On Display: Cultural Cannibalism

Guest blogger Alice Matthews is a Smith College student, class of 2018. This post grew out of an assignment for the first-year seminar “On Display: Museums, Collections, and Exhibitions” taught by Professor Barbara Kellum in Fall 2014. As the culminating project of this class, four thought-provoking juxtapositions have been put on view in Museum until February 11, 2015. This juxtaposition can be seen in the ancient art section of the galleries on the second floor.

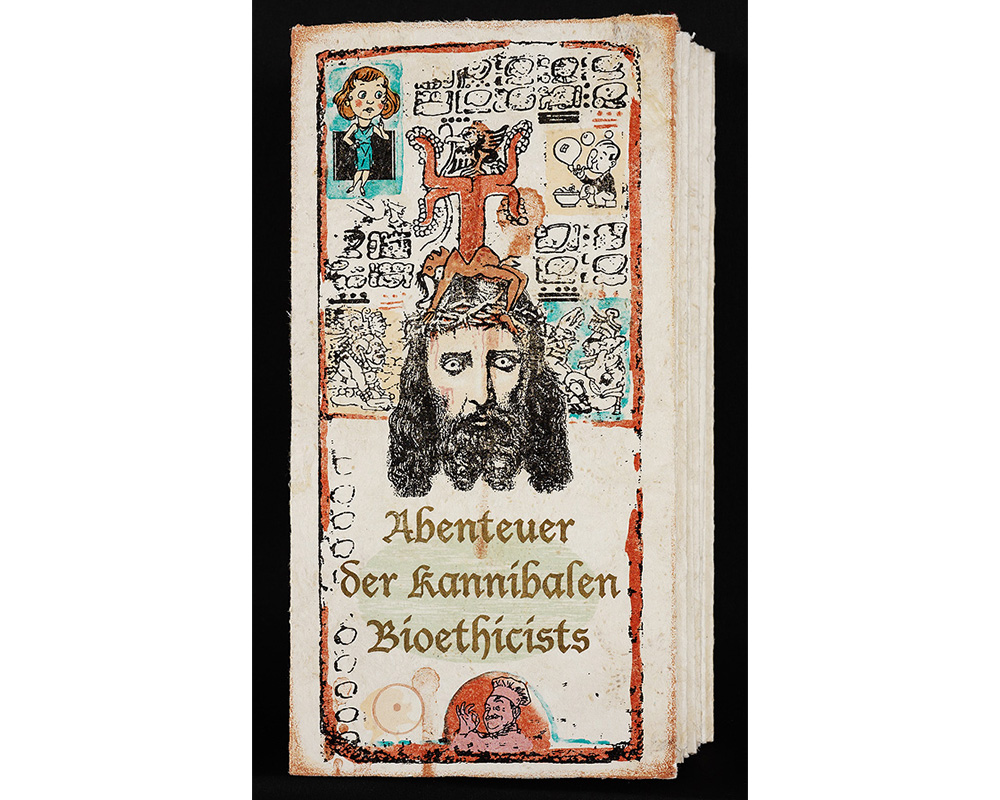

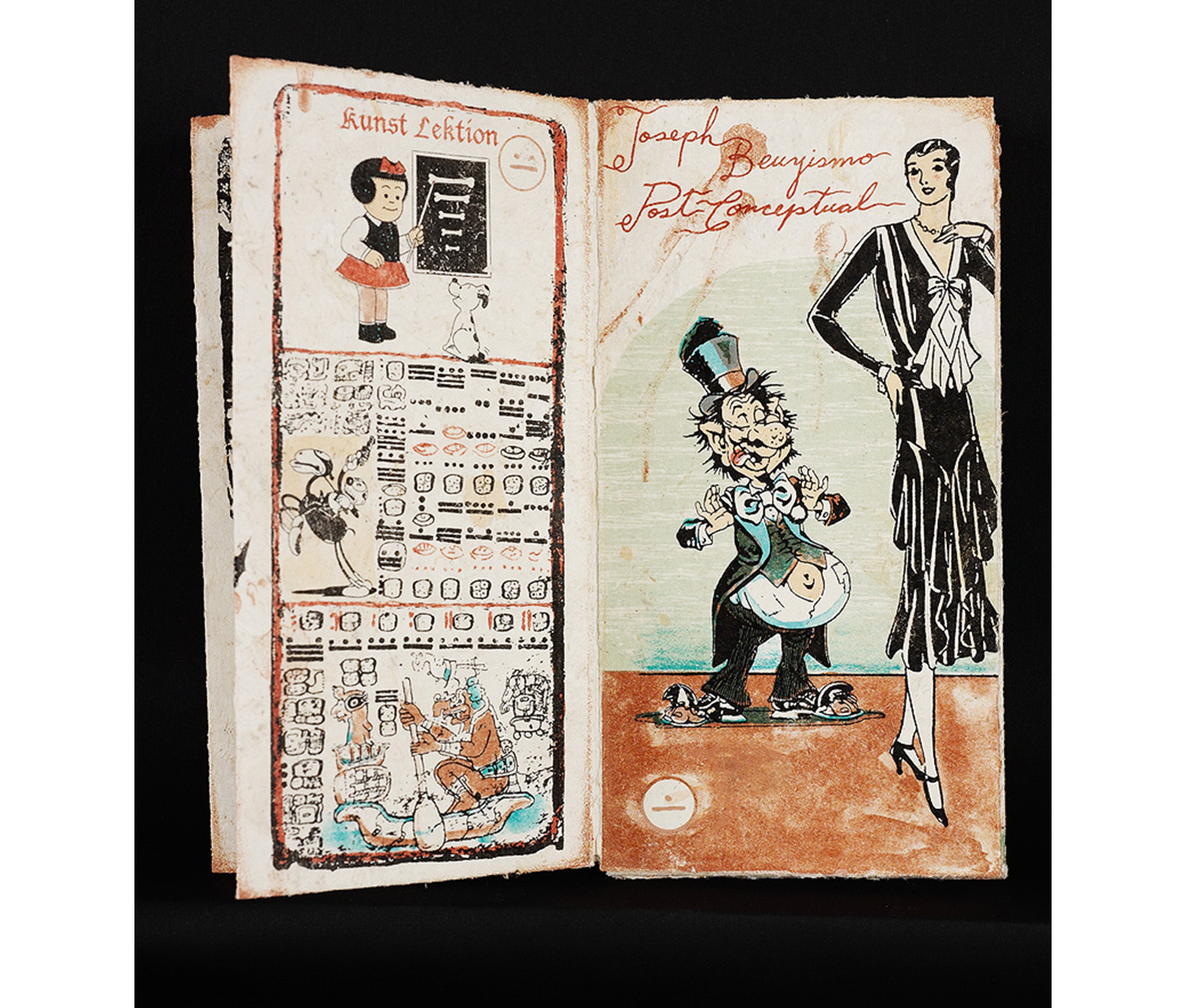

Enrique Chagoa’s Abenteuer de Kannibalen Bioethicists is a 92 inch long accordion-folded artist book that utilizes dynamic graphics to explore the concept of a world in which Pre-Columbian Mesoamericans defeated, conquered, and colonized the Spanish and subsequently the western world. When paired with SCMA’s collection of Mesoamerican art, specifically the Standing Female Figure with Child and Pot, this work brings up questions about the ethical implications of both the physical and psychological appropriation of culture.

Pre-Columbian (Nayarit). Standing Female Figure with Child and Pot, n.d. Clay. Gift of Gail Binney Sterne. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2010.66.9.

Side view of Standing Female Figure with Child and Pot

Historically, the acquisition of ancient art and artifacts has been problematic. Often cultural objects were looted from archeological digs or explorations without consent or consideration of how this theft would affect the indigenous group to which the objects belonged. Currently purchasing ancient art is made much more difficult as a result of international standards set by the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. In 1970 UNESCO made the decision to require museums in the United States to obtain documentation that a purchase or gift was inside its borders before 1970. Standing Female Figure with Child and Pot was donated in 2010 without much documentation. However, after extensive research it was determined that this pre-Columbian art object did in fact meet the required UNESCO criteria. Now that we legally have this object in our possession we are left to question the arbitrary nature of this rule. This cut-off date does not eliminate the possibility of this item being looted as it may have simply been stolen before 1970. How can we justify obtaining an ancient work in 1969 while we ban the collection of these items from 1971? If not 1970, then when? At what point are we willing excuse the literal theft of culture as an unavoidable reality? Chagoya attempts to answer, or at least further explore these questions.

