Of Birds and Fourteen Year Olds

Maggie Kurkoski is a member of the Smith College class of 2012 and the Brown Post-Baccalaureate Curatorial Fellow in the Cunningham Center.

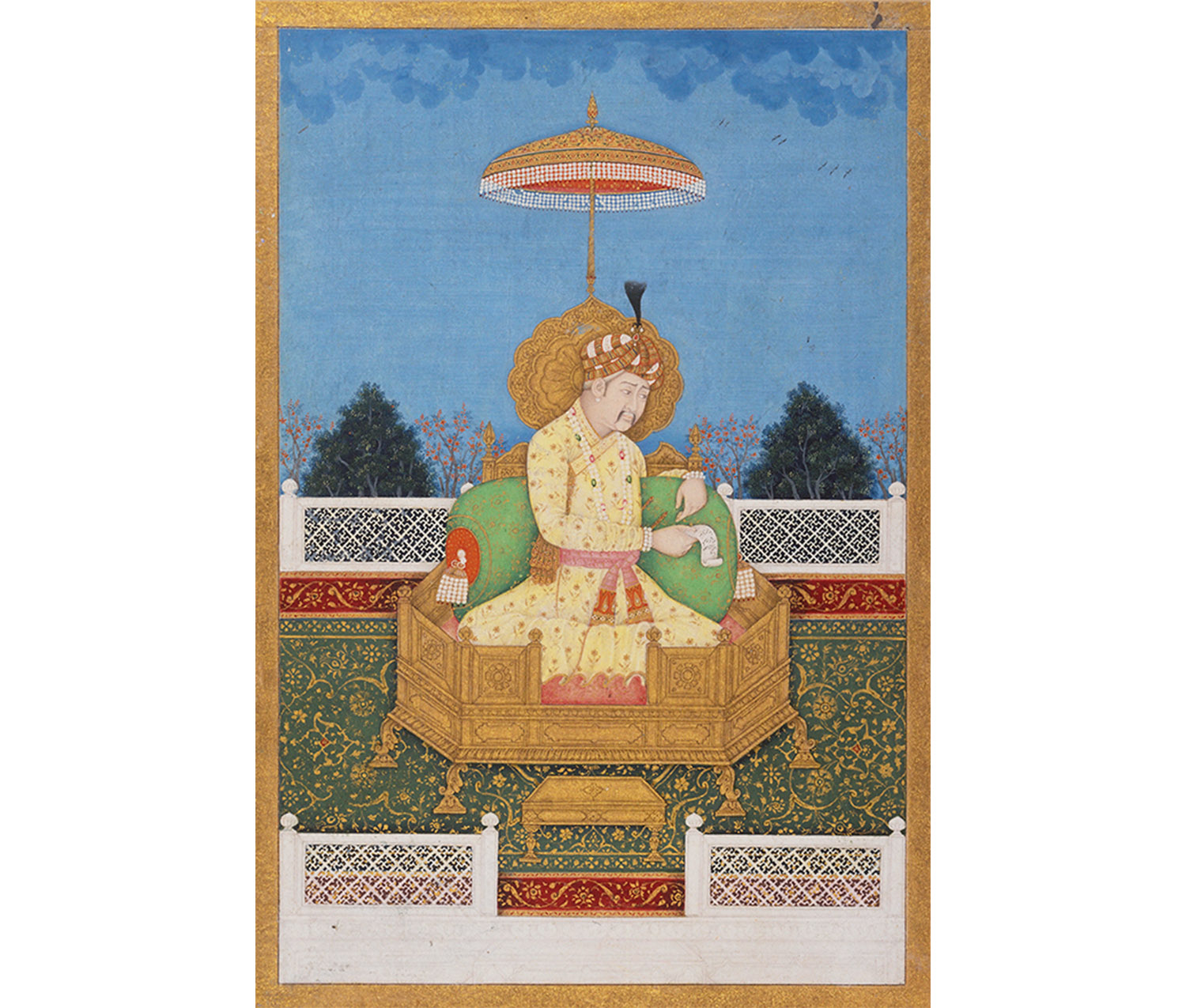

The tradition of Mughal miniatures first appeared in South Asia in the mid-16th century, under the patronage of Emperor Akbar. In the spirit of cultural tolerance, this Muslim ruler commissioned his court artists to produce manuscripts illustrating Hindu epics, historical narratives and personal biographies; these works blended the local Jain manuscript tradition with Safavid (Persian) miniatures. The result was opulent, precise, rich in color and in detail. We have some examples in the Smith Museum collection, such as this portrait of Emperor Akbar painted after his death.

Unknown artist. Mughal Emperor Akbar (reigned 1556-1605), mid 17th century. Opaque water base colors and gold on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John Kenneth Galbraith (Catherine Atwater, class of 1934). Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1981.27.9.

