Allegory

Guest blogger Saraphina Masters is a Smith College student, class of 2017, majoring in Classical Studies and Art History. She is the 2013-2015 STRIDE Scholar in the Cunningham Center for Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

Allegory is defined in the Encyclopedia Britannica as “a symbolic fictional narrative that conveys a meaning not explicitly set forth in the narrative.” In the visual arts, allegory can be used to add additional layers of meaning to the existing depiction.

Allegory in art can range broadly in terms of complexity, meaning, and appearance. It can be simply executed, such as the use of colors that are associated with particular emotions (for example: black to signify death or grief). Equally, allegory can be incredibly complicated, with an artist depicting an entire scene full of subtle details that the viewer must decipher individually and then combine to read the greater meaning. Allegory relies heavily on the observers’ interpretations of the meaning that is being set forth. An artist may depict a dove perched in a tree in the background of a work and depend upon the viewer to notice it and associate it with its colloquial meaning of peace. A picture may seem to be about one particular subject, but when an allegorical detail is made clear, the whole meaning can change or be enhanced.

Elihu Vedder. American, 1836–1923. Sorrow, n.d. Crayon and chalk drawing on two layered sheets of gray wove paper. Gift of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1955.12.

For example, Sorrow, a drawing by the American artist Elihu Vedder (above), shows a sad looking woman with her face framed by a wreath of leaves. From both the title and the appearance, it is clear that there is a theme of grief here. However this theory can be supported by the allegorical meaning of the plant, which appears to be acanthus leaves. Acanthus leaves were very common in the Greco-Roman artistic tradition and symbolically represent enduring life. Moreover, they were often present at funerals. Thus, knowledge of the type of plant, which makes up a frame that might too quickly be dismissed, can in fact make the meaning of the work of art clearer or more powerful.

