Aaron Siskind and Abstract Expressionist Photography

Guest blogger Catherine Bradley '17 is a Smith College student, class of 2017. She is a Student Assistant this summer in the Cunningham Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings and Photographs.

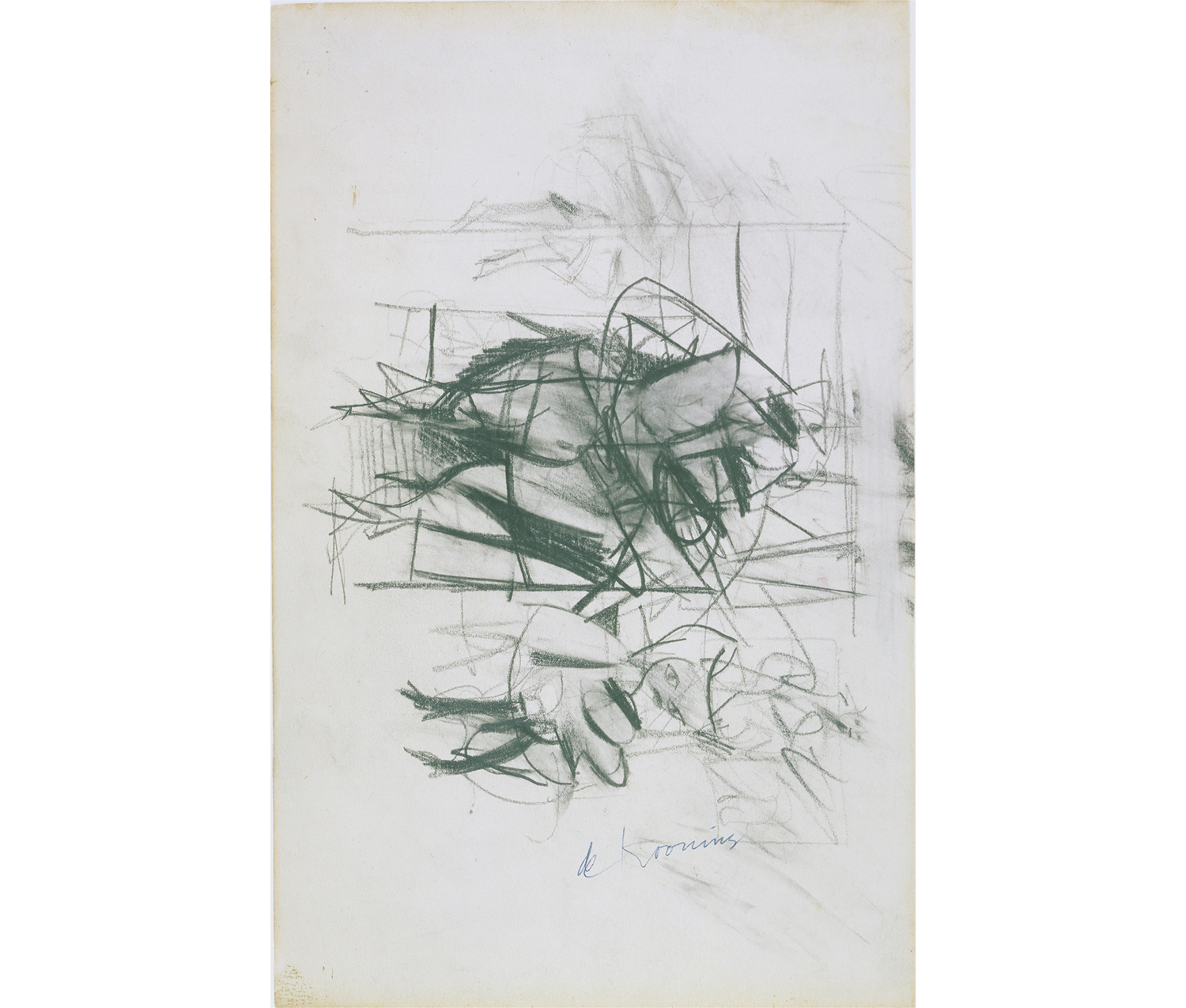

The Abstract Expressionist movement emerged in the 1940s, amidst the chaos and aftermath of World War II. During this global crisis, American artists such as Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Barnett Newman, and Jackson Pollock broke away from typical art conventions and opted to focus on movement, improvisation, and spontaneity in their works. After World War II, many European artists fled to America, further influencing the new style characterized by bold, black strokes and an emphasis on inner emotion and expression.