This rich tradition still lives on, although only a few practice it. Nusra Latif Qureshi is a leading figure in the contemporary miniature scene, having studied the art at the National College of Arts in Lahore, Pakistan.

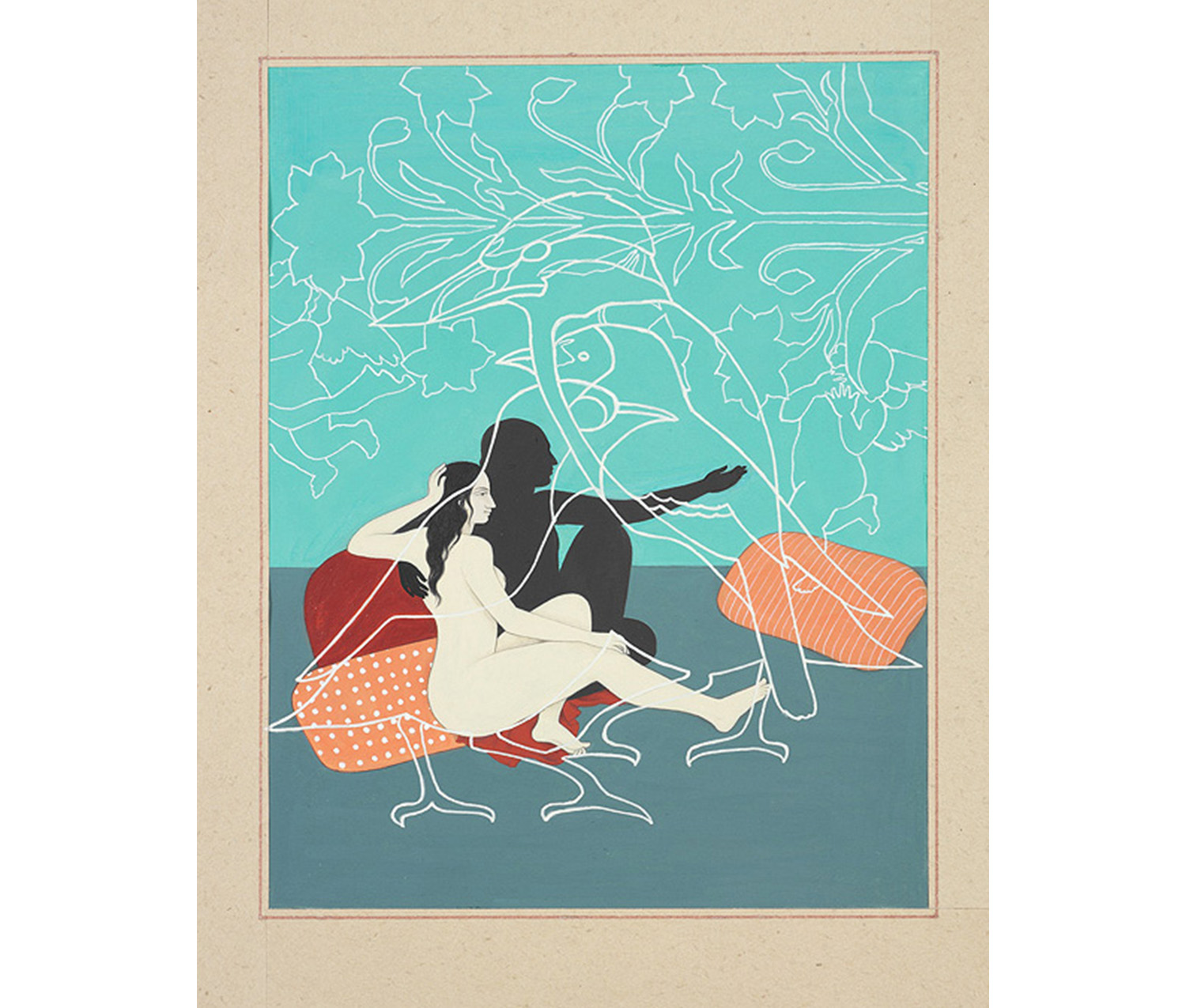

Three Songs of Desire reveals Qureshi’s mastery of the miniature style, in the beautifully rendered figure of a woman. The colors are as deep and saturated as the portrait of Emperor Akbar. She even painted the work on wasli, the delicate handmade paper created for traditional miniatures.

Nusra Latif Qureshi. Pakistani, b. 1973. Three Songs of Devotion, 2002. Gouache on wasli paper with tan-colored paper frame. Purchased with the Janice Carlson Oresman, class of 1955, Fund. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2004.5.

