The Ancient World Gallery

The Ancient World Gallery offers new ways of viewing ancient objects. The definition of the term “ancient” differs according to each culture’s history. Often the designated periods do not align with one another. Yet, despite originating in various political, social and religious structures, the objects on view have similarities. Spanning many cultures and several millennia and encompassing a wide range of materials, these works are grouped according to function and style and represent common themes, such as powerful figures, luxury and ornamentation, everyday life and the afterlife. The gallery also contains a case of ancient Greek, Roman and Chinese coins. A digital map locates selected objects in their original areas of creation. It offers more information about some of the works on view, compares their materials and provenance and highlights cross-cultural connections.

While this gallery enriches our understanding of the ancient world, the display also presents certain challenges. SCMA endeavors to be transparent about the problems related to collecting and exhibiting ancient art in the modern era, including issues of previous ownership, the treatment of funerary objects and authenticity.

The ancient world gallery offers evidence of the creativity of human civilization throughout history. It also tells the story of SCMA itself, highlighting over a century of collecting ancient art through purchases, gifts and bequests.

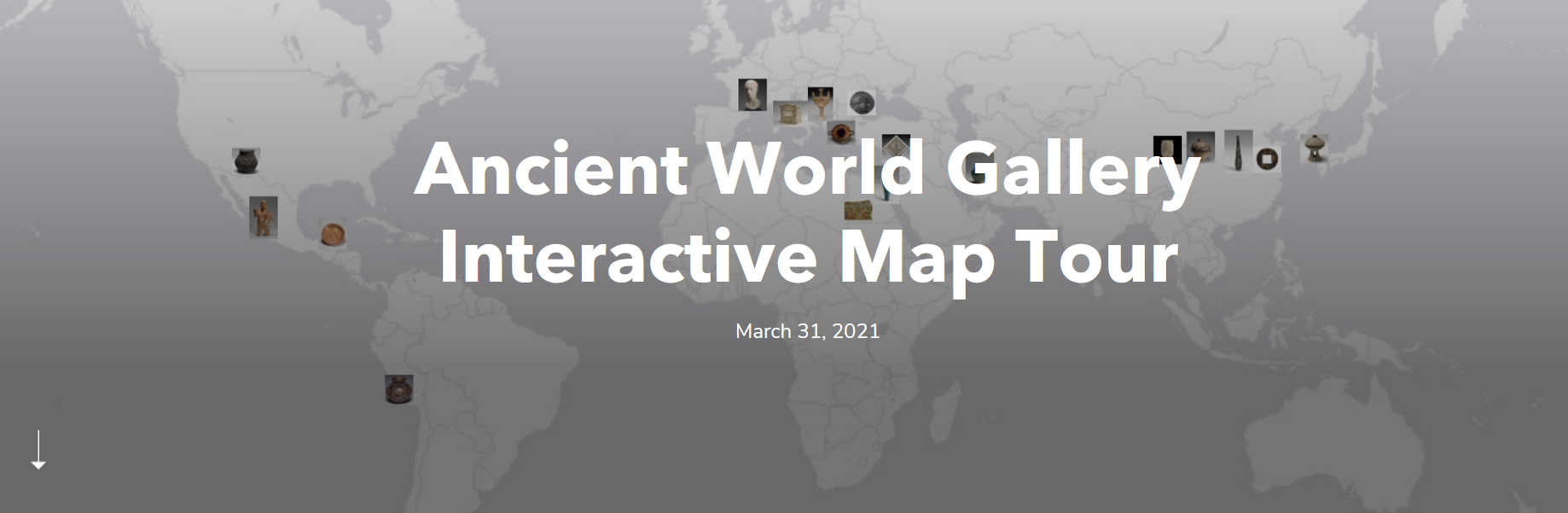

Throughout the ancient world, objects fashioned from clay served a variety of practical and ritual purposes. The ceramic vessels on view functioned in similar ways, storing food or liquid that could be consumed by the living or offered to the dead. Their shapes and production techniques are nevertheless specific to the time and place of their creation, representing the ancient civilizations that once prevailed in the lands of present-day China, Greece, Korea, Peru and the United States.