Willem de Kooning. American, 1904–1997. Women, ca. 1950. Graphite on cream wove paper. Gift of Mrs. Richard L. Selle (Carol Ann Osuchowski, class of 1954). SC 1969.46.

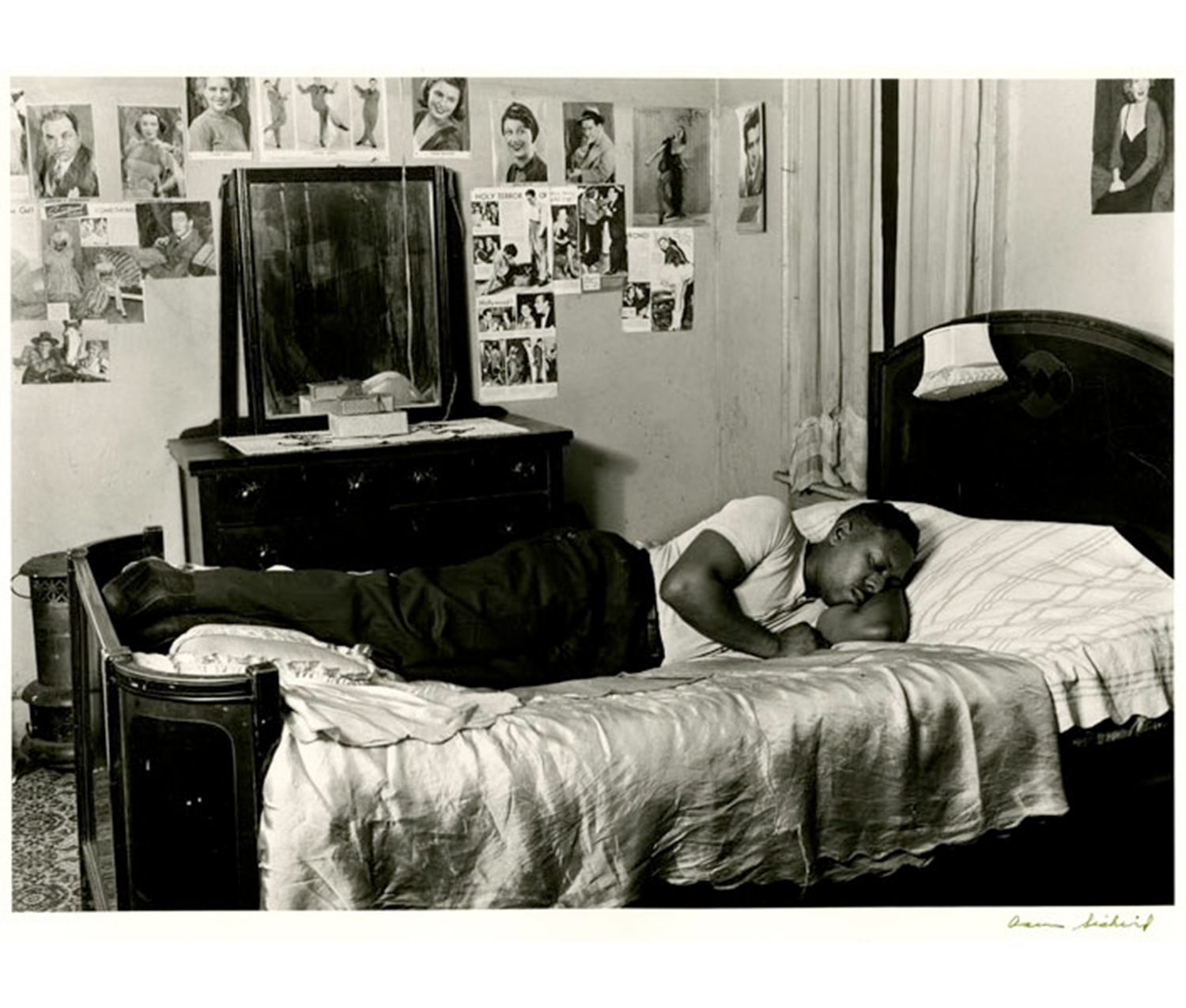

But during the initial boom, Abstract Expressionism was largely limited to drawing and painting. Photographers of the day were largely focusing on documentary subjects. As a member of the New York Photo League in the 1930s and the head of the group’s “Feature Series,” Aaron Siskind created series such as The Harlem Document, Portrait of a Tenement, and St. Joseph’s House: The Catholic Worker Movement. These photographic essays sought to portray the social, economic, and political conditions of its subjects, keeping in line with the League’s mission to link social commentary with art.

Aaron Siskind. American, 1903–1991. Man on Bed, 1940. Gelatin silver print. Gift of Leonard A. Fink (Class of 1952). AC 1984.74.12.

