Books of Hours

Colleen McDermott is the Brown Post-Baccalaureate Curatorial Fellow in the Cunningham Center.

The Book of Hours was a type of Christian prayer text that was extremely common in the Middle Ages. Unlike most of the religious writing being produced during this time, they were intended for private, individual devotion, meant to imitate the structure of monastic hours in a format more easily accessible to lay folk. They could be lavishly illustrated or left unadorned, depending on how wealthy the owner was.

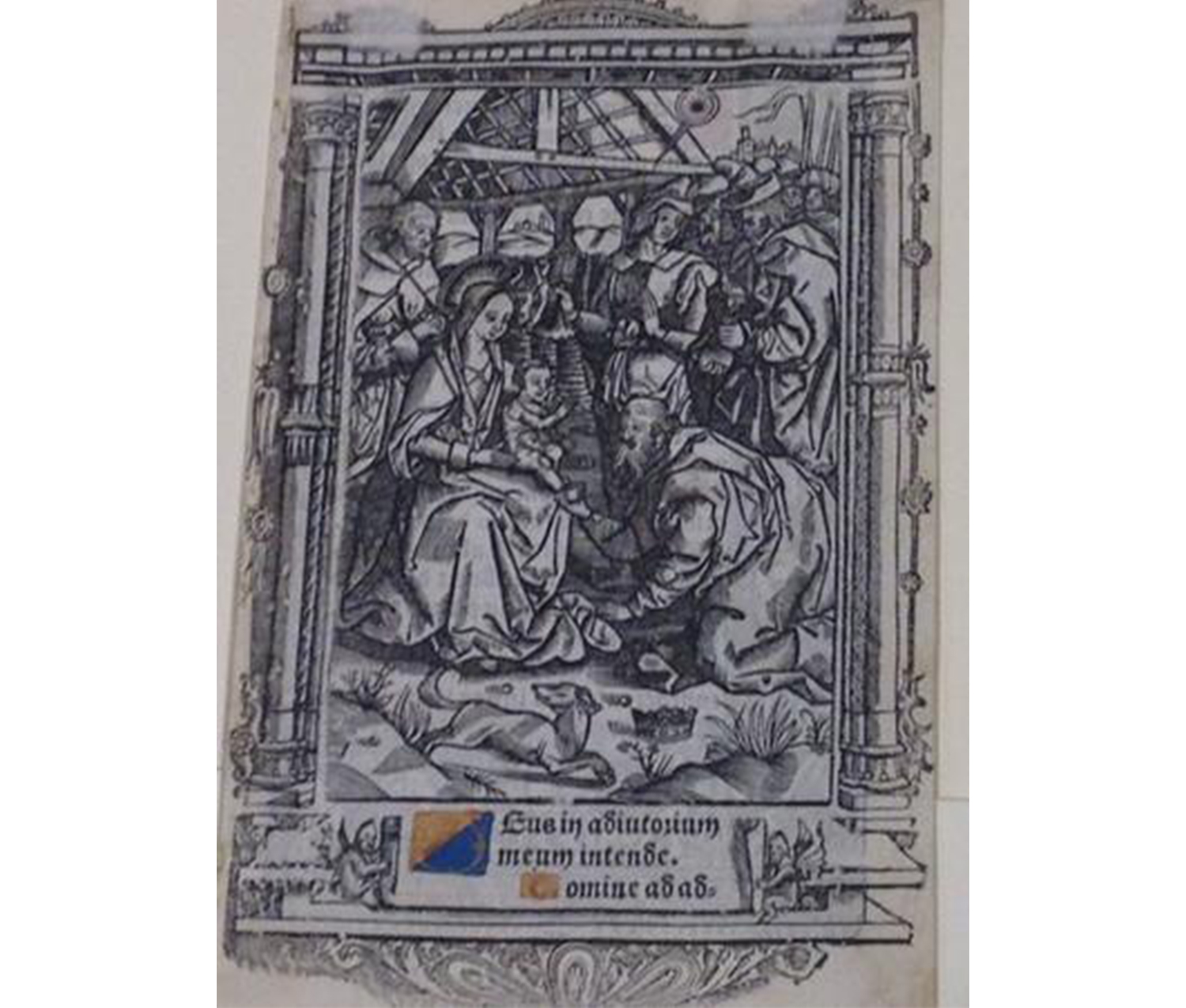

Unknown. French. Manuscript Leaf with Adoration of the Magi, from a Book of Hours, 15th century. Tempera, ink, and gold on vellum. Gift of the estate of Mrs. Charles Lincoln Taylor (Margaret Rand Goldthwait, class of 1921). Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1994.20.19.

The above example would have been taken from a finer edition; the illustration depicts the Adoration of the Magi, wherein three kings pay their respects to Mary and the infant Jesus. While some of the background details are crude, the figures themselves are well-made.

