Color and Heat | Bolívar y Juana Azurduy

Guest blogger Ana Sofia Rosas AC '20 is an Ada Comstock Scholar and Cunningham Center Student Assistant. She wrote this post as part of her research for the exhibition Color and Heat: Pan-American works from the AGPA Collection on view on the Museum’s second floor until March 11, 2018.

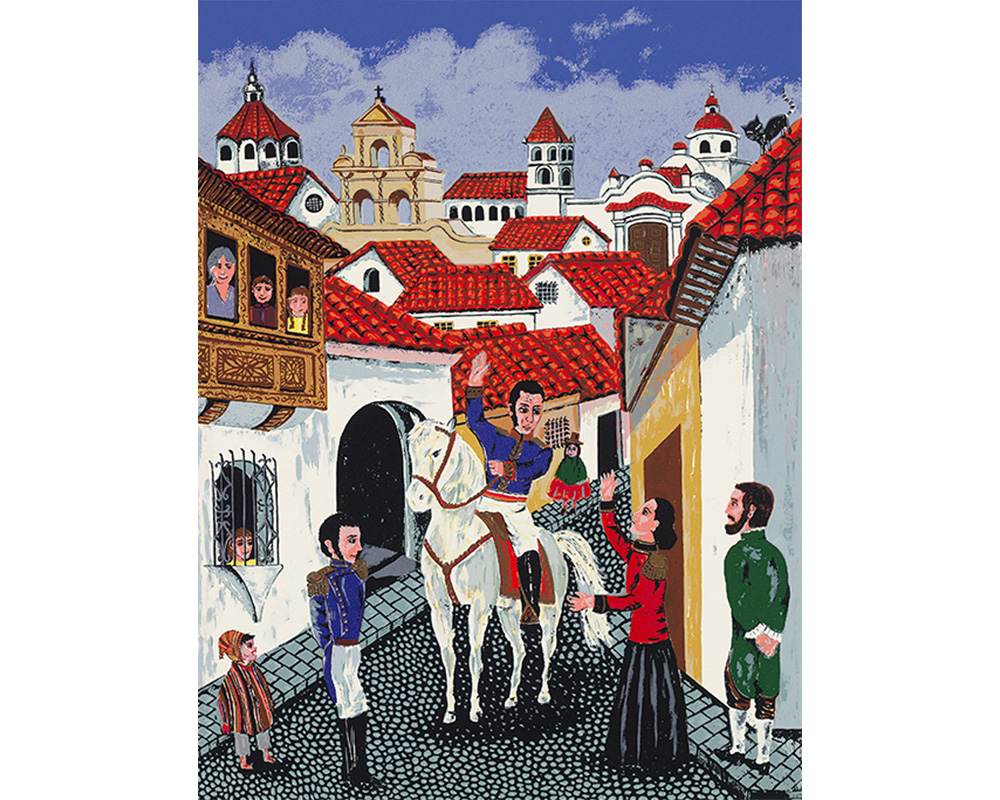

For my first on the job project, I was to learn about Latin American artists whose work would be exhibited in “Color and Heat”, a print show to be displayed in the Cunningham Center corridor. I was asked to write the wall text for several pieces, including the colorful screen-print “Bolívar y Juana Azurduy”. I had done broad research on all the artists in the exhibit, but I chose to write about an artist for whom I found very little information. But her work grabbed my attention with its bright colors and the heroic Simón Bolívar on his white horse. A uniformity in the smiles of every figure illustrated made me wonder if there was another story behind those fixed expressions. I suspected “Bolívar y Juana Azurduy” was not as straightforward as it seemed.

The artist Carmen Baptista was completely unknown to me, and there was little information available on her life and work. We obtained a two-page article directly from an archive in Switzerland, and a leaflet from one of her exhibitions in Bolivia that was given by the donor. So I began to focus solely on the print. The heroic rendering of Bolívar–whose name I associate with courage, and liberation since my grade-school days in Mexico– was not the most prominent element of the print. I felt it was the intimate gesture, the greeting between him and Juana Azurduy. I had never heard of Azurduy —so I began my study there. Azurduy was a guerrilla leader in the region soon to be named Bolivia. She fought alongside her husband Padilla who was also a prominent figure in the fight against the Spanish crown. Azurduy led armies of men and women into battle and defeated multiple strong Spanish brigades. In Juana Azurduy’s campaign for independence, she lost her personal wealth, her husband, and all but one of her children.

The Bolivian nation was established in 1925, but Azurduy did not receive a grain of recognition for her leadership or sacrifice. Her status as a pivotal military leader went ignored, and she never returned to her previous status as a well-to-do woman, she was left a poor widow with her only surviving child. Although she attempted several times to receive some sort of compensation for her bravery in the fight for the now independent nation, she was denied remuneration until the Liberator Simón Bolívar intervened on her behalf. When Simón Bolívar by invitation of the Bolivian president visited the picturesque town of Sucre in Chuquisaca, Bolívar insisted on meeting the forgotten hero Juana Azurduy. Historical accounts tell that shortly after his arrival in Bolivia, he was accompanied by a few of his closest soldiers and the Bolivian leader on a visit to the home of Azurduy. Upon their meeting, Bolívar expressed gratitude to Juana Azurduy for her great courage, but he was astonished at the miserable condition in which she was living. He told his men and the Bolivian leader “this country should not be named Bolivia in my honor, but Padilla or Azurduy, because it was them who made it free”. He then insisted she be promoted to Colonel and be granted a small pension for the rest of her life. Juana Azurduy lived a hard life even with the well-deserved pension she finally received later in life. Her historical importance was undermined after the independence because she was a woman, and even to this day, she is relatively unknown outside of Bolivia and its neighboring countries.

Learning about revolutionary leaders of the Americas was an essential part of my school days in Mexico; I was taught to commemorate the heroes that fought or influenced our independence. Although women played fundamental roles in the revolutions throughout Latin America —Bolivia, Perú, Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Panamá, and México, etc— they are seldom mentioned. It is a ‘liberating’ experience to have a story unfold through research, and greater still to feel that the artist herself has revealed something to you through her work. Baptista’s print attempts to right a wrong and honor the woman who led armies and fought for liberation.