Unknown. Peruvian; Nazcan. Vase. 400–1000 CE. Terracotta. Body diameter: 5 ⅜ x 6 ⅛ in. Gift of Mrs. Clayton O. Braatz (Margaret Vanston, class of 1937). SC 1980.50.2

Because stone was hard to transport, the stone sculpture of particular cultures was determined by what was locally available. Ancient sculptors thoughtfully utilized the qualities of local stone for aesthetic reasons as well as for meaning. The pure white marble from Mediterranean quarries, for example, was ideal for many Greek and Roman sculptures of gods. It also provided a blank canvas for the addition of color (now lost), as was the common practice of the time.

Unknown. Greek. Winged Torso of Eros. 1st century CE; Roman Imperial period. Marble. Height: 21 in. Purchased with the Winthrop Hillyer Fund. SC 1922.28.1

Objects created for daily use reveal much about ancient peoples’ beliefs, practices and habits, both secular and sacred. For example, the Etruscan and Greek drinking cups held wine consumed during social gatherings. When raised to the mouth, the Greek “eye cup” doubled as a mask with prominent eyes to ward off evil. Otherwise, emptying the cup would bring the drinker face to face with a Gorgon, whose gaze was said to turn people to stone. Also on display are Chinese and Greek mirrors that were made for daily use and traded as luxury items, as well as objects bearing ancient writing.

Unknown. Greek. Kylix (drinking cup) with Eye Design. Late 6th century BCE. Terracotta with black, red and white glaze. 11 ½ x 8 11/16 x 4 ⅛ in. Gift of John Dusenbery in memory of Elsbeth Dusenbery (Elsbeth Brainan, class of 1940). SC 2004.20.16