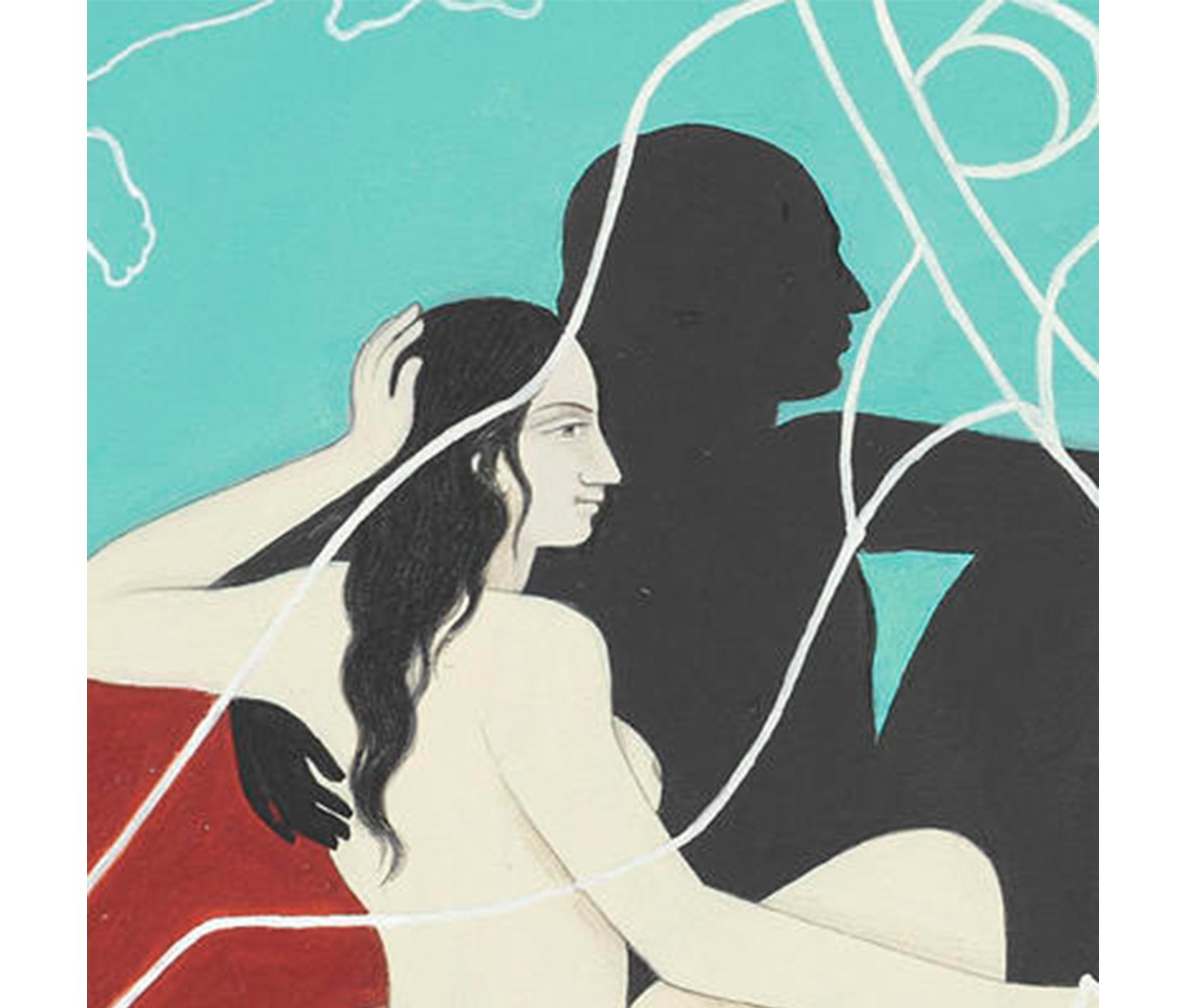

That said, her work is decidedly untraditional. As a woman engaging with an art form dominated by men, she plays with those images and motifs gone unquestioned in miniature art for centuries. Often, she draws focus back to female figures in her work, something you can see clearly in Three Songs of Devotion. The man and woman embrace, a typical romantic intimacy, but the man is blotted out in black, a silhouette. All detail and individualism belongs to the woman, who sits straight and barely supported by her lover.

Detail of couple from Three Songs of Devotion

In this piece, Qureshi has also stripped out the typical opulence of a Mughal miniature, and replaced that environment with flat plains of color. Layered above the main scene are lines of white, forming new images entirely.

Detail of birds from Three Songs of Devotion

These untraditional additions actually have their basis in a different era of Indian art. Starting in the late 18th century, the British East India Company began to expand further into South Asia, and with it came an influx of British employees. With this migration was a demand for art that recorded these unfamiliar settings and Indian artists were hired to paint local monuments, flora and fauna. Watercolor was the medium of choice, as this type of paint is quick to dry, and easy to carry around. Eventually, Indian artists began to produce these works in large numbers to sell as souvenirs to foreign travelers.

