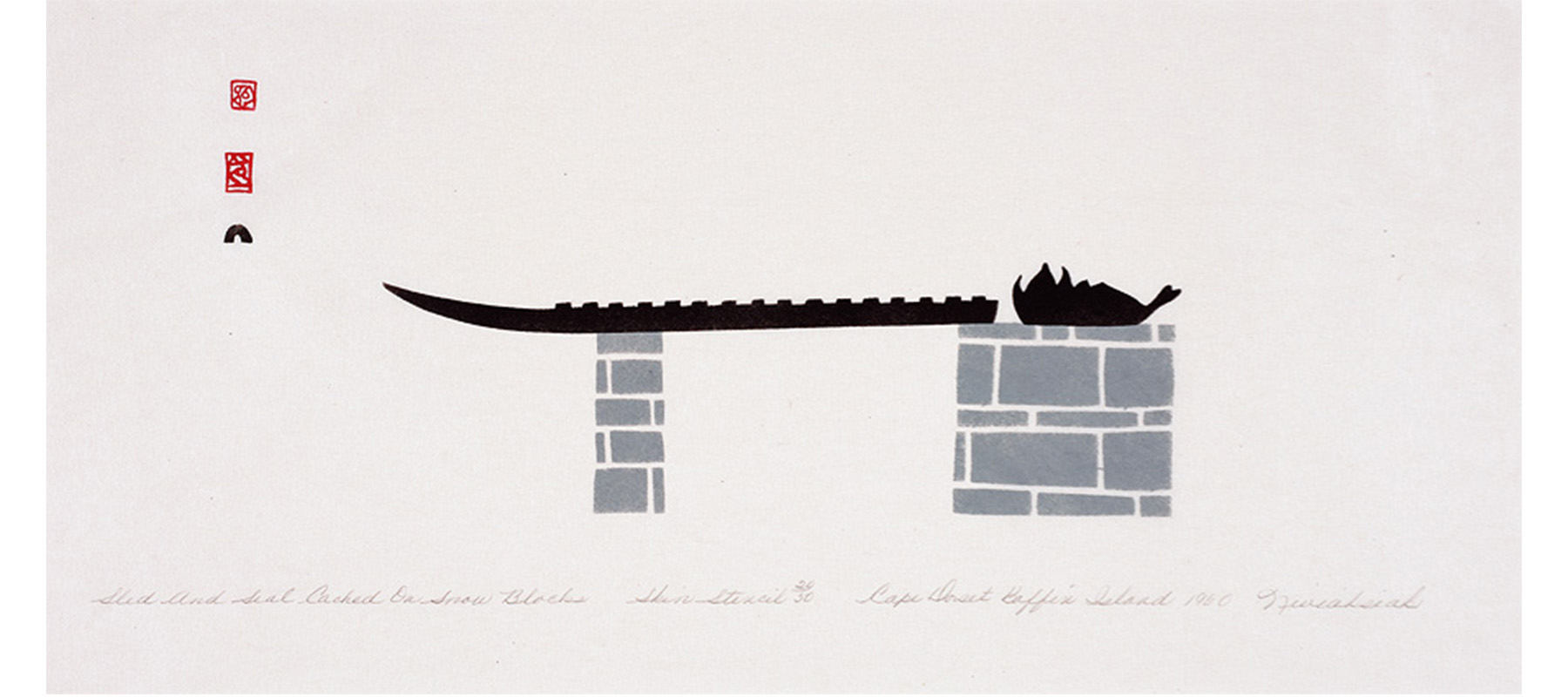

Collecting the Past: Sled and Seal

Guest blogger Emma Casey was a Smith College student, class of 2015 who majored in Spanish. She was also the 2011-2013 STRIDE Scholar in the Cunningham Center for Prints, Drawings, and Photographs. The original version of this work was written for Collecting the Past: Art and Artifacts of the Ancient Americas. This course was offered Spring 2015 by Dana Leibsohn, Priscilla Paine Van der Poel Professor of Art.