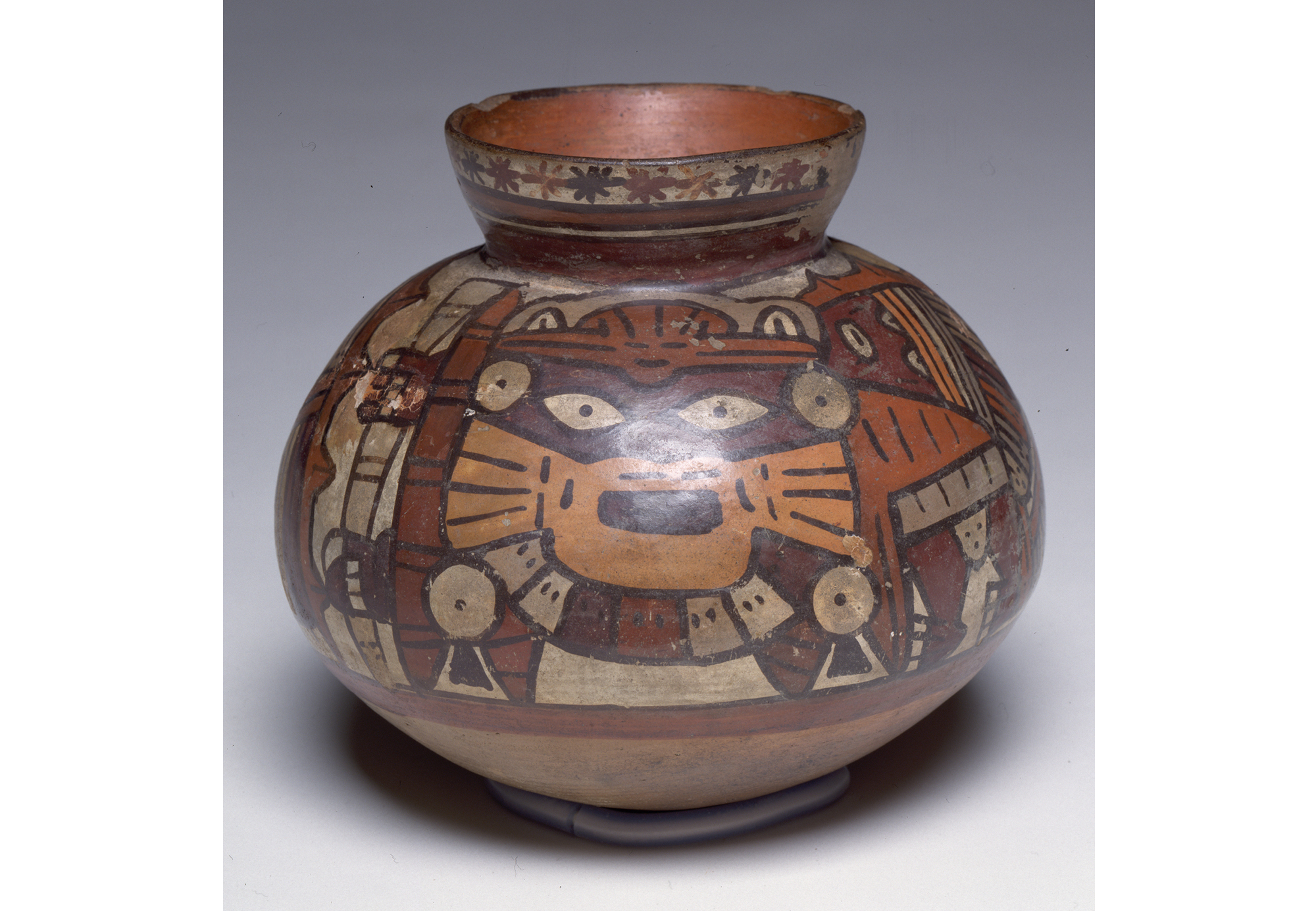

Because many of these objects were discovered in tombs, it is not always clear whether they were created for use in daily life, the afterlife, or both, therefore blurring the boundaries of their original function. Some objects were intimately associated with the deceased body, such as the brightly painted Egyptian cartonnage fragment. A protective cover for a mummified body made of plaster-coated linen, this cartonnage illustrates gods and goddesses guarding the soul of the deceased (in the form of a bird on the front of the boat) as they accompany it into the afterlife. Jade articles were common tomb furnishings in ancient China.

Unknown. Egyptian. Fragment of a Cartonnage Mummy Cover: Goddesses Towing Funerary Boat with Figures of Osiris and Mourning Isis and Nephthys. c. 100 BCE –50 CE; Late Ptolemaic or Early Roman Period. Tempera on cartonnage (fibrous cloth coated with plaster). 9 ⅞ x 14 in. Gift of Emily M. Williams. SC 1918.6.1

In this case are a variety of figures, including a significant number of female ones, which were deified, idolized or believed to possess extraordinary power or magic in their respective cultures. The awe-inspiring demon quellers, for example, often stood sentinel in pairs near Chinese tomb gates. These powerful and magical figures range widely in their materials, from clay to volcanic stone to marble. This case display also highlights the contrasting scales of the figures, corresponding to the particular contexts in which they were used.

Unknown. Chinese. One of a Pair of Tomb Guardians. Tang dynasty (618–907 CE). Earthenware with painted decoration. 22 x 12 in. Gift of Donna Smith Reid, class of 1951. SC 2016.67.15.1

