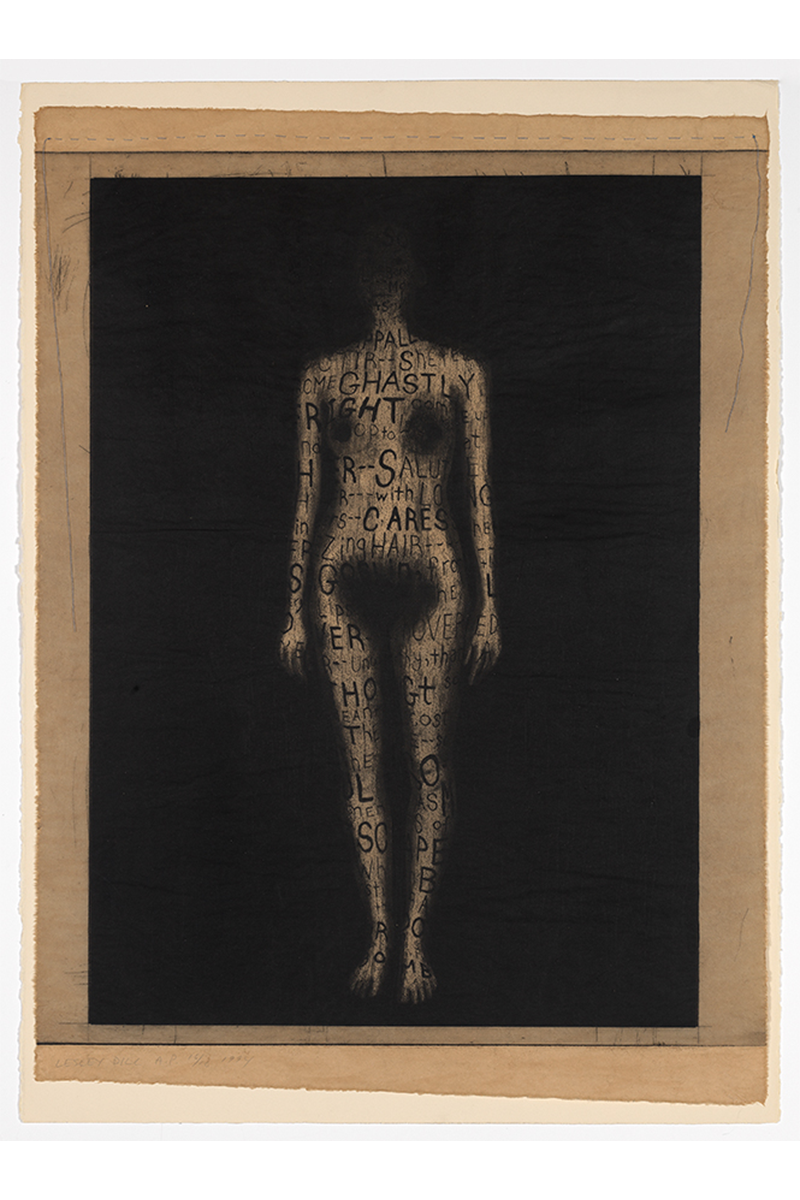

Lesley Dill, A Word Made Flesh (Front). 1994. Lithograph and intaglio on Mulberry paper. Lesley Dill Print and Multiple Archive. Gift of Lesley Dill ⓒ2025 Lesley Dill. Courtesy of the artist.

Picture this: a delicate, tea-stained sheet of Mulberry paper (I’ll give you a second to Google it), stitched with thin blue thread onto heavier paper. Emily Dickinson’s words are written across the body of a nude figure, the body becomes a page, the page becomes a body. Like the protesters Naminata writes about, the figure in Dill’s work demands an audience. Both make you pause and read. Yet the question persists: What if the disruption doesn’t direct attention where it’s intended? That tension is exactly why this pairing works for me.

Our final step was to write a label for our chosen artwork. It had to be around 125 words. I had two pages of notes and was convinced every sentence was crucial for “the plot”. Enter Jessie, SCMA’s Associate Director of Education and Interpretation, who led a label-writing workshop. With Jessie’s help, I wrestled my two pages into 190 words (yes, still over the limit, but I consider that a moral victory). Somehow, the essence of Naminata and Dill’s shared themes was still there.

Working on this project shifted my thinking about how we measure protest “success”. If a naked protest is misinterpreted, does it still matter? It also deepened my appreciation for the way scholarship and art can spark each other. It’s like setting up two strong personalities on a blind date. You don’t know if they’ll clash or make magic, but either way, something interesting is going to happen.

This fall, you can see all the student pairings at SCMA. Maybe you’ll discover unexpected connections between the artworks and the articles. Or maybe, like me, you’ll leave with better questions.