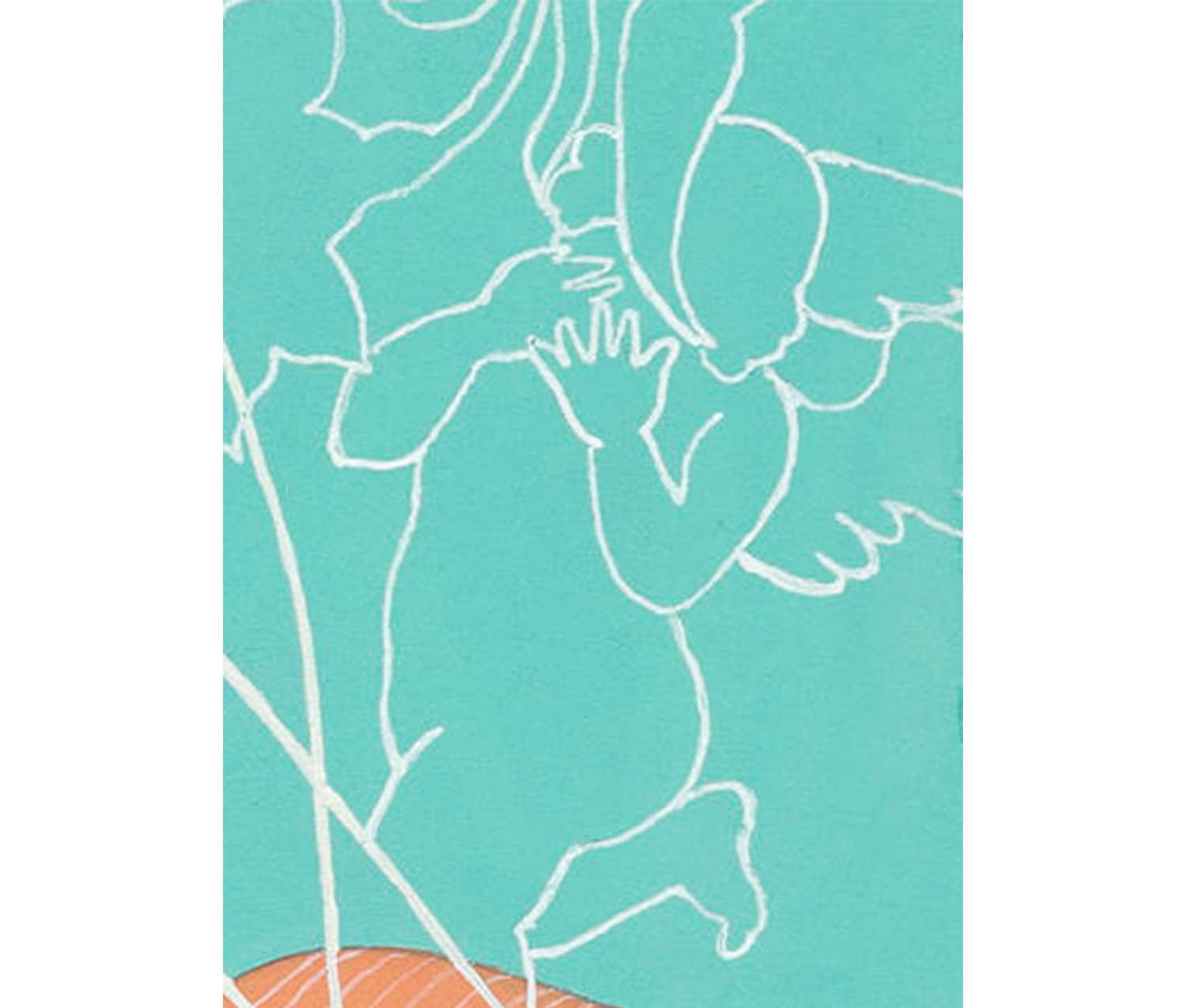

Detail of a putto (cupid) from Three Songs of Devotion

The style became known as ‘Company painting,’ and these realistic, detailed watercolors have their echoes in Qureshi's works. In Three Songs of Devotion, ghostly white outlines form birds that overlap each other and the larger image, flanked by the winged putti (or cupids) so often seen in European Renaissance art.

