BOW DOWN

Maggie Kurkoski is a member of the Smith College class of 2012 and the Brown Post-Baccalaureate Curatorial Fellow in the Cunningham Center.

For the past few months I have been working on my corridor show, BOW DOWN: Queens in Art, now on view in the second floor of the Museum. Curating this exhibition was a completely new experience for me. I’ve never worked on a show of prints, drawings and photographs before, nor have I drawn from such a large collection of works. The Cunningham Center has over 18,000 pieces of art, and at first it was overwhelming: how could I possibly know where to start?

Salvador Dali. Spanish, 1904–1989. Queen of Spades, Part of Playing Card Suite, 1970. Lithograph printed in color on paper. Gift of Reese Palley and Marilyn Arnold Palley. SC 1991.49.2c.

Inspiration came in the form of a donation from the Andy Warhol Foundation, two prints from the artist’s Reigning Queens series. Entranced by the image of Queen Elizabeth II, reproduced and manipulated by Warhol, I began to think about the issue of representation: who controls the visual legacy of a royal woman? The seed of the exhibition had been planted.

With the help of my colleagues, I sought out other queens in our collection, and compiled a selection of art that spanned centuries of Western monarchies.

Queen Victoria - Her Latest Portrait, 1900. Purchased with Hillyer-Tryon-Mather Fund, with funds given in memory of Nancy Newhall (Nancy Parker, class of 1930) and in honor of Beaumont Newhall, and with funds given in honor of Ruth Wedgwood Kennedy. Half tone on paper mounted on paperboard. SC 4643.566.

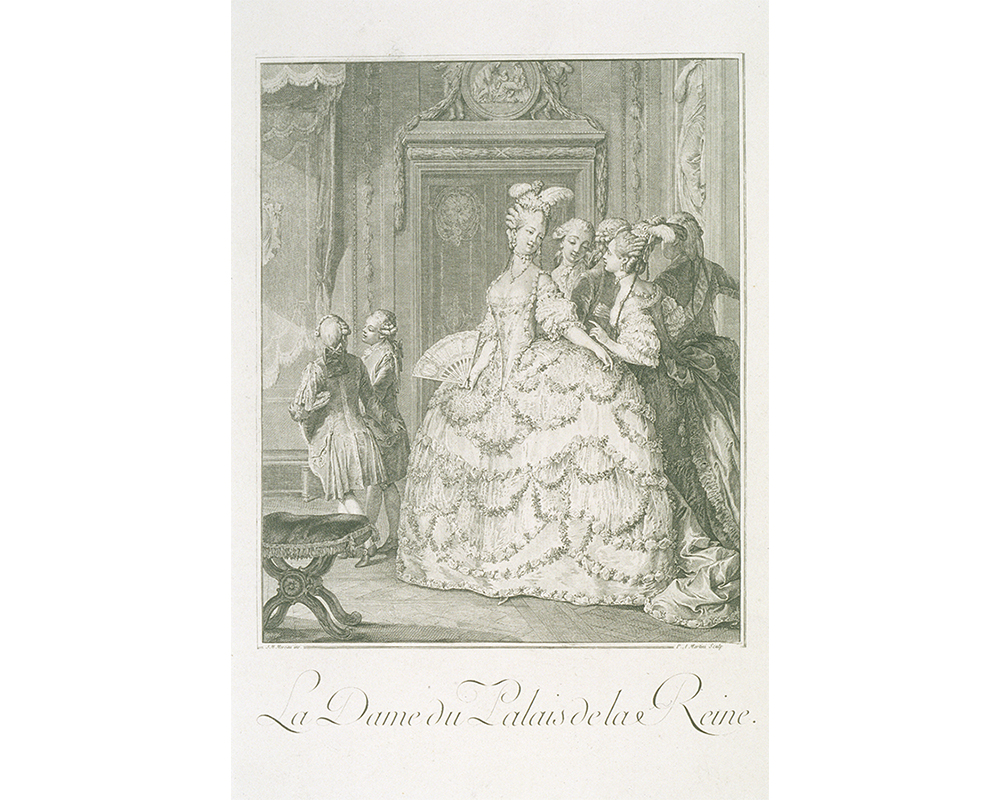

There are fewer queens in the world than a century ago, but our fascination with royal women has continued. Teenagers still swoon over the fashions of Queen Marie Antoinette of France, while paparazzi take endless shots of Kate Middleton, Duchess of Cambridge, never quite satiating our desire to see the newest pictures of this fashionable member of the British royal family.

Although queens have been prominent figures in Western monarchies for the past five hundred years, their authority was often limited. Kings ruled as heads of state, while queens were responsible for continuing the royal family line. When women such as the long-reigning British Queen Victoria and Queen Marie de Medici of France did gain power, they were careful to represent themselves as both royal and maternal, in keeping with the gender norms of their time. Likewise, the ideal queen was beautiful. Artists emphasized the attractiveness of Her Majesty, often improving on her actual appearance.