The kings in particular are lavishly dressed—though their style is certainly more in accordance with medieval fashion than biblical. The crowns, halos, and many of the details on the hair and clothing have been highlighted in shell gold, a kind of paint made by crushing gold leaf in a mixture of water and adhesive. This gives it a wonderfully luminescent quality.

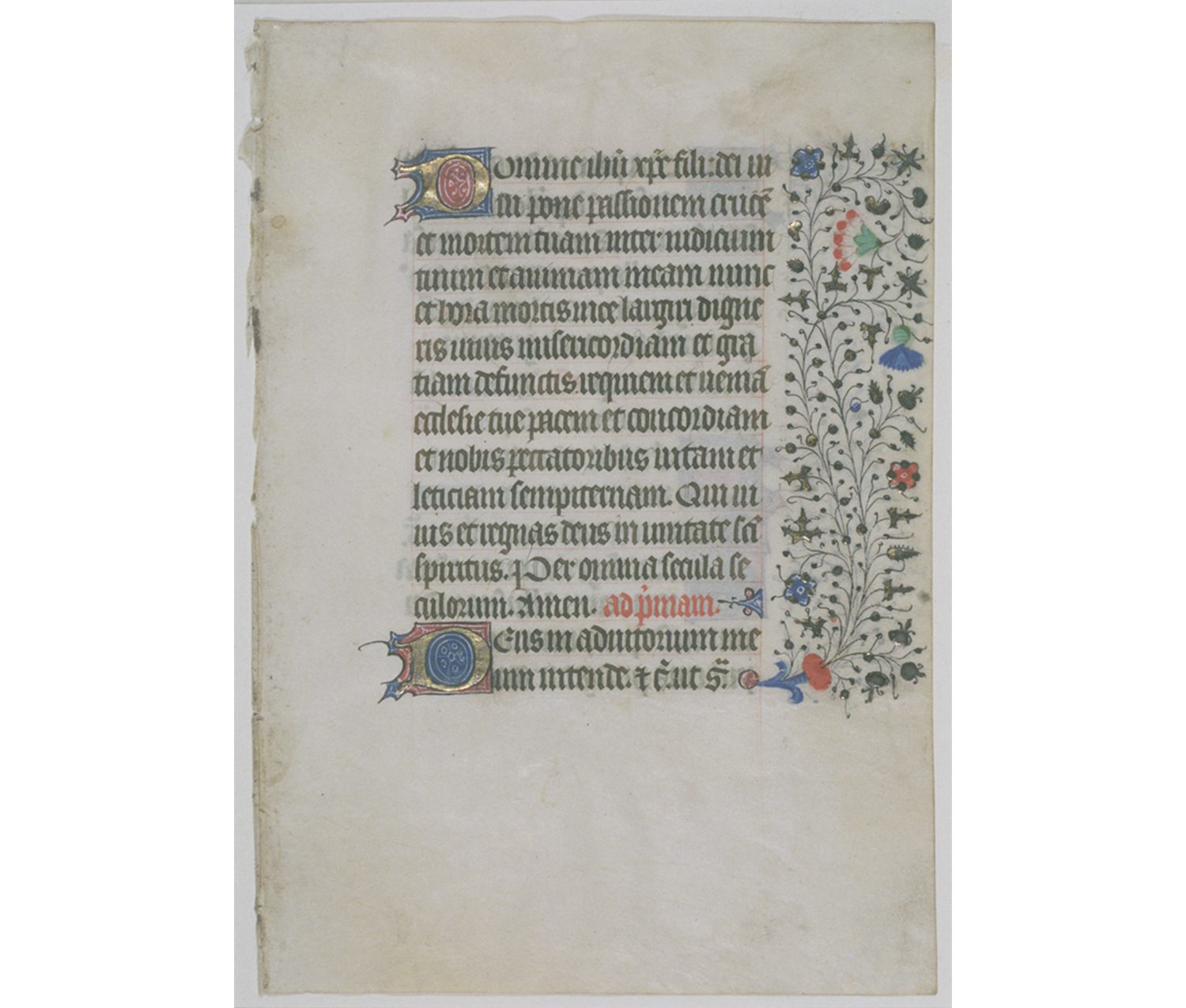

Unknown. French. Manuscript Leaf, from a Book of Hours, ca. 1480. Tempera, ink, and gold on vellum. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1950.144.

One can also see the faint margin lines on the outer edges of this page, providing the scribe and artist (these were usually separate roles) a layout to work within. The words in red ink would have actually been done by a third person, generally known as the rubricator. Rubrics were used to indicate titles, headings, or other important words in the text.