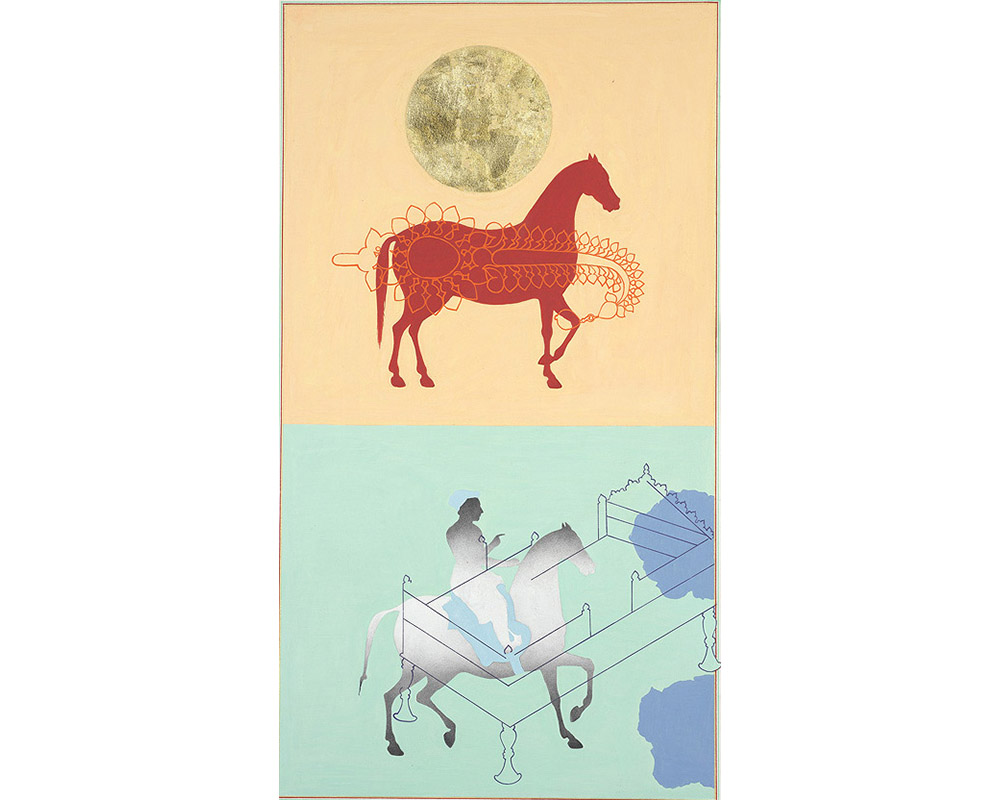

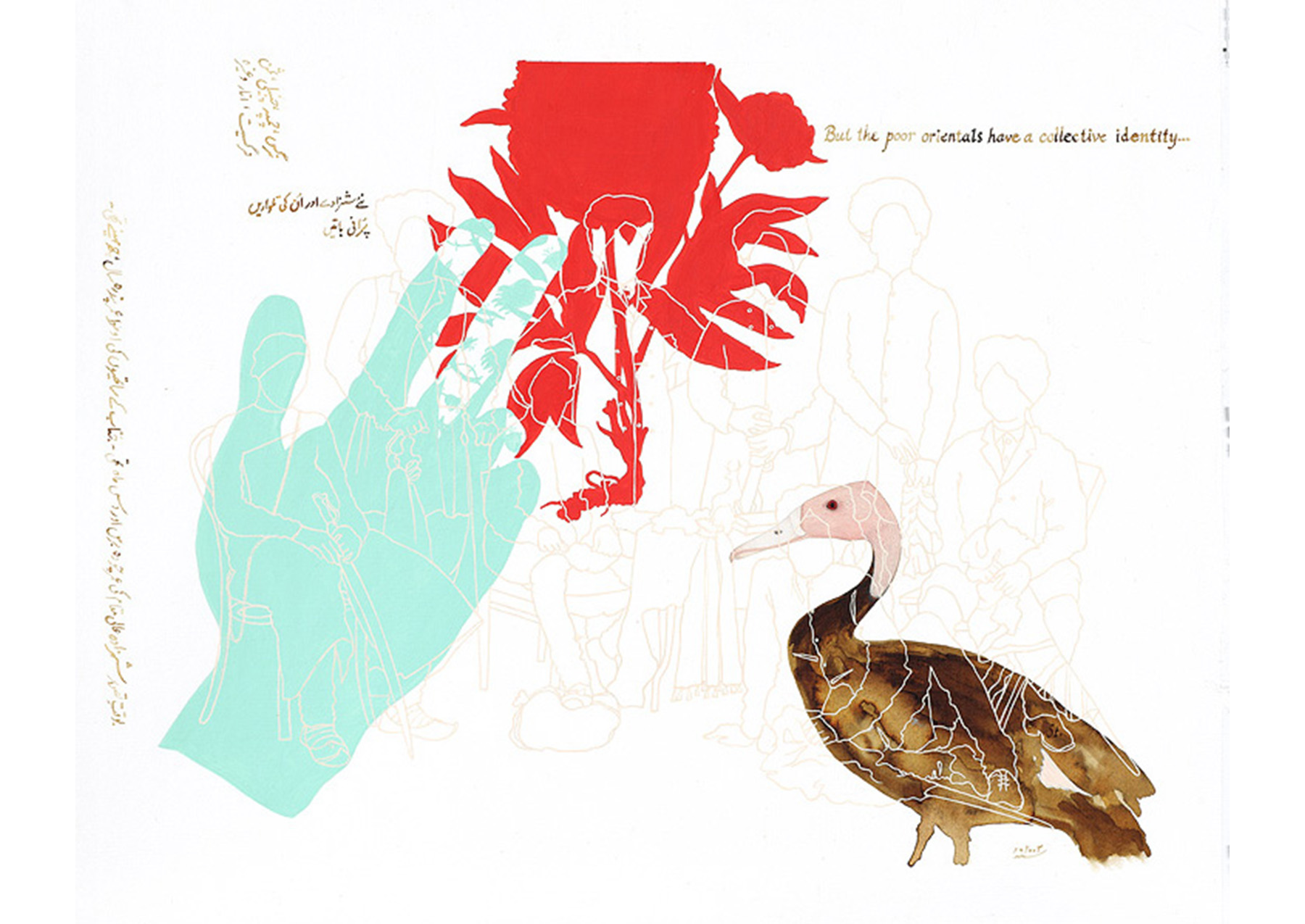

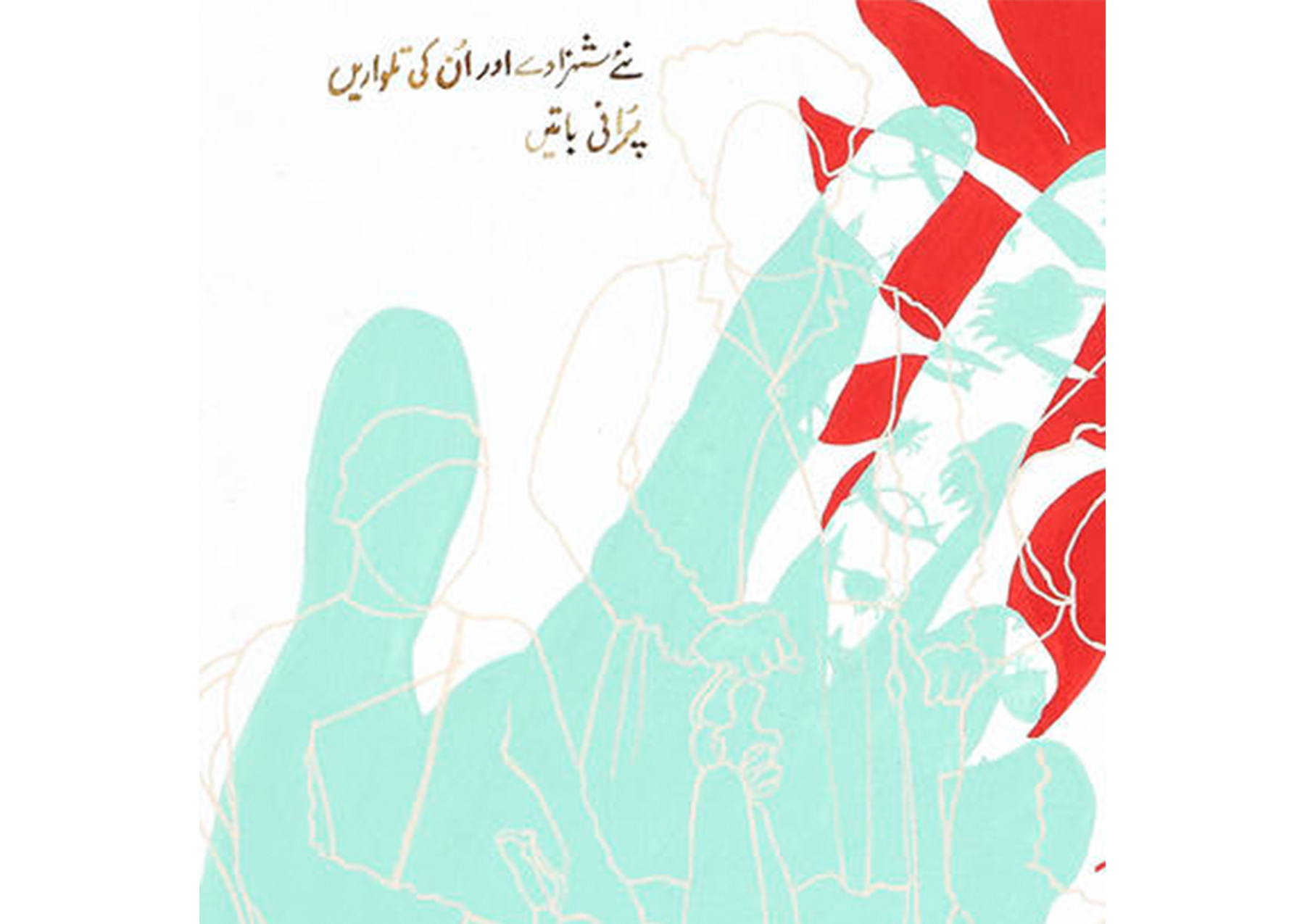

Nusra Latif Qureshi. Pakistani, b. 1973. Of Birds and Fourteen Year Olds, November 2003. Gouache and ink on paperboard. Purchased with the Richard and Rebecca Evans (Rebecca Morris, class of 1932) Foundation Fund. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2004.6.