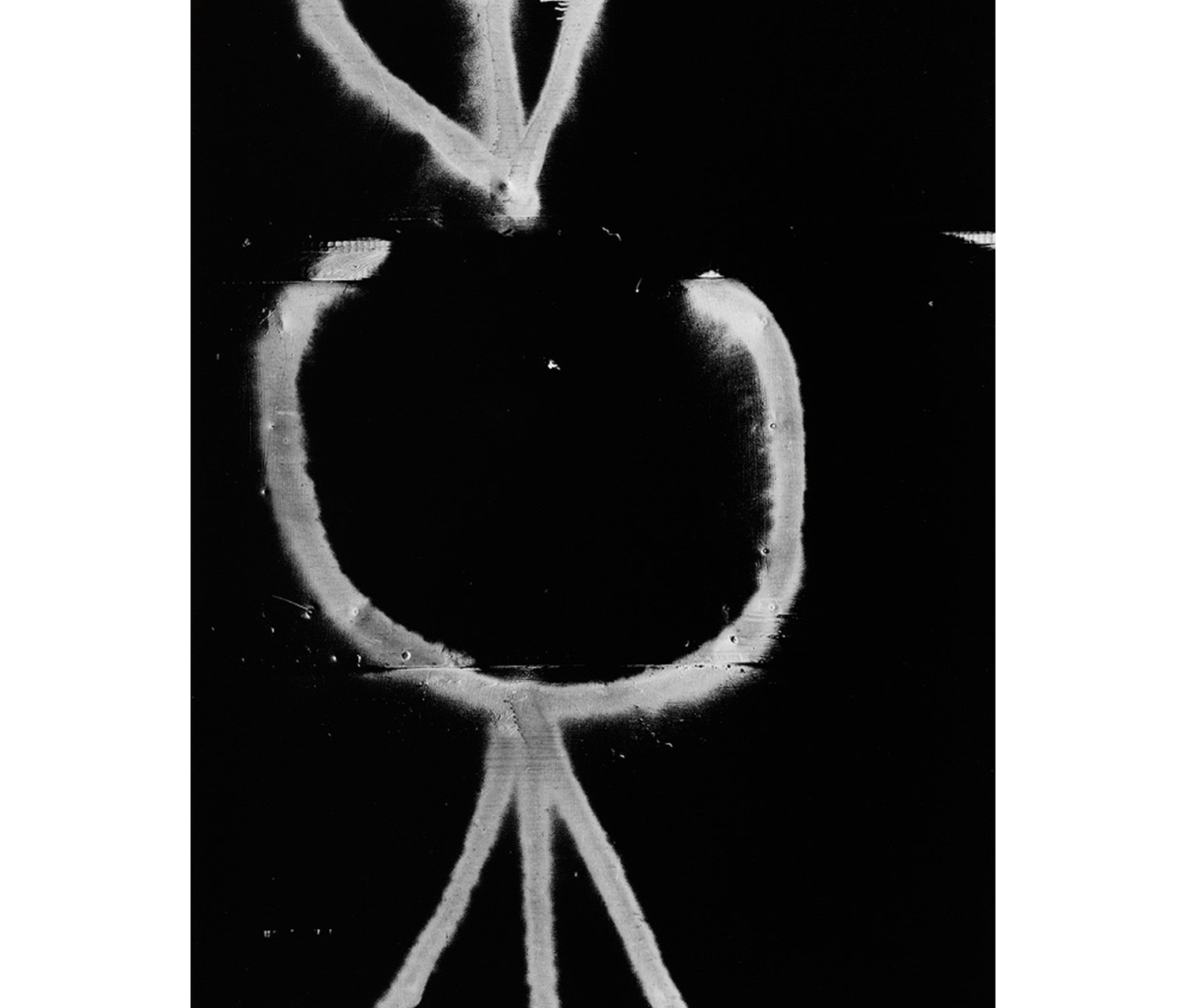

Moving into the 1940s, however, Siskind began experimenting with more abstract compositions. While other photographers looked past sidewalk markings, graffiti, and torn posters, Siskind considered them worthy subjects. He zoomed in tightly to create his desired composition, emphasizing the movement or texture that he found most compelling. In New York 1, small bolts indicate that the picture is of some sort of metal surface, perhaps a dumpster. But the focus is not on the larger object. Instead, Siskind positions a small section of graffiti marks slightly off-center, inviting the viewer to consider the asymmetrical lines, their white and gray tones, their contrast with the dark background, and what other markings they may be connected to.

Aaron Siskind. American, 1903–1991. New York 1, 1951. Gelatin silver print. Gift of Lynn Hecht Schafran, class of 1962. SC 2003.43.3.7.

With a strong emphasis on line and tone, Siskind’s work grew to closely resemble that of the Abstract Expressionist painters. He became close friends with artists such as Kline, Newman, and Mark Rothko. His relationship with Kline was so strong that after Kline’s death in 1962, he created several series of six photographs each titled “Homage to Franz Kline.” Organized by the location where they were taken, these groups emphasized the dark black lines and shapes that characterized most of Kline’s paintings.

In Lima 89 (Homage to Franz Kline), Siskind centers his picture on two black strokes that form an “L.” As in Kline’s painting Rose, Purple, and Black, the lines are imperfect and slanting, with stray brushstrokes visible. Though the black marks are the emphasis of the composition, he also pays