The sheer isolation of the Canadian Arctic allowed native Inuit populations to remain relatively uninfluenced by Anglos until the nineteen fifties, when a flurry of government service ventures pushed northward. The Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources tasked the Northern Service Officers with increasing the self-sufficiency of the Inuit. [2] One Toronto-born officer, James Houston, saw economic potential in the crafts, namely carvings, of the Cape Dorset community on Baffin Island, and introduced to them the Western medium of printmaking. The artists’ interest in printmaking links to the exacting process required of Inuit craft and tool production. The laborious precision of the print is not dissimilar to the making of kayaks, igloos, and sleds, which “involved certain aesthetic decisions. […] Everything had to be as perfect as possible, since mistakes in design could have fatal results in that harsh environment.” [6]

Houston saw his work as philanthropic; helping the Inuit artist enliven “the sparseness of his life” (Houston, Beaver). Though at times his musings exoticize “the wildly free talents and desires of the Eskimos”, it is thanks to Houston’s, arguably colonizing, efforts that the West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative was founded, and the prolific printmaking tradition of the Canadian Arctic took hold. [3]

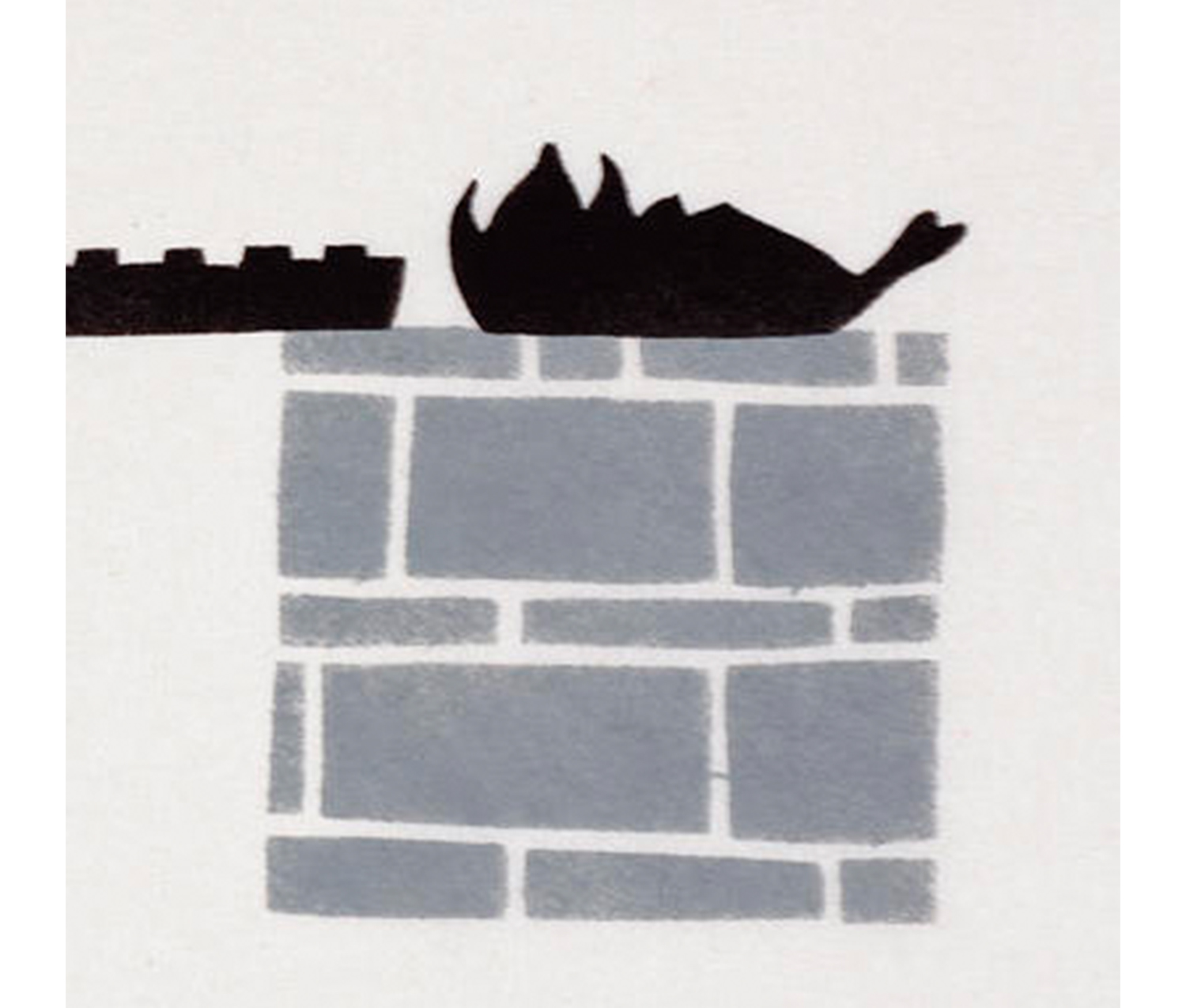

Detail of Sled and Seal Cached on Snow Blocks

In addition to being one of the earliest examples of printmaking in Cape Dorset, Sled and Seal Cached on Snow Blocks forms part of the intriguing experimental technique of sealskin stencil, born of ingenuity and necessity. In the spring of 1958, Houston and his initial recruited artists, namely the celebrated carver Niviaksiak, experimented with the medium – what was to be a short-lived printmaking tradition. [3] The aesthetic of stenciling was already included in the Inuit repertory of decoration. The stencil prints drew from the longstanding art of skin appliqué, a practice of “cutting silhouette forms and designs from animal hides to be sewn onto clothing or other useful objects for decoration.” [3] Houston supervised as patterns were cut into sealskins stretched to a parchment-like stiffness, then, “Using bound brushes of polar bear hair, paint soaked wads covered with caribou skin, and many other successful and unsuccessful devices, the men printed the designs cut by the women.” [3]