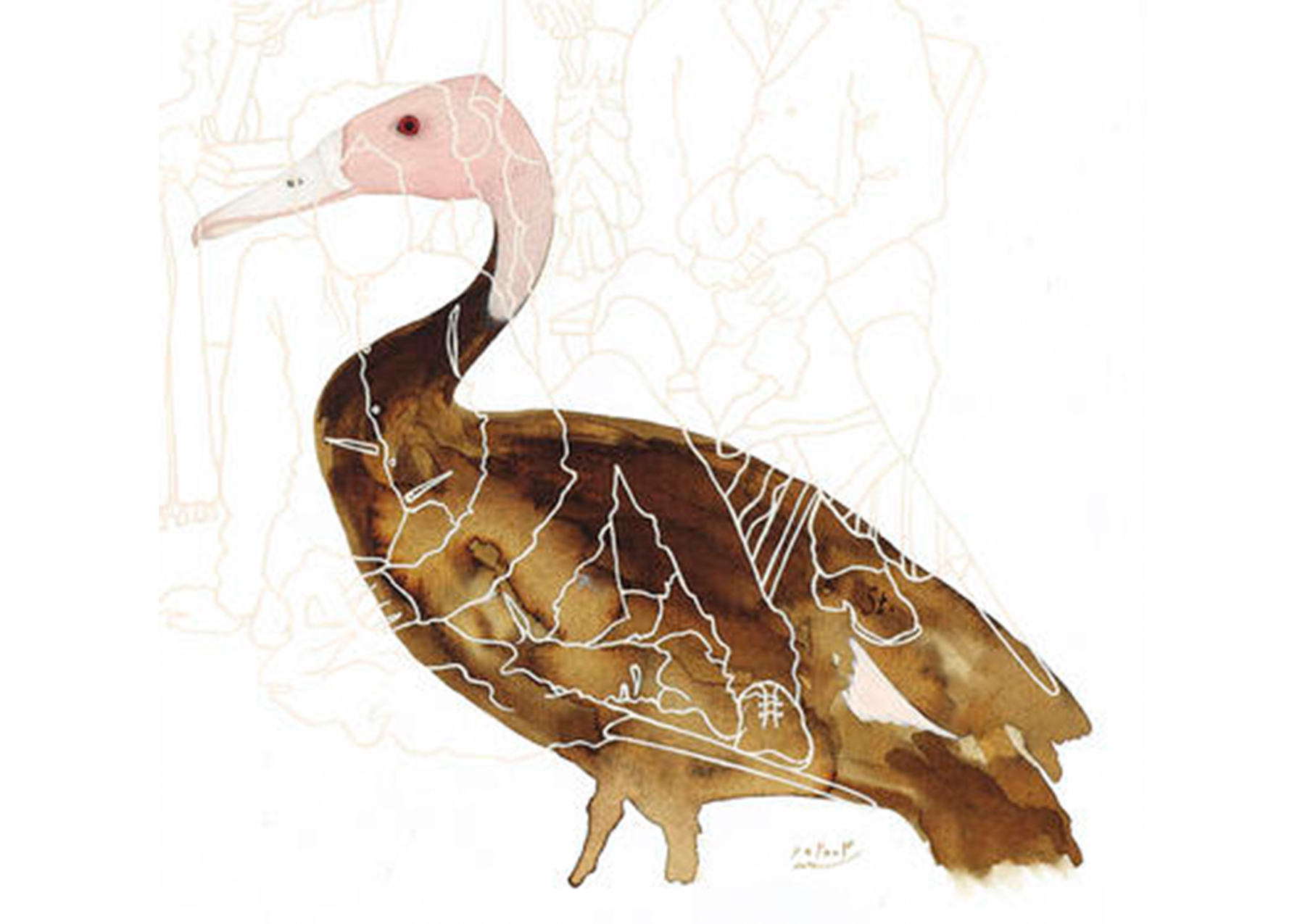

Qureshi's drawing Of Birds and Fourteen Year Olds likewise references these Company paintings; she even renders a crane’s body with watery brushstrokes, reminiscent of the preferred medium for these early ornithological souvenirs.

Detail of bird in Of Birds and Fourteen Year Olds

A major part in Of Birds and Fourteen Year Olds is the ghostly outline of a group sitting and standing together, posed for a photograph. Qureshi has taken what seems to be a colonialist photograph from the early 20th century and recreated it here, although she has omitted many details.