considerable attention to the background. Larger blocks of paint, errant drippings, and the natural texture of the surface below all contribute to the composition, creating a backdrop that resembles the chaotic application of color in Kline’s work. While Kline and other painters were able to create their own composition, Siskind limited himself to what he found. Yet the way he framed his shots emphasized the smaller markings of an ordinary object, lending an entirely new and decidedly expressionist perspective.

Franz Kline. American, 1910–1962. Rose, Purple, and Black, 1958. Oil on canvas. Gift of Mrs. Sigmund W. Kunstadter (Maxine Weil, class of 1924). SC 1965.27.

Aaron Siskind. American, 1903–1991. Lima 89 (Homage to Franz Kline), 1975. Gelatin silver print. Gift of Lynn Hecht Schafran, class of 1962. SC 2003.43.3.8.

Though Abstract Expressionism continued to largely be associated with painting and drawing, Siskind was not the only abstract photographer during this time. He also developed a close relationship with photographer Harry Callahan, who also focused on more mundane subjects, taking pictures of leaves, grass strands buried in snow, or telephone wires spanning across the sky. Much like Siskind, Callahan preferred harsh black-and-white tones in his work, and often shot such a small fragment of his subject that it was unclear what the original object was. The composition of Grasses in Snow, Detroit is so tight that it is completely devoid of trees, fences, or any indicators of an outdoor scene. Without such context, the grasses appear more like ink or pencil marks more than blades of grass.

Harry Callahan. American, 1912–1999. Grasses in Snow, Detroit, 1943. Gelatin silver print. Purchased. SC 1977.29.4.