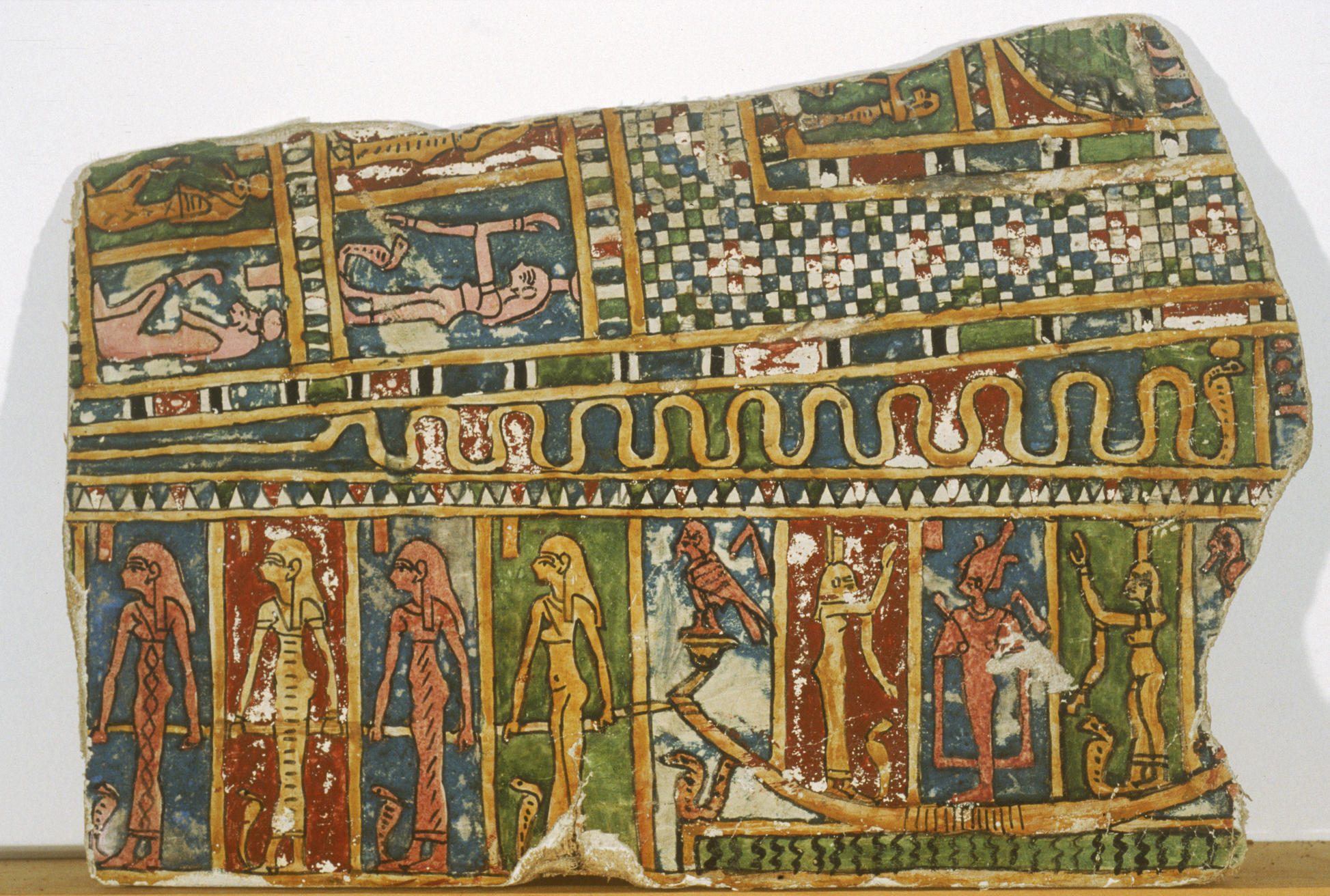

Almost all ancient cultures exalted courageous spirit and physical strength. A Roman terracotta bas-relief featuring Hercules, an Etruscan bronze discus thrower, and a Mesoamerican carved stone helmet in the shape of a stylized skull head are all objects in this category. The helmet, known as a hacha, was most likely made for ball game rituals or put on display. War being a frequent occurrence in the ancient world, warrior figures were also glorified in many civilizations.

Unknown. Mexican. Hacha (helmet). 600–900 CE. Stone. 7 ¾ x 2 ½ x 5 ⅞ in. Purchased. SC 1935.9.1

On view here are a variety of precious materials that would have drawn attention to the bodies or objects they adorned. Jewelry was worn directly on the body, while other objects decorated furniture. Some cultures exchanged such luxury goods via land and maritime trade networks such as the Silk Road and the Spice Route. In addition to serving the functional purpose of keeping clothing in place, the Sino-Siberian belt plaque was highly decorative. The stylized design ingeniously incorporated a small tiger underneath the big one, as if nursing.

Unknown. Sino (China)–Siberian, Ordos region. Animal Belt Plaque: Tiger. Iron Age (5th–2nd century BCE). Bronze. 1 ⅝ x 3 ⅜ x 7/16 in. Purchased. SC 1958.13

Metal coins, made of copper or copper alloys, were the basic form of currency in China for more than 2,000 years. They come in a number of shapes such as that of a knife or spade. Inscriptions denoting value include information such as weight, currency name, and imperial reign name. Greek and Roman coins, on the other hand, were struck from gold, silver, copper, and tin or zinc alloys. The two sides are decorated with imagery of leaders, deities, animals, plants or buildings and are often related to one another. The character of a portrayed figure could be emphasized through the inclusion of a motto, personification, inscription or attribute.

Unknown. Chinese. “Ming” Knife Money of Yan State. Eastern Zhou dynasty, Warring State period (475-221 BCE). Bronze. 5 ½ x ⅝ x 1/32 in. Gift of Ginling College. SC 1922.34.14

This installation is supported by The Maxine Weil Kunstadter, class of 1924, Fund and the Nolen Endowed Fund for Asian Art Initiatives.