Detail from Of Birds and Fourteen Year Olds

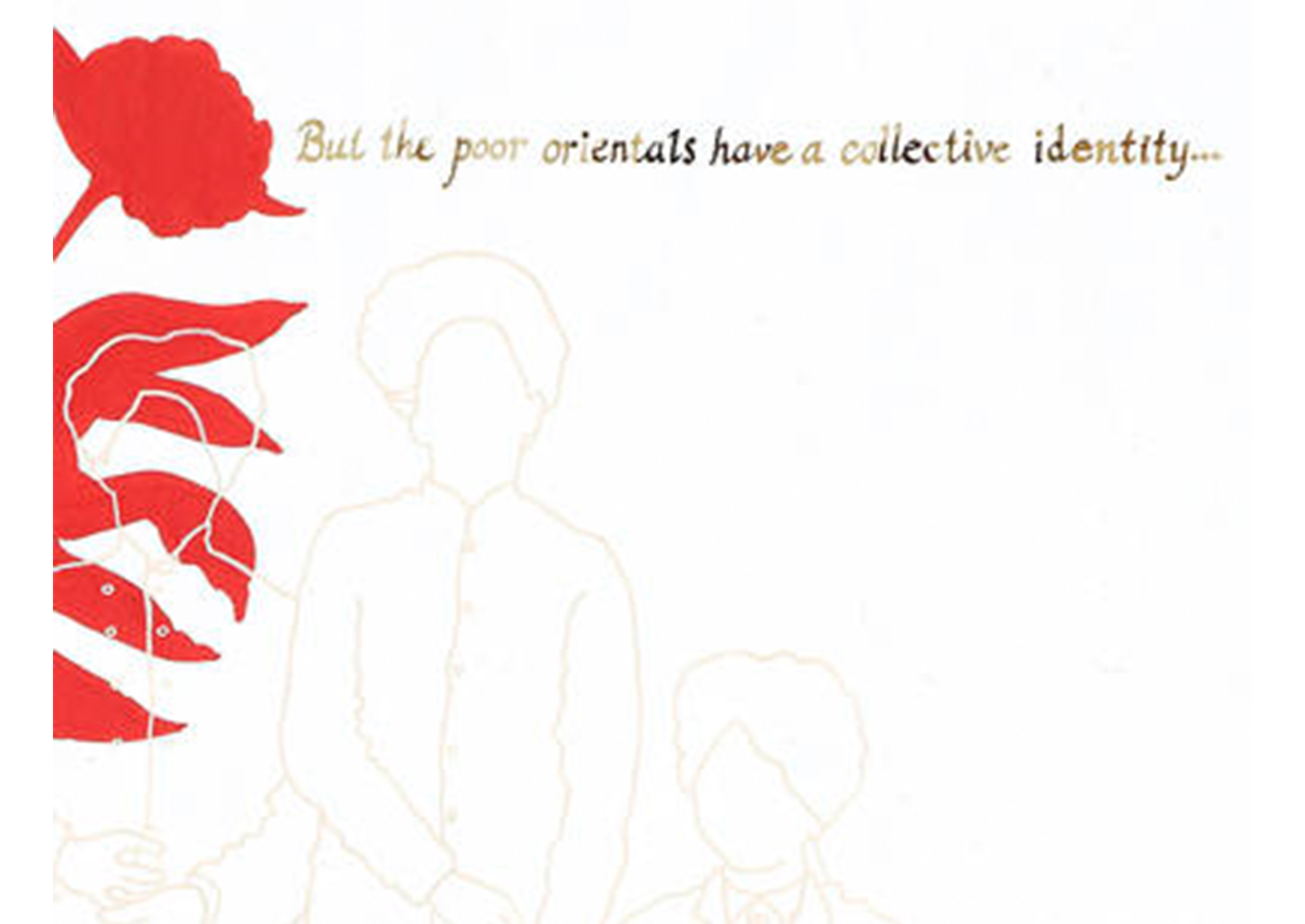

The light color makes the figures difficult to see against the white background. I wonder if they are the fourteen-year-olds referenced in the title, but I can’t tell from the image alone. Indeed, they are faceless, their identity obscured, an omission made more powerful by the text floating above them: “But the poor orientals have a collective identity…”

Detail from Of Birds and Fourteen Year Olds

Qureshi is telling a story of erasure, both present and past. Her art speaks to a history some would prefer to forget, and racist attitudes that still pervade.

There are purists who prefer the unadulterated miniature style. In her own way, however, Nusra Latif Qureshi carries on the spirit of experimentation foraged in the artists’ studio of Emperor Akbar, creating a hybrid art that weds the complex cultural interactions that still influence South Asia today.