Death in Stasis

Guest blogger Nicole Downer is a Smith College student, class of 2014, majoring in American Studies. She curated the show Death in Stasis, featuring post-mortem photography, as the capstone project for her Museums Concentration.

An important note before you begin: The following blog post includes photographs of deceased individuals, including children. Please be aware if you are sensitive to such imagery.

Death was a fact of life during the Victorian era. People coped with loss through the creation of images of the deceased. The tradition of post-mortem portraiture dates back to as early as the end of the Middle Ages. Deathbed or memorial portraits and death masks were the last images produced of loved ones. Through the new technology of photography, Victorians endeavored to create the illusion of life after death. Post-mortem and memorial portraiture was used to mourn the loss of family members as well as revered public figures.

The Victorians had a more intimate relationship with death than we do now. Death was a part of life and people tended to die in homes rather than hospitals. Mourning the dead was a complex and lengthy ordeal. Depending on the relationship to the deceased, one could be in mourning for up to two years.

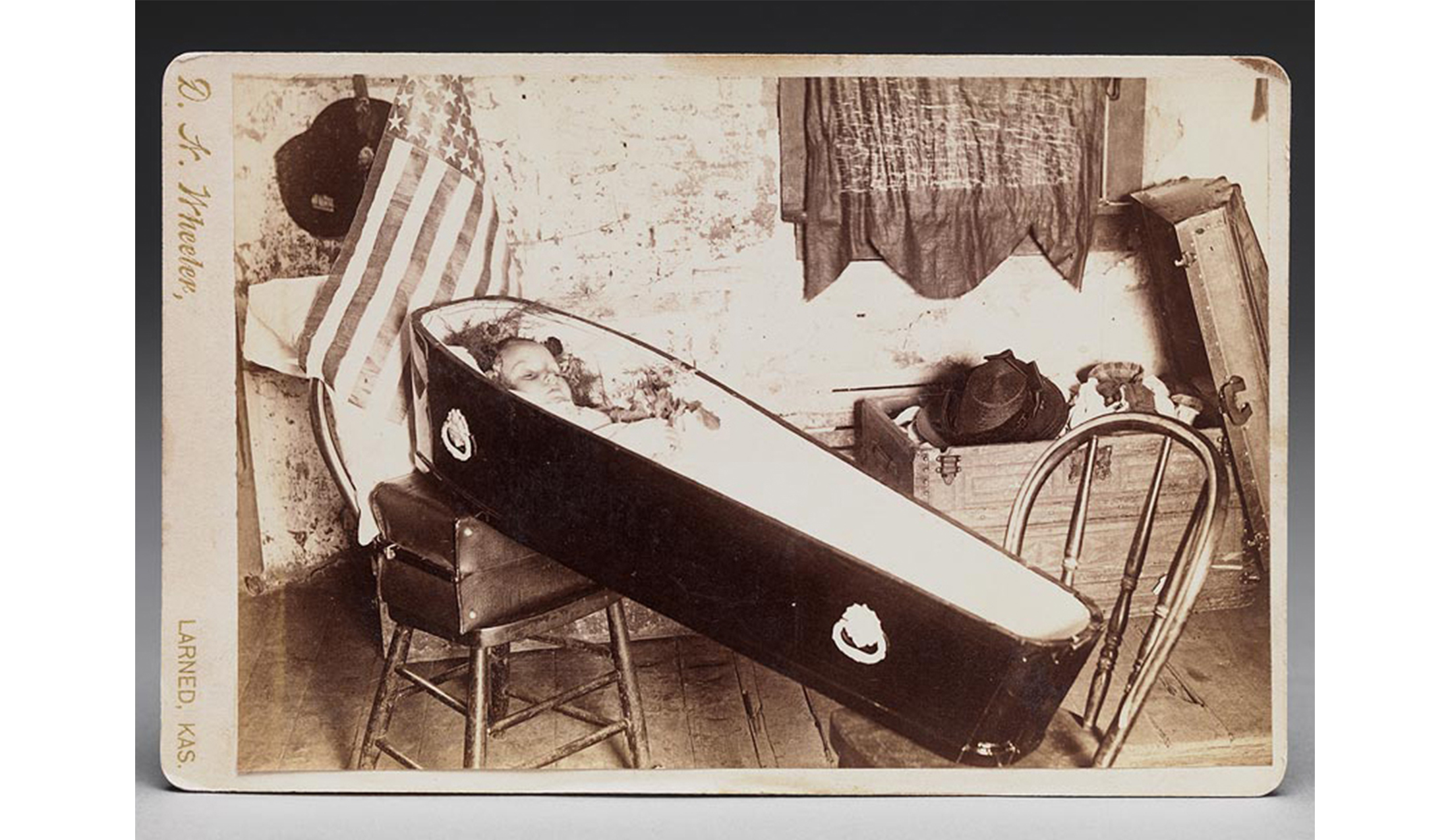

D.N. Wheeler. American. Interior with child in coffin, ca. 1867. Toned gelatin silver print mounted on paperboard as a carte de visite. Purchased with the Rita Rich Fraad, class of 1937, Fund for American Art and the fund in honor of Charles Chetham. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2009.25.1.

For women, mourning involved strict dress codes which limited the colors and materials a woman could wear. Widows could remain in mourning for the rest of their lives as Queen Victoria did after the death of her husband Albert.

Unknown. American. Deceased child with hand painted flowers, ca. 1865. Tintype with hand coloring in 1/2 book-style case. Purchased with the Rita Rich Fraad, class of 1937, Fund for American Art and the fund in honor of Charles Chetham.Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2009.25.2.