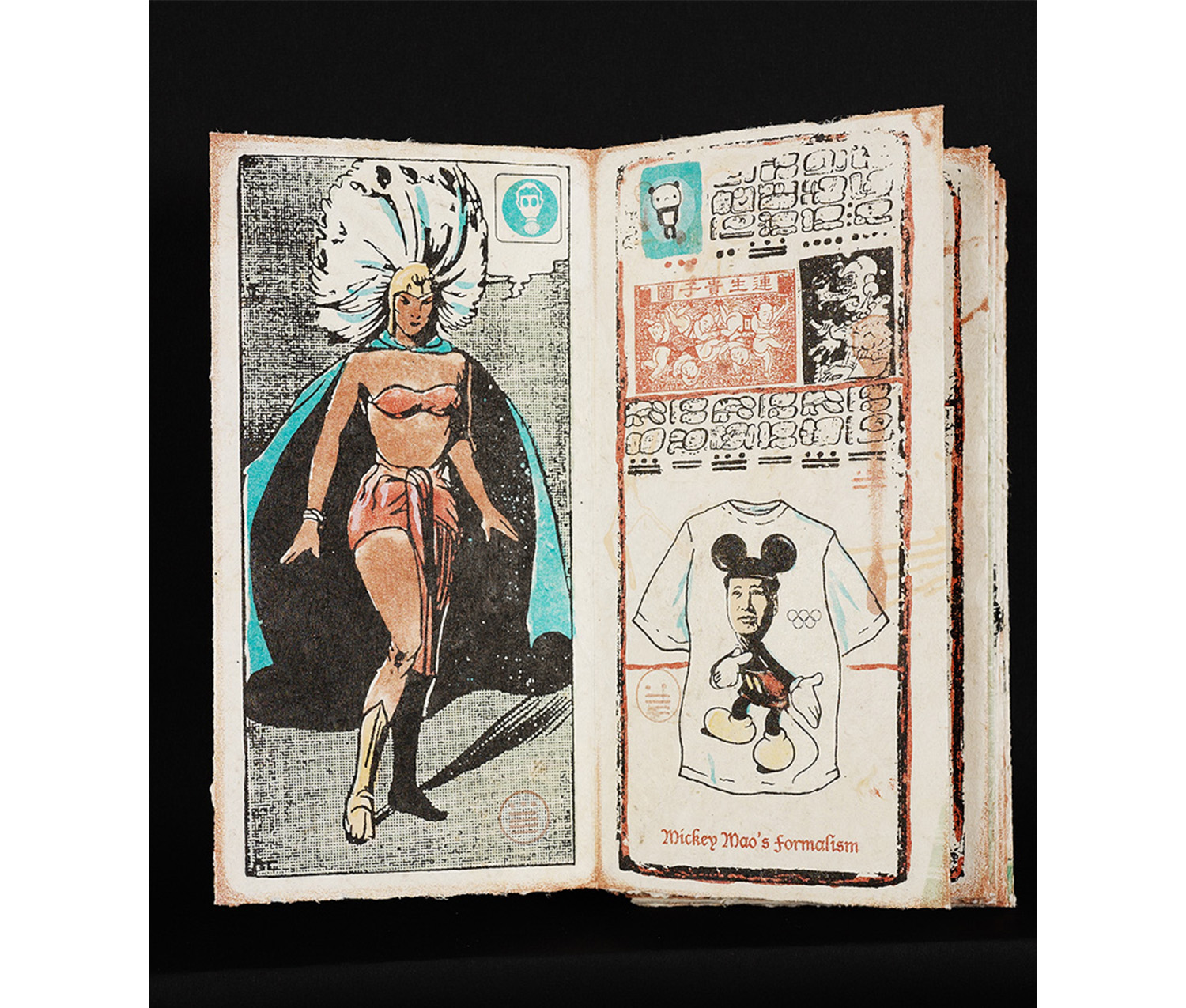

Detail of Abenteuer de Kannibalen Bioethicists

Detail of Abenteuer de Kannibalen Bioethicists