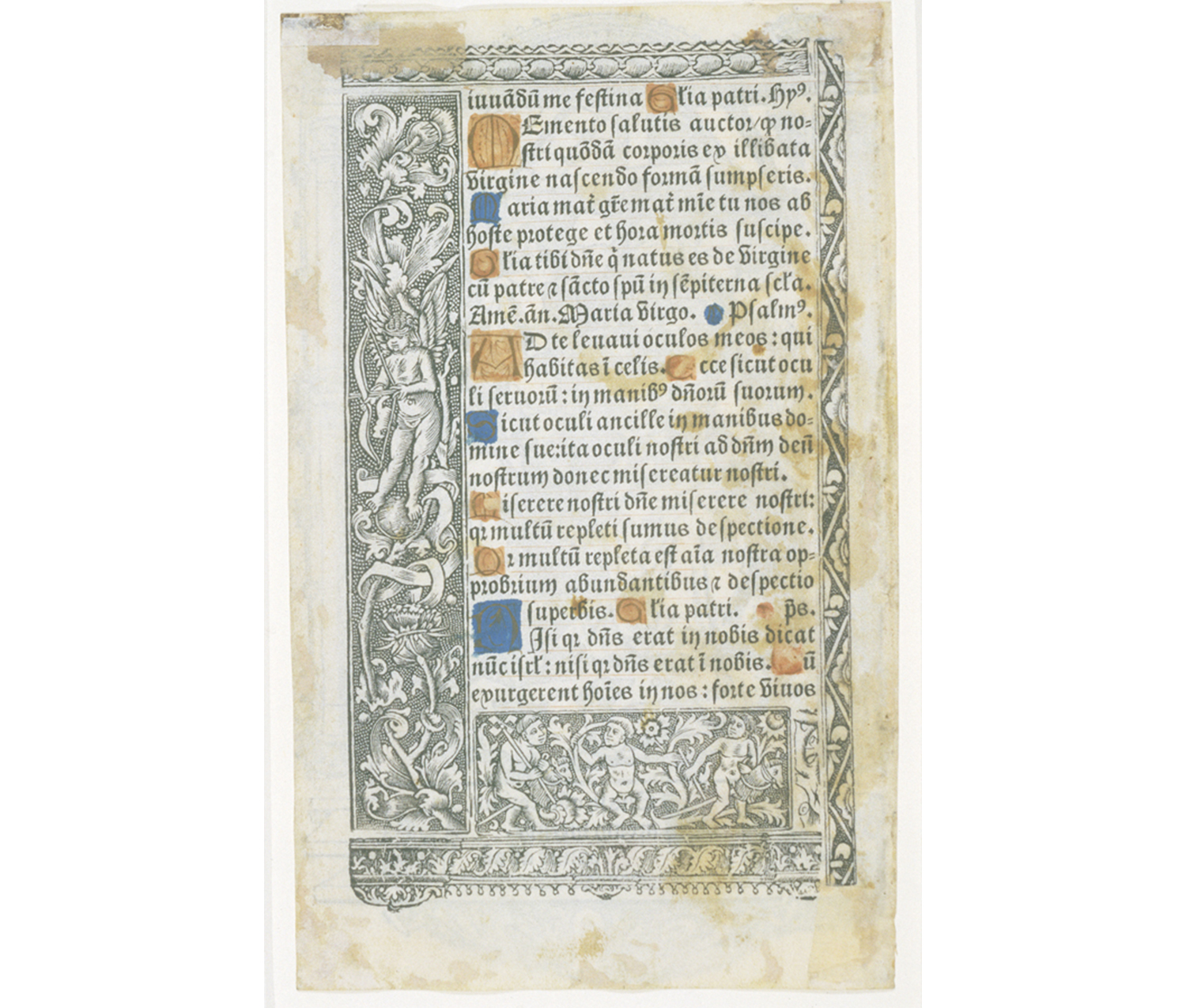

Gillet Hardouin (published by). French. active 1491–1521. Adoration of the Magi (recto); Text with Border (verso), from Livre d'Heures, n.d. Metal cut text with hand illuminated letters in red, blue and gold on parchment. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1950.32.

This page from a later book of hours was not hand-lettered, but made using metalcut prints. Still, it uses many of the stylistic conventions found in earlier manuscripts—the elaborate illustrated borders and the hand-painted red and blue initials, for example. By the early 16th century, printed books could be produced faster, in greater numbers, and at a lower cost than their handwritten counterparts, meaning that elaborately illustrated books were no longer limited to the very wealthy.

Adoration of the Magi (recto)

The opposite side of the page also depicts an Adoration of the Magi scene; again, even though the page was made in a completely different way, there are striking similarities between it and the previous image. However, both the architectural border that “frames” the scene and the image itself are much more detailed, even crowded.

What is fascinating about Books of Hours is that they were so incredibly adaptable to their audience. Christian worship in the medieval era was institutional, dominated by the clergy and monasteries. The Bible itself was written and spoken only in Latin, rendering it inaccessible to ordinary people without the mediation of a priest. Since religious worship was so important to people of every class, the books reveal as much about their owners as they do their contents.