Animal Locomotion

Guest blogger Maggie Hoot is a Smith College student, class of 2016, with a major in Art History. She is a Student Assistant in the Cunningham Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

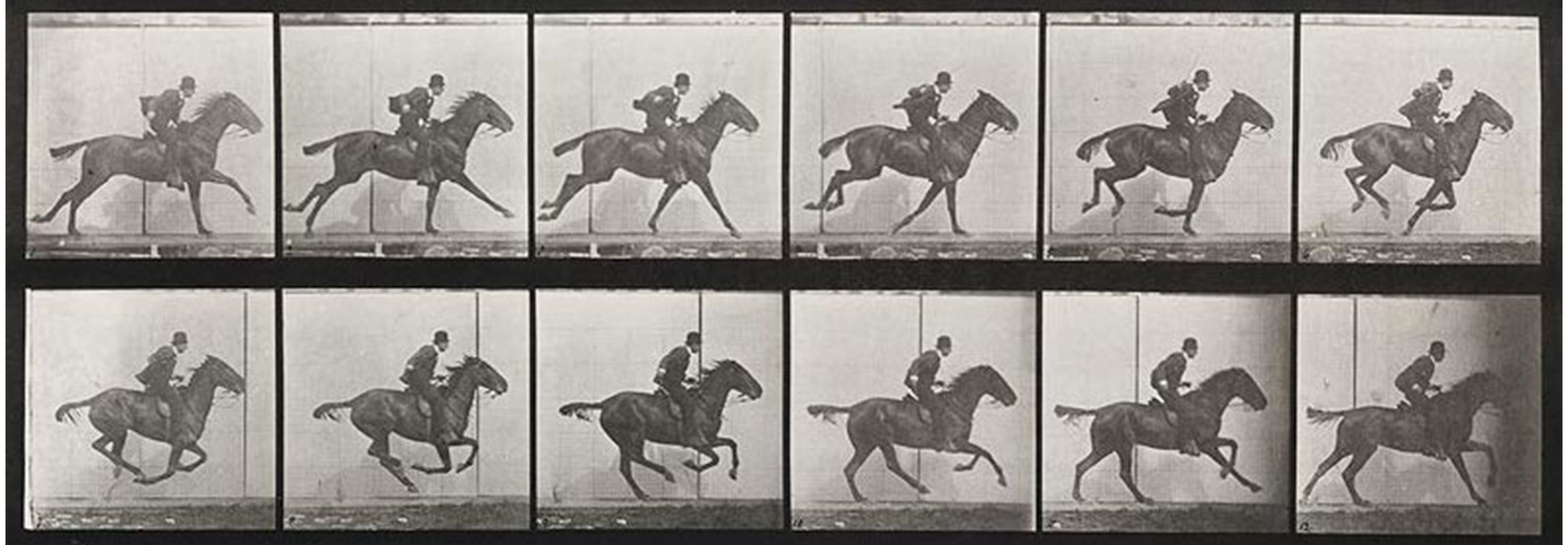

In 1872, former California governor, railroad tycoon, and subsequent college founder, Leland Stanford wanted to prove the hotly debated hypothesis that there was a point in a running horse’s gait when all four feet would be off the ground at once. He hired a locally famous British photographer named Eadweard Muybridge to test the hypothesis by photographing his horse, Occident, in motion. At this time, photographic technology was not advanced enough and consequently Muybridge could not capture a definitive image.

Five years later, Muybridge returned to Stanford’s ranch with improved equipment to try again. He was finally able to take a clear series of photos and proved Stanford right. This set of photographs of Stanford’s horse, Sallie Gardner, became an instant sensation and Muybridge’s photographic career reached new heights. Muybridge spent the next seven years touring the US and Europeshowing his photographs and lecturing on both photographic technologies and new research related to animal locomotion. He presented his work on a zoopraxiscope, the first machine capable of large-scale projection, which Muybridge himself invented. Muybridge based his invention on a children’s toy, the zoetrope, a handheld spinning drum that produces the illusion of motion, and used a lantern to project the image onto a screen.