Victorians honored the dead through clothing and remembered the dead through objects and art. Death culture influenced all aspects of Victorian life. Clothing, art, photography, and literature of the time period all reflect the closeness people had with death.

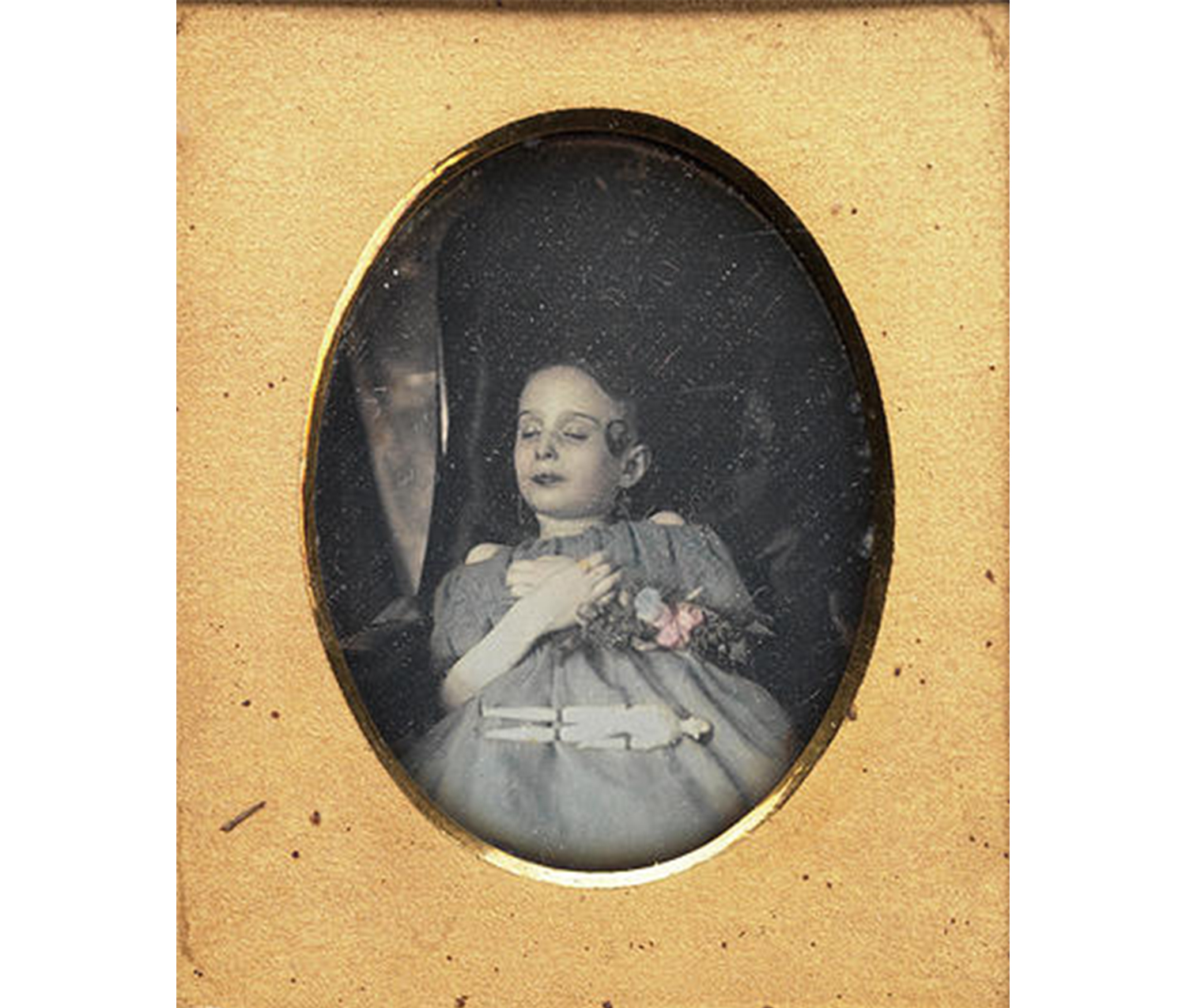

Unknown. American. Deceased child in blue dress with hands crossed over chest, ca. 1850. Hand-colored daguerreotype in book-style case. Purchased with the Rita Rich Fraad, class of 1937, Fund for American Art and the fund in honor of Charles Chetham. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2009.25.3.

Photographing the dead was a common practice in the Victorian era. Journals of photography offered advice to photographers on how to pose bodies and set up lighting. Posing adults for post-mortem photographs often involved propping the body on a stand. It was common to open or paint on eyes to make the body appear alive. Most post-mortem photographs were of children due to high infant mortality rates.

Detail of Deceased child in blue dress with hands crossed over chest, ca. 1850

Post-mortem photography provided families with an image of their lost loved ones who had not been previously photographed. The majority of these photographs were of children and infants. The Victorians had a close relationship with death because of high mortality rates. Death and mourning were a large part of Victorian culture. The works displayed in this exhibition show Victorian mourning through art and photography.

Taking a photograph in the Victorian age was an expensive and time consuming process. Many people, especially children, did not have a photograph taken before they died. Post-mortem photographs gave families an image to remember a lost loved one.

By the twentieth century, advances in photographic technology made post-mortem portraits irrelevant. Photographs became easier and cheaper to take. Most people in the twentieth century had many pictures of their friends and family. We still use photographs to remember our lost loved ones but we no longer have the need for post-mortem portraits.