Detail of Sled and Seal Cached on Snow Blocks

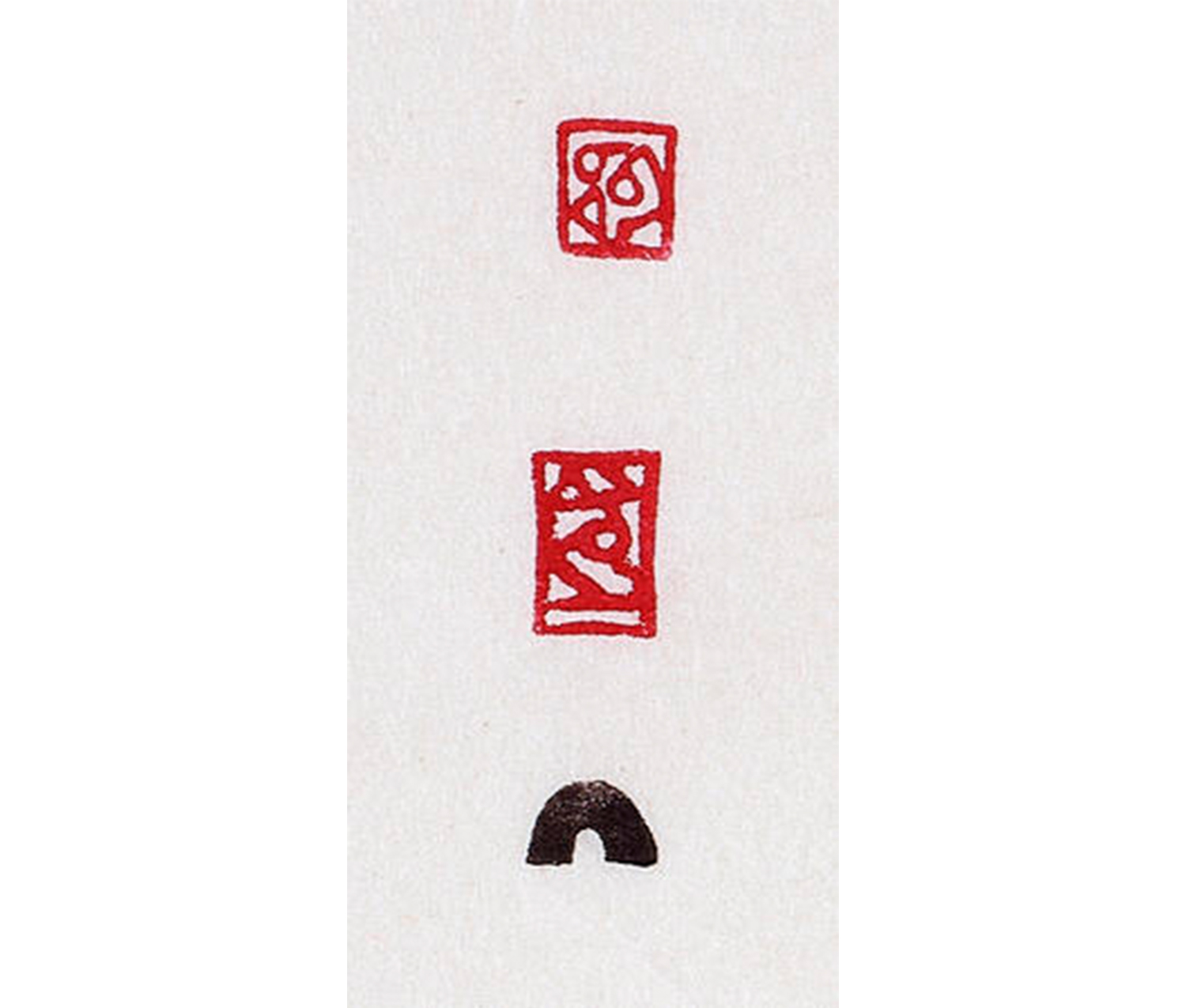

The prints have a unique three-dimensionality in their merging of Anglo medium, Inuit materials, and, most surprisingly, Japanese tradition. In 1958 Houston traveled to Japan for four months to study printmaking under Un’ichi Hiratsuka. The experience resulted in Houston’s contribution of the chop mark to Inuit prints – carved from linoleum fixed to a wooden base and stamped onto the sheet. [6] The chop allows for immediate recognition of the artist, printmaker, and location, in this case Cape Dorset: “a red igloo, although in the early years a black igloo was also used.” [2]

The materials, particular to the ecosystem of the Canadian Arctic, as well as harsh climatic conditions influential in the artistic process, lend Sled and Seal Cached on Snow Blocks distinction. While Houston’s studio project was in its infancy, he was forced to make do with available supplies. Only one shipment of mail reached the island each August, requiring the artists to concoct their own ink from a mixture of seal oil and lamp black, and print on existing stock of onion skin stationery. [3] Applied with brushes of polar bear hair in a stippling technique, the ink, required by the climate to remain liquid in sub-zero temperatures, produced interesting variations of tone. [1] When each print series was completed, the stone block or skin stencil was destroyed, limiting the edition size to preserve uniqueness. [3]

The West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative soon underwent intentional and unexpected changes. The sealskin stencil was abandoned for a much cheaper wax-impregnated cardboard [2], and Niviaksiak passed during a polar bear hunt, before many of the prints were published and Houston’s Co-op gained recognition. [5]

[1] “1972: Cape Dorset prints/estampes”. West Baffin Eskimo Co-operative, Cape Dorset, Northwest Territories. Printed in Canada, 1972.

[2] Crandall, Richard C. “Expanding the Base: 1957-1961.” Inuit Art: A History. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers, 2000. Print.

[3] Houston, James. Eskimo Prints. Barre: Barre Publishers, 1971. Print.

[4] --- and Bert Beaver. Canadian Eskimo Art. Ottawa, Ont.: Department of Northern Affairs and National Resources, 1954. Print.

[5] Lane, Heather. “An Inuit Master Carver: Niviaksiak (1908-1959).” The Polar Museum News Blog. Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, 11 Aug. 2014. Web. 9 Feb. 2015.

[6] Ryan, Leslie Boyd. Cape Dorset Prints, A Retrospective: Fifty Years of Printmaking at the Kinngait Studios. San Francisco: Pomegranate, 2007. Print.