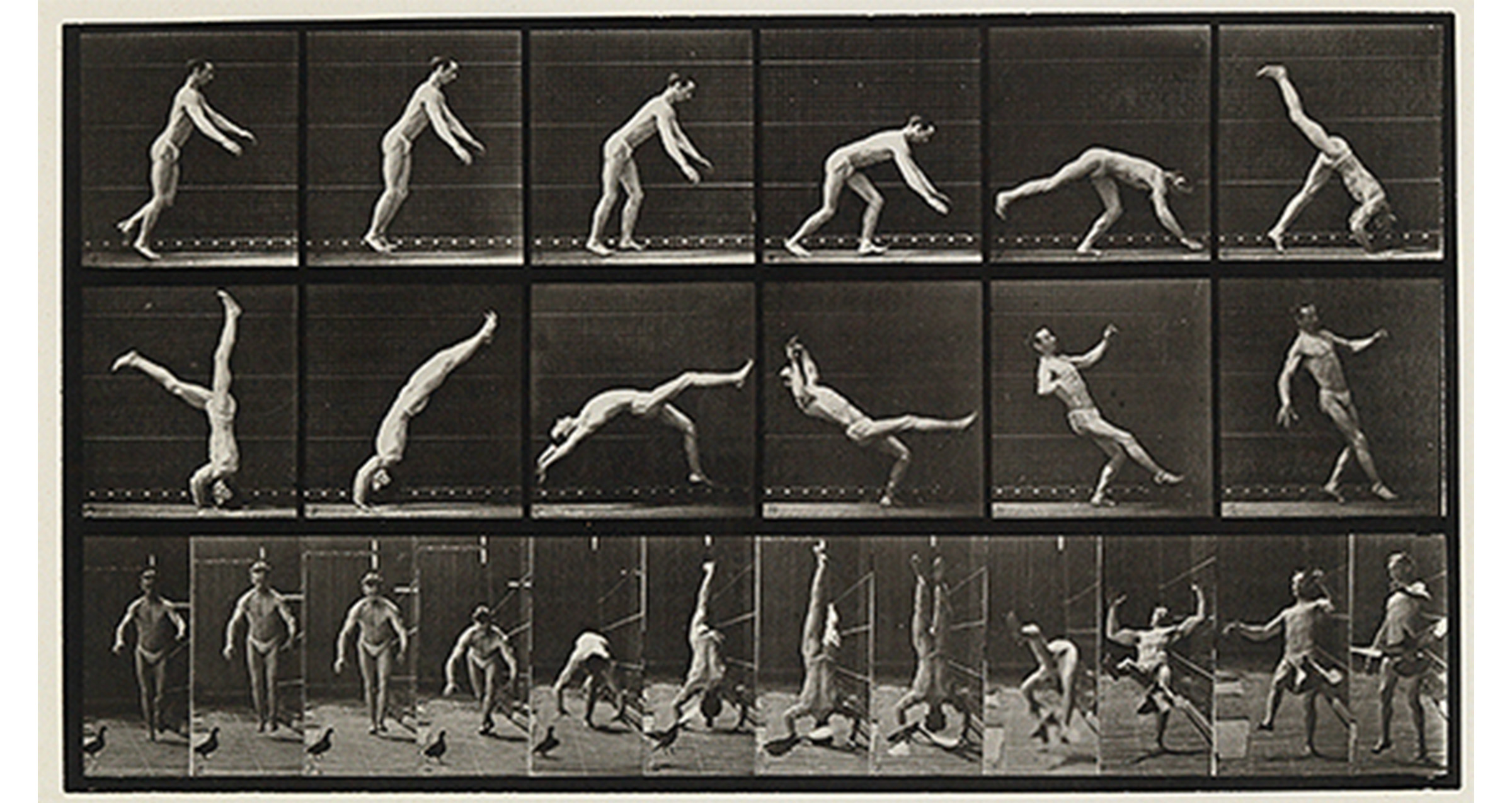

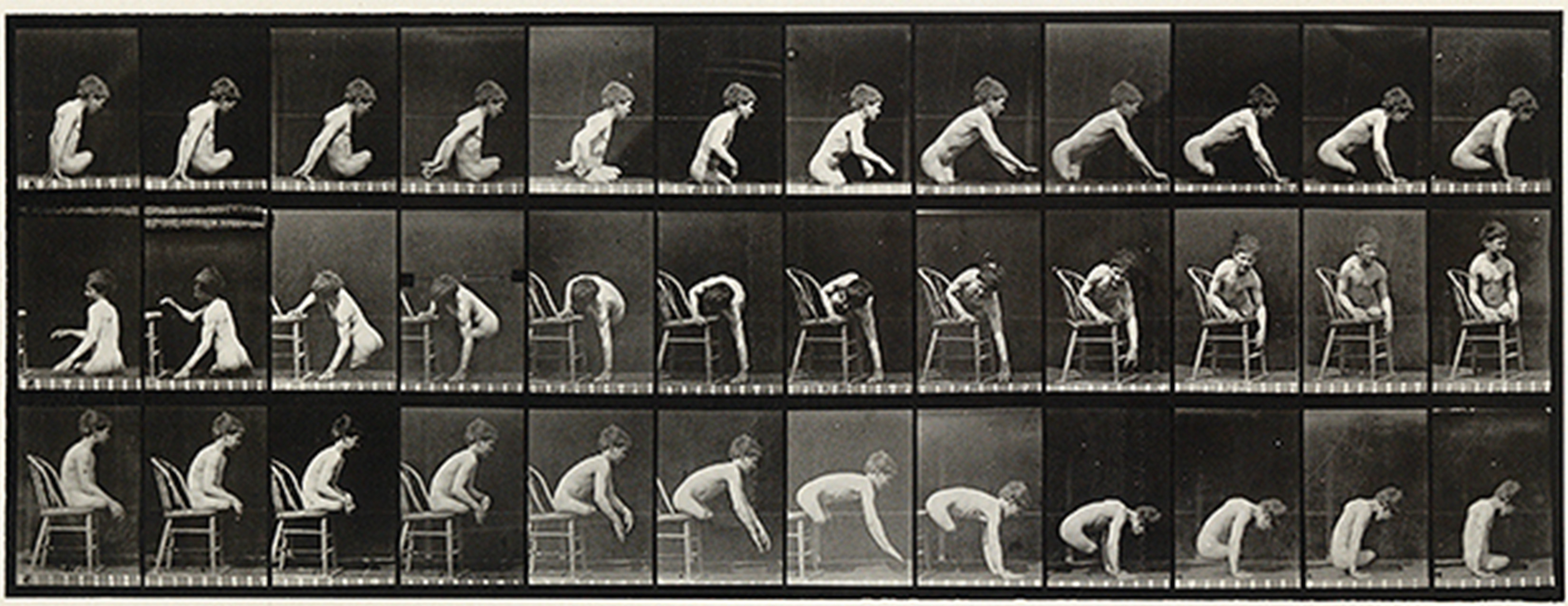

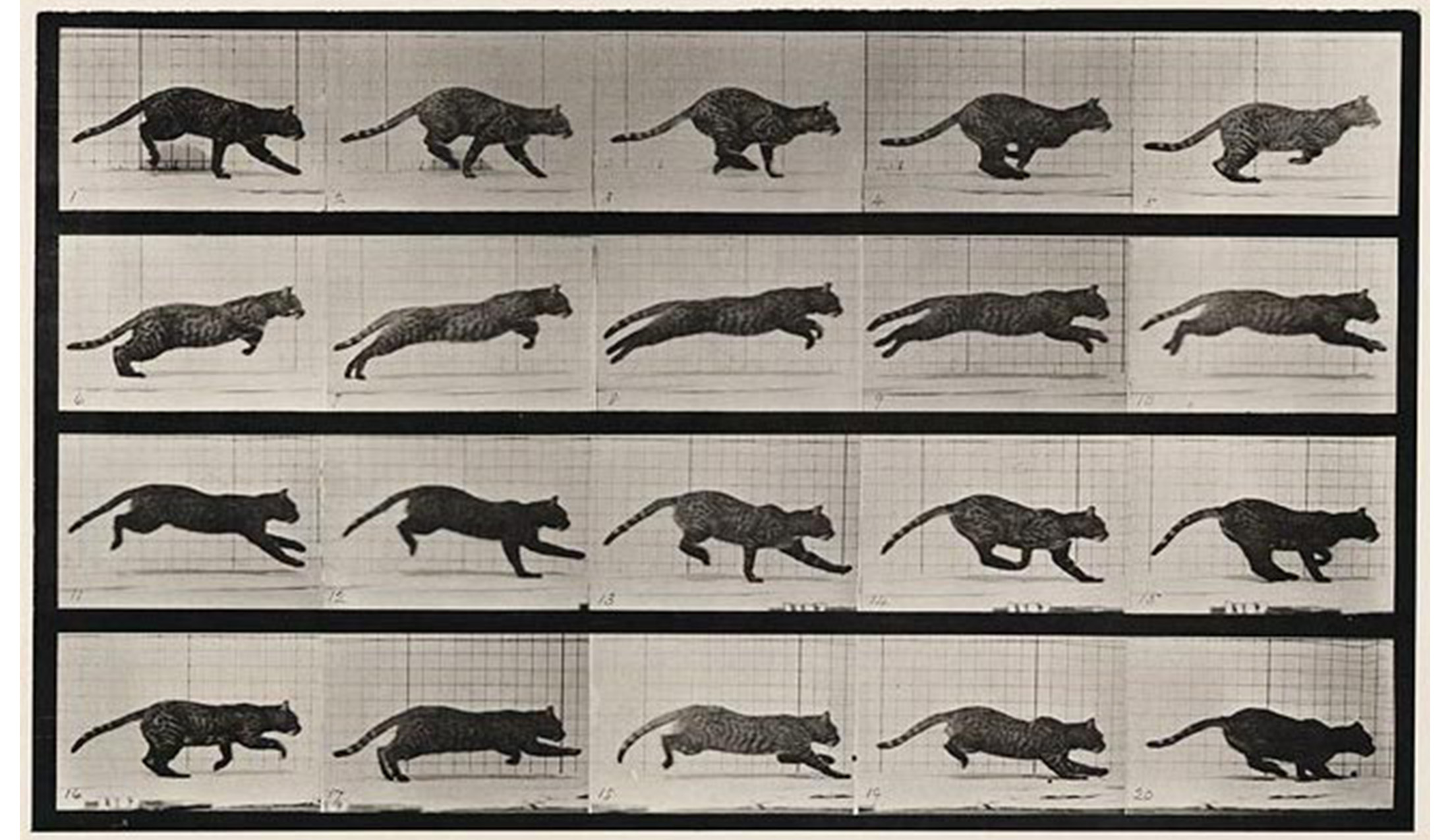

In 1884, Muybridge took a job at the University of Pennsylvania and began a new project based on his work for Stanford, but expanded his subjects well beyond horses. Muybridge photographed “men, women, and children, animals and birds, all actively engaged in walking, galloping, flying, working, playing, fighting, dancing, or other actions incidental to every-day life," (Animal LocomotionProspectus, 1887). He used models, athletes from the university, disabled patients from the local hospital, and animals from the Philadelphia Zoo. Three years later, he published his eleven volume masterpiece Animal Locomotion, which contains 781 plates with 20,000 total photographs. The SCMA has 516 different plates from Animal Locomotionin its collection.

Eadweard Muybridge. English, 1830–1904. Animal Locomotion: Plate 365, 1887. Photogravure on paper mounted on paperboard. Gift of the Philadelphia Commercial Museum. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1950.53.365.

Eadweard Muybridge. English, 1830–1904. Animal Locomotion: Plate 538, 1887. Photogravure on paper mounted on paperboard. Gift of the Philadelphia Commercial Museum. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1950.53.538.

Muybridge’s work revolutionized the way scientists studied locomotion and physiology. Previously, scientists were largely limited by what they could observe with their own eyes, especially concerning objects in motion. Before Muybridge took his photographs, there was no way to prove Stanford’s hypothesis. Muybridge’s photographs helped generate new perspectives on the musculature and movements of people and animals.

