Collecting the Past: Kenojuak Ashevak

Guest blogger Jiete (Jady) Li is a Smith College student, class of 2015. The original version of this work was written for Collecting the Past: Art and Artifacts of the Ancient Americas. This course was offered Spring 2015 by Dana Leibsohn, Priscilla Paine Van der Poel Professor of Art.

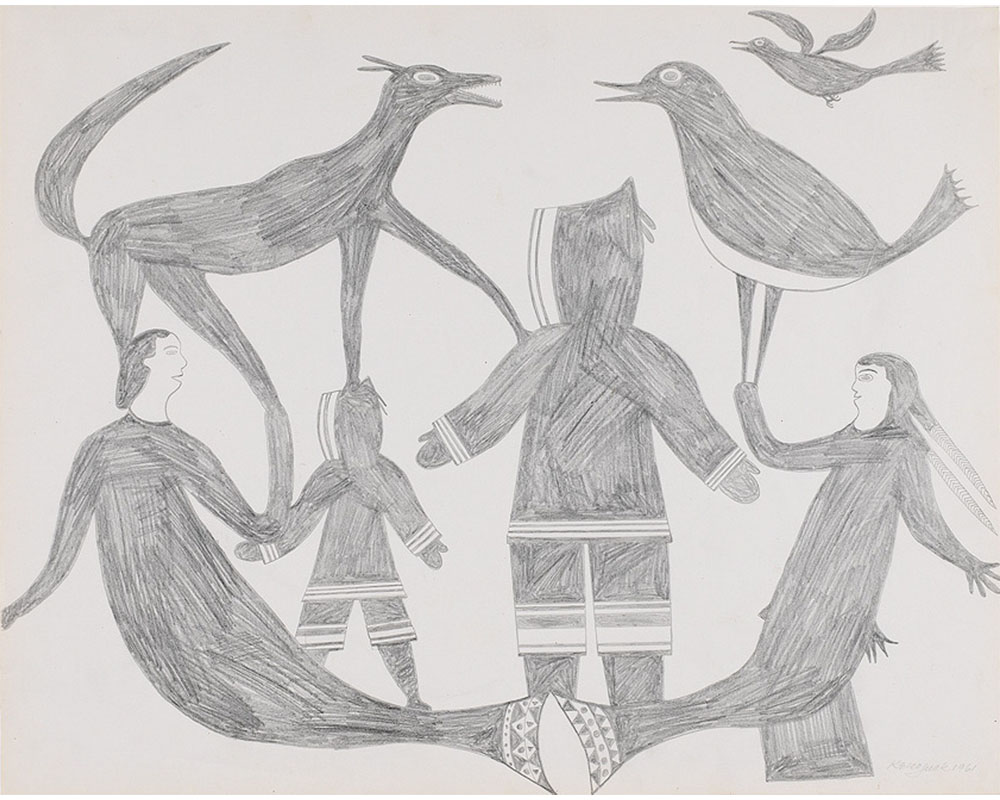

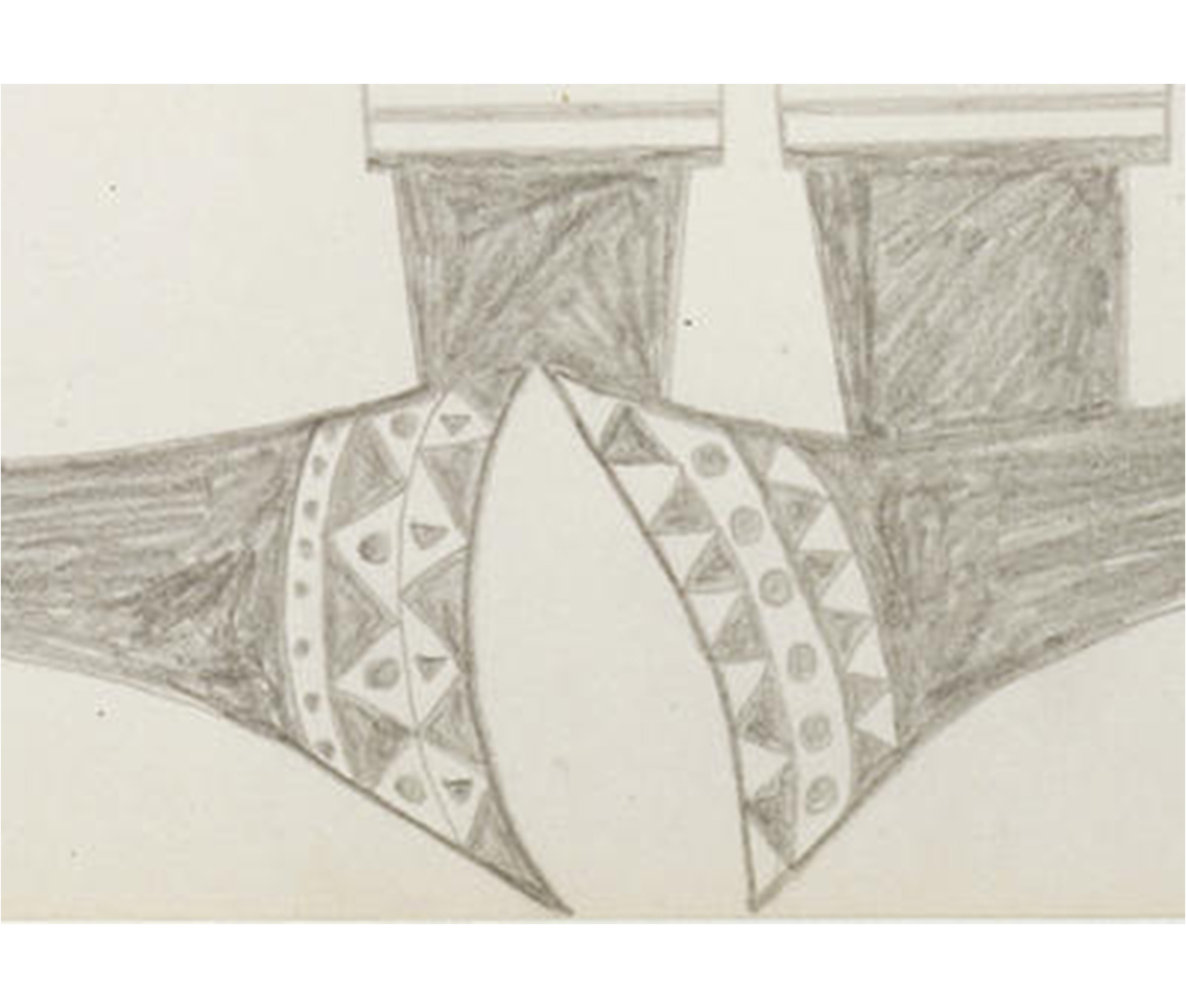

This pencil drawing on wove paper by Kenojuak Ashevak, one of the most well-known modern Inuit artists, represents two human figures encircled by animals and sea deities against a blank background. The absence of a setting seems to indicate an indefinable space, creating an otherworldly and fantastic atmosphere. The two central figures, probably a parent and a child, wear the traditional Inuit parkas. They stand with their backs to the viewer on the decorated tails of two sea deities.