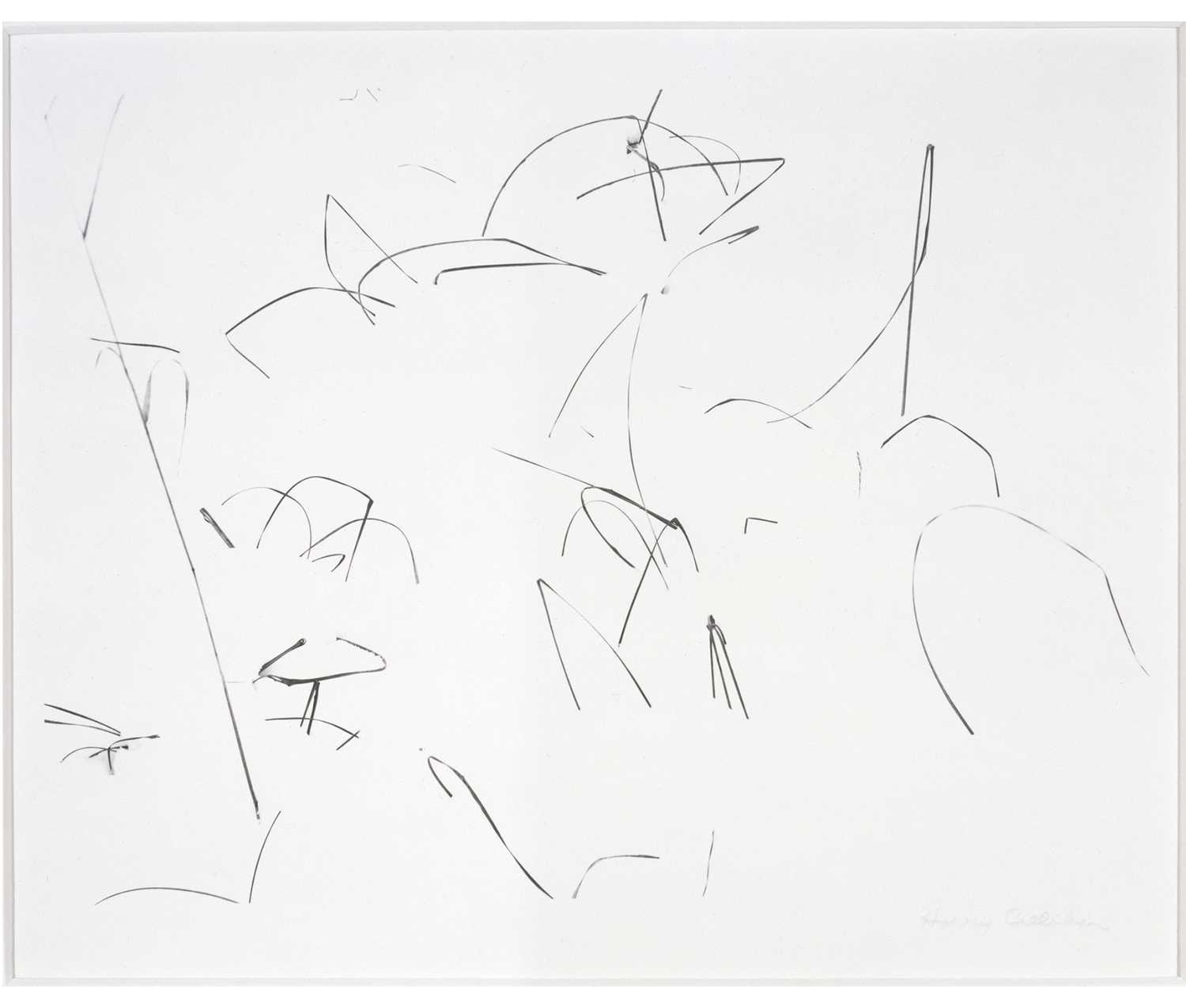

Aside from his own work, Siskind also was a prolific teacher. Together with Callahan, he founded a graduate program at the Illinois Institute of Technology and later taught at the Rhode Island School of Design. Many of his students, such as Joseph Jachna, below, continued in his abstract tradition, ensuring that what began as a movement for painting and drawing was now a space for photography as well.

Joseph D. Jachna. American. Colorado from Underware, 1975. Gelatin silver print. Gift of Nancy Waller Nadler, class of 1951. SC 2007.34.2.9.