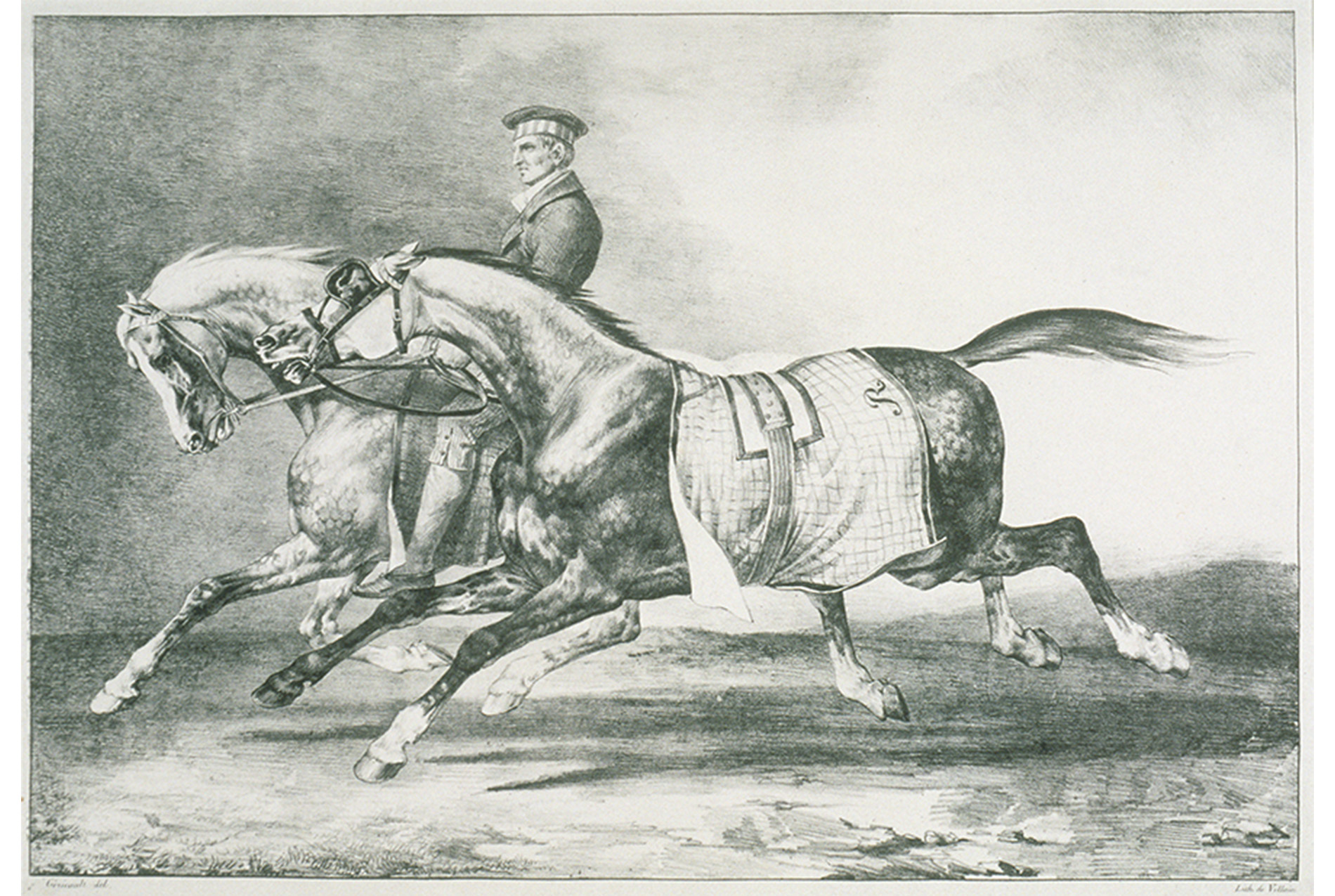

Though the impact of Muybridge’s work was considered to be primarily scientific, there was a less obvious but equally important impact on the artistic world. Many artists, including Edgar Degas, began copying poses from Muybridge’s photos to ensure accuracy in their own work. Before Muybridge, artists commonly drew horses running with both forelegs extended equally forward and hind legs equally behind, as in the Géricault print pictured below, which looks more like a cat leaping. Though most artists embraced the new technology and the accuracy it afforded, others such as August Rodin thought that it simply widened the gap between art and science. In his view, Muybridge’s work, and photography in general, fell on the side of science because it stopped time unnaturally, while art was the synthesis of more than a single moment.

Théodore Géricault and Eugene Louis Lami. French. Gericault: 1791–1824; Lami: 1800–1890. Two Dapple-Gray Horses Being Taken for a Walk, 1822. Lithograph on chine collé on paper. Gift of Frederick H. Schab. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1973.33.

Eadweard Muybridge. English, 1830–1904. Animal Locomotion: Plate 719, 1887. Photogravure on paper mounted on paperboard. Gift of the Philadelphia Commercial Museum. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1950.53.719.

Muybridge considered himself first and foremost, an artist. This was clearly demonstrated in his habit of adding or subtracting photographs in a series to create more aesthetically pleasing results. Though he buried all the negatives, some collotypes remain today that indicate changes made before the final printing (for examples and more information, please visit the National Museum of American History website: https://americanhistory.si.edu/muybridge/index.htm). Despite his alterations, Muybridge’s work revolutionized the way the world understood the movement of animals and is still an important resource for the study of the body in motion.