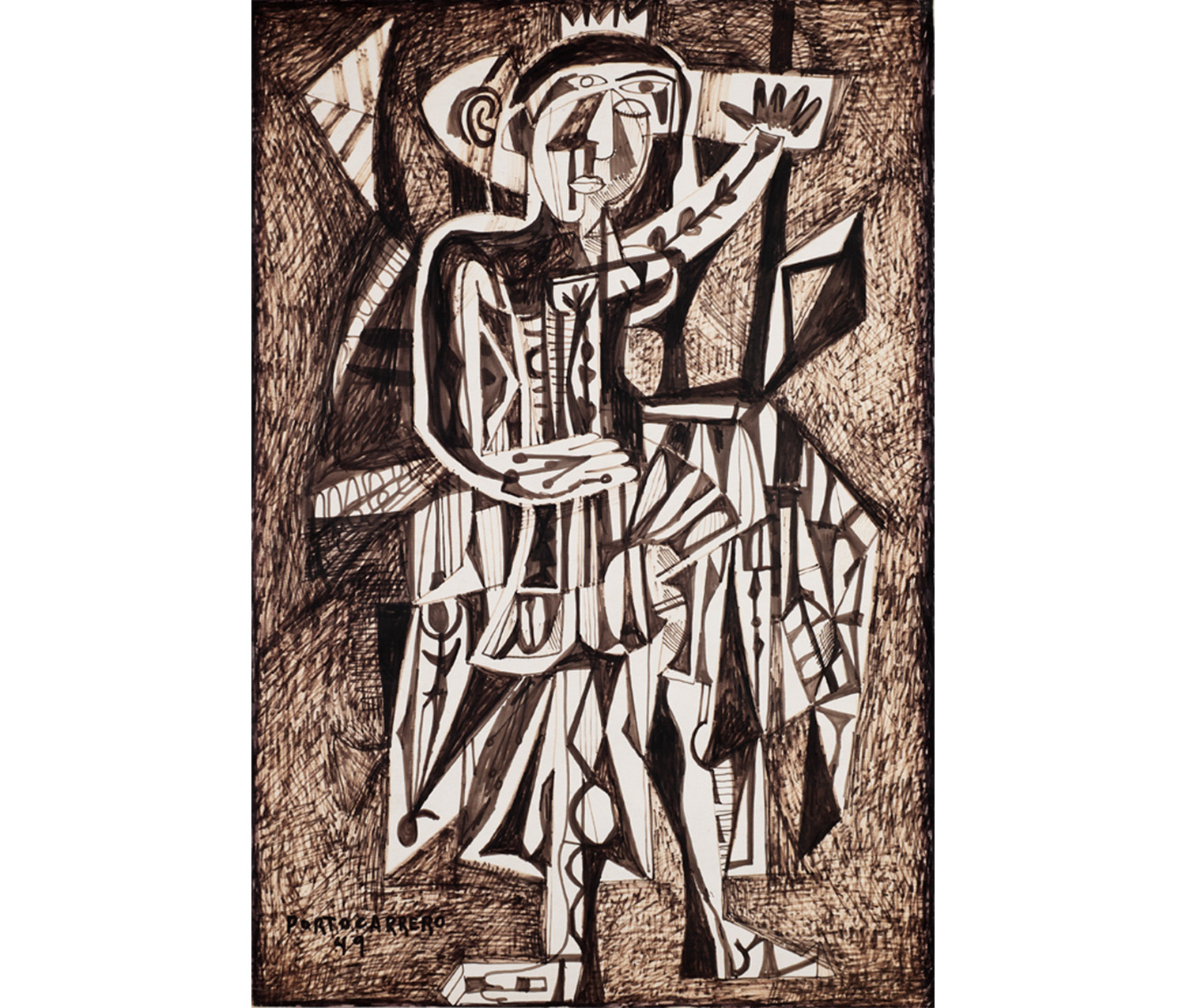

Rene Portocarrero. Cuban, 1912–1985. Queen #2, 1949. Crayon and ink on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph Cantor. SC 1955.57.

For some queens, control of their image was the greatest influence they had on their courts and their kingdoms. No portrait was just a likeness, but a record of court culture and a piece of propaganda that still reveals the mindset of artist and patron alike.