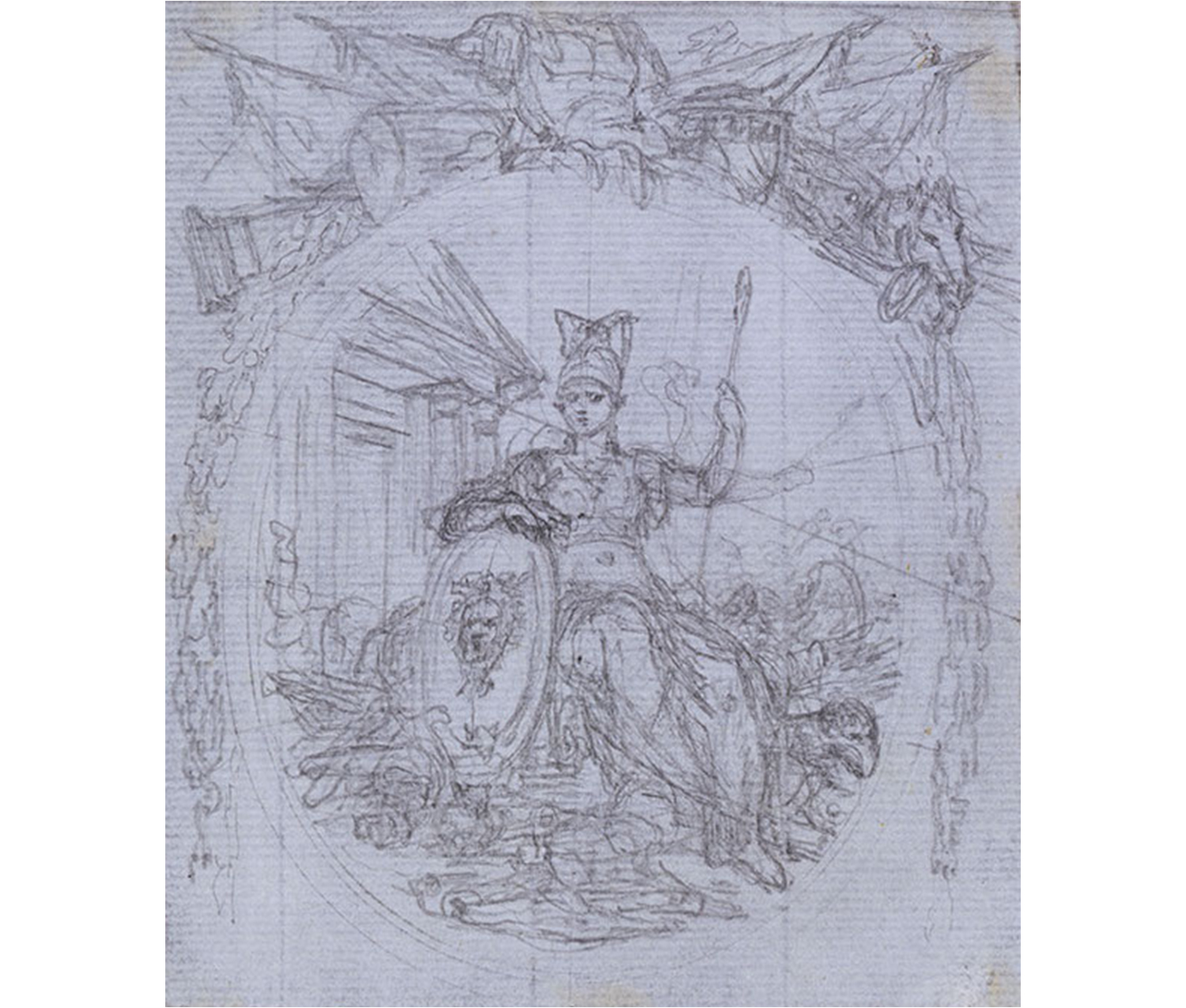

Hubert François Bourguignon Gravelot. French, 1699–1773. Allegorical Figure for a Title Page, n.d. Black chalk on off white antique laid paper. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1969.58.8.

Ancient Greece is one particular origin point for the allegorical tradition. The ancient Greek society had a fascinating proclivity for assigning corporeal forms and personalities to abstract concepts. They used figures to represent a massive range of subjects, from emotional and political concepts to phases of life and even celestial events. A few examples of this are the allegorical figures of Democracy, Poverty, Love, Rumor, Youth, Fear, and many more. Once these ideas were given human shape, they could then be active participants in mythological stories as well as be depicted in art. This tradition carried over into the Roman world. The Romans, like the Greeks, depicted many of the same concepts as well as new ones. A common allegorical figure was Rome herself. Usually called Roma and always portrayed as a woman, she was the entirety of the city encapsulated into one figure. This was an artistically and politically useful tool, as the use of allegory makes a large or intangible concept much more understandable and accessible for the viewer. This increased appreciation of art and even loyalty to a place and society. This custom extended many places conquered by the Romans and gave birth to the allegory of Britannia, the personification of Britain during the time of her Roman occupation.

Chinese. Allegory of Painting, ca. 1800–1825. Oil on glass. Gift of Dorothy Spring, Class of 1918. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1970.20.2.

In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, the Christian tradition took over and rather than representing deified aspect of pagan life, artists used allegorical representations of high moral concepts and religious virtues. Faith, Hope, Justice, Temperance, and more were all depicted as human forms. During the same time period, secular art also made use of allegorical figures. The Seven Liberal Arts were often represented as individuals. Grammar, Logic, Rhetoric, Geometry, Arithmetic, Astronomy, and Music were frequently depicted in art as scholarly people. They were often accompanied with signal accessories that hinted to their identity. Geometry or Arithmetic may hold a pen or stylus with which they will solve math problems, Grammar most likely has books nearby, and Music consistently has an instrument at hand. Above you can see an allegorical painting of the personification of Painting herself. A relatively obvious example of allegory, you can see the creation of a painting, as well as a paintbrush and the female figure holding a pot of paint.

Johann Gottlieb Prestel. German, 1739–1808. Possibly by Katharina Prestel. German, 1747–1794. Truth Attacking Envy, 1781. Chiaroscuro woodcut with gold leaf on paper. Purchased with the Hillyer-Mather-Tryon Fund. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1991.19.

The woodcut above features more abstract example of allegory. A female figure assaulting a male figure does not immediately lend itself to easy identification. However, the viewer can dissect the image by looking for meaning in different aspect of it. Firstly, the figures are on a cloud in a heavenly environment. This may mean that the theme is related to high morality or mental concepts. Secondly, there is clearly a theme of conflict and opposition between the two concepts these figures are meant to embody. The female figure is positioned higher than the male, with her arm raised in a strong and imposing gesture. This may indicate that she is the morally superior figure and the ugly, suffering male figure she is suppressing is likely a vice or sin. The title of the print, Truth Attacking Envy, supports these inferences made from the image’s allegorical markers. Interpreting allegory in art is something akin to detective work; requiring attention to detail, fact-based hypothesizing, and a healthy dose of curiosity.