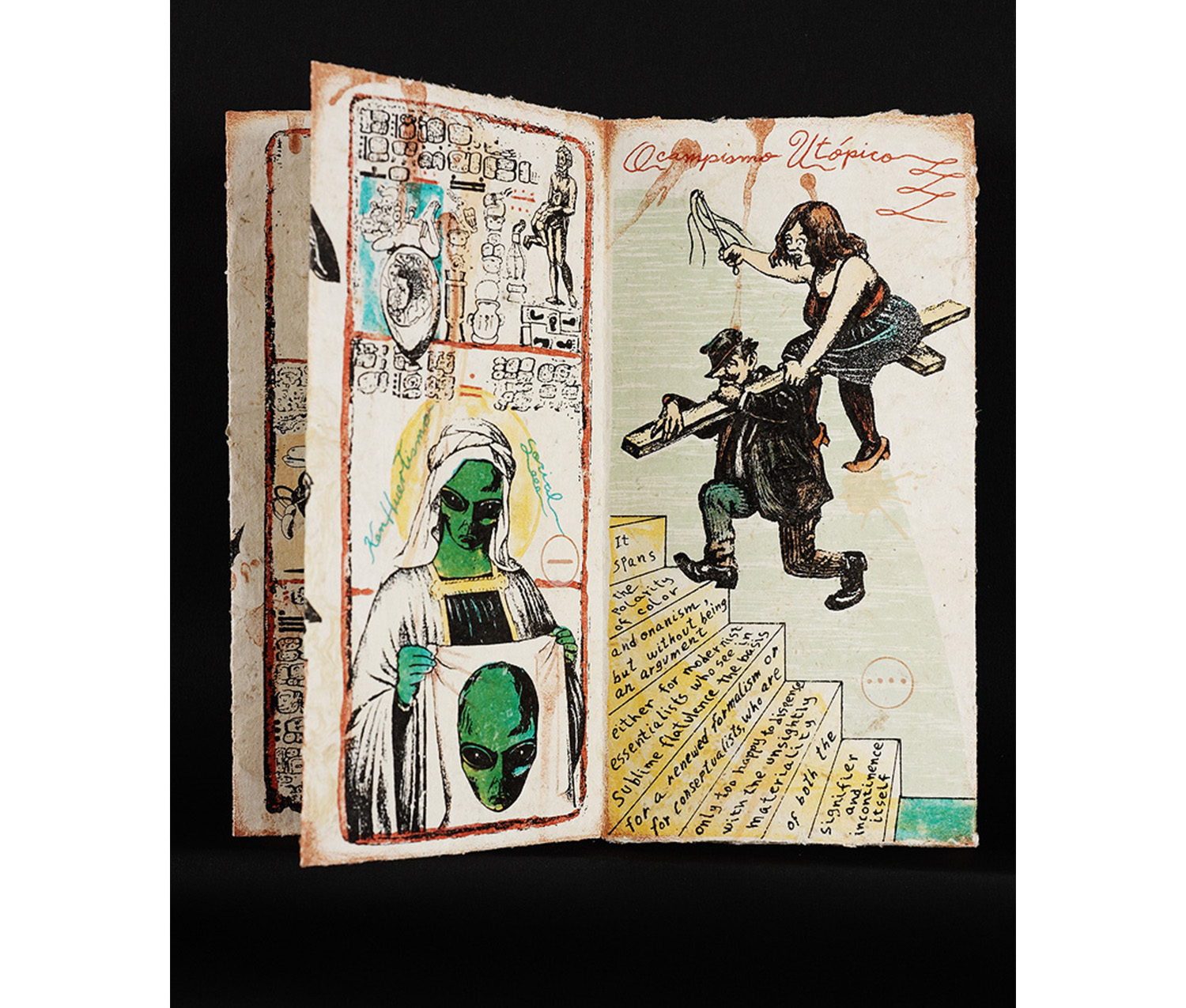

Abenteuer de Kannibalen Bioethicists explores the appropriation