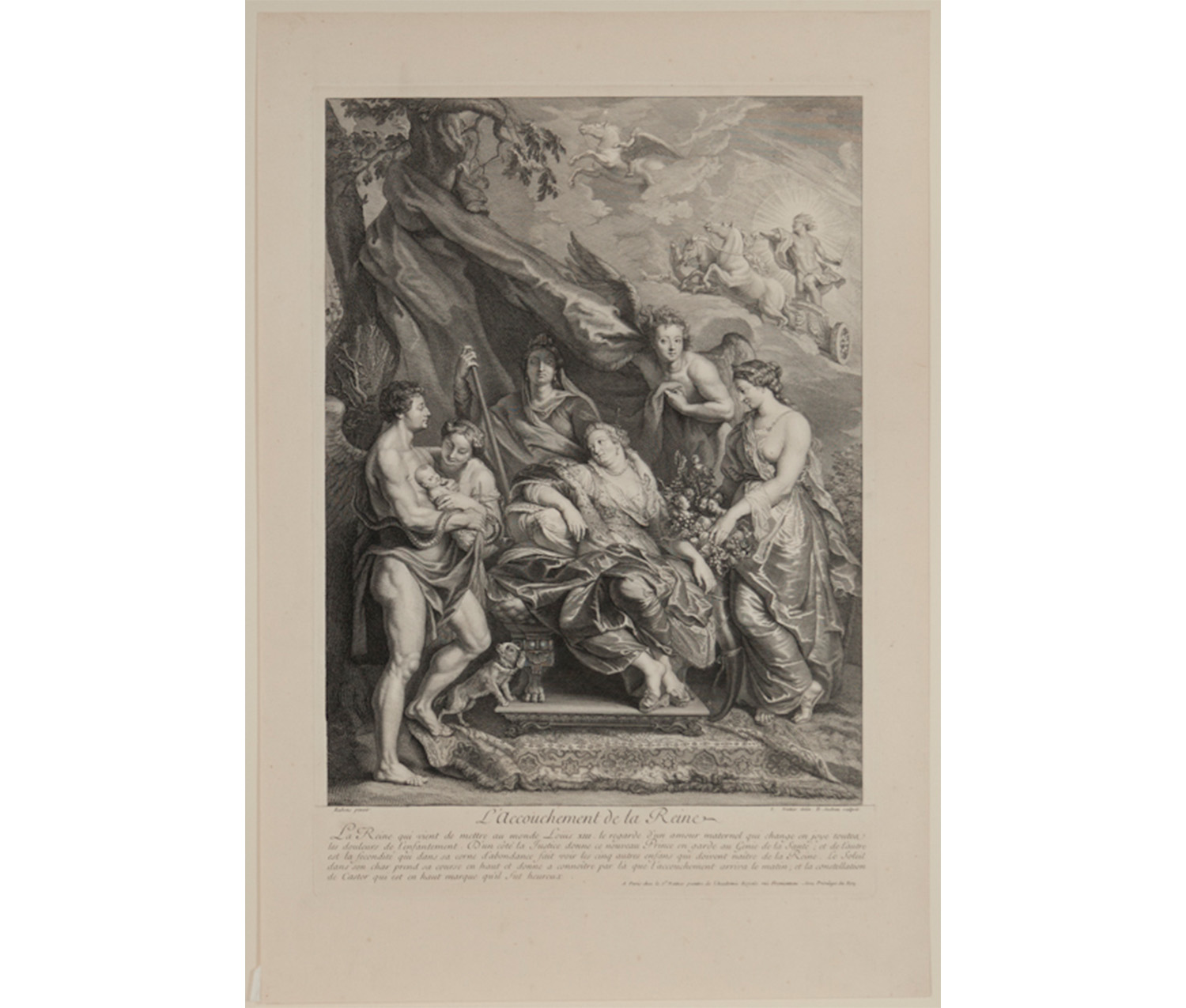

Before the age of photography, prints spread these visual messages about the appearance and life of royals. Often, a painted portrait of a royal was only visible to the court and visiting dignitaries. By translating the painting into a print, artists made these visions of sovereignty available to a wider audience. Many of the works in this show are prints made after large paintings, such as L'Accouchement de la Reine, an engraving on loan from the Mead Museum, Amherst College (shown below).

Jean-Marc Nattier. French, 1685–1766. Printed by Benoît Audran. French, 1661–1721. After Peter Paul Rubens. Flemish, 1577–1640. L’Accouchement de la Reine, c. 1707–1710. Engraving. Mead Art Museum, Amherst College. Gift of the Wise Arts Council. AC 1976.90.11.

The painting on which this print was based was part of a group of works commissioned from Peter Paul Rubens by Marie de Medici, queen of France, in 1621. It was later reproduced by Jean-Marc Nattier; This cycle highlights the major events and accomplishments of Marie’s life through a mythological lens. This engraving celebrates the birth of her son, the future Louis XIII.

Detail of L'Accouchement de la Reine

Marie de Medici, lounging on her throne, is flanked by gods and goddesses from Roman mythology. Her new role as mother to the heir is clear as she looks at her infant. Next to her, a goddess offers her a cornucopia bursting with flowers and baby heads, a gift of future fecundity. The queen has crafted an image of herself as devoted mother and powerful regent.

L'Accouchement de la Reine and the other works in this exhibition reveal the power of art to define our perceptions of public figures. I hope you have the chance to see them yourself!

BOW DOWN is open from September 12 through January 4.