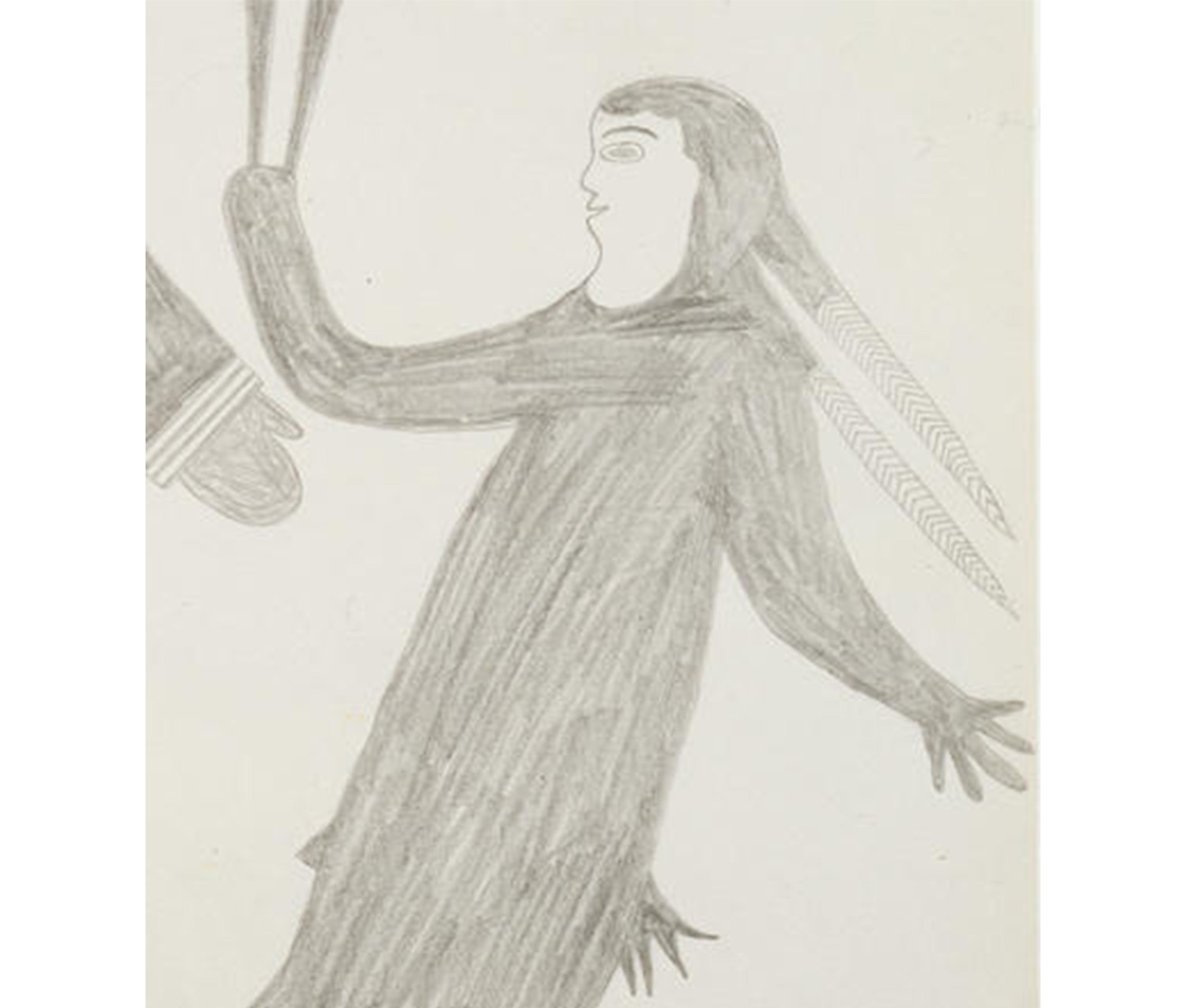

Detail of drawing

Different from the mermaid-like creature on the left, the one on the right with two more long plumes, a squarish fin, and a five-fingered hand may represent the Inuit sea goddess Sedna (detail above) whose fingers have been cut by her father. The hand of Sedna supports a bird facing a wolf (or a sled dog or a fox) whose four legs step on the human figures and the other sea deity. The swirling tail of the wolf echoes with a small bird flying above the big one on the left. The overall composition forms a circle encompassing the central parent and child. The drawing is probably about Sedna’s transformation into the sea goddess or about Kenojuak’s imaginative perception of the world around her.

Detail of drawing

The Cape Dorset printmaking project was developed in the 1950s under Western colonialism: Western ideologies, aesthetics, and interests shaped Inuit people’s identity and arts; simultaneously the aboriginal people learned to see themselves in the ways which mattered to the outsiders. At first, this project was considered a symbiotic “win-win game” for both the Western and native participants, as all stakeholders contributed to the formation of a primitive and exotic representation of Inuit culture to the outside world. The Canadian government sponsored such a program in order to claim sovereignty in the Arctic and find a historical origin of the national identity, while the northern native artists were driven by the economic benefits, catering to the southern patrons.

Detail of drawing

The Cape Dorset project tried to save the “pure” and “authentic” Inuit culture in the rapidly changing modern world under the tight Western control and intervention. The natives consequently faced a struggle between modernization—participation in a market-driven capitalist economy, and primitivization—creation of historical imageries unrelated to their contemporary life. Perhaps because of a lack of autonomy in the production and dissemination of Inuit cultural knowledge in the 20th century, the natives had internalized the romanticized Inuit image created by the Westerners: they saw themselves as how the outsiders saw them.

For instance, the locals believed that Inuit arts produced in workshops supervised by Westerners preserved the pristine and pre-Western contact aboriginal culture and were thus used for educating their children. Passing down knowledge filtered through a Western lens to future generations has further intensified the primitivization of Inuit culture within the local community.

Detail of drawing

Due to the post-colonial repositioning of archaeology and ethnography as well as the political sovereignty of Nunavut, the ethical imbalance and cultural racism between the Western authorities (such as Western founders, managers, and scholars of the project) and native art makers in Cape Dorset were recently acknowledged and challenged. In the last two decades, the Inuit people have become more self-critical, reflective, and empowered to define their identity by themselves, which can be demonstrated in the exhibition An Inuit Perspective: Baker Lake Sculpture. More and more contemporary Inuit artists have started to portray their present everyday life, including modern transportation, costumes, and technologies.

This infusion of Western culture into the Inuit way of life does not make the aboriginal people “inauthentic” or “impure,” but suggests that the Inuit community is a fluid and changing entity participating in the global world rather than a static and culturally determined product. Though outsiders can learn and interpret other cultures, the natives should have the autonomy and freedom to produce, display, define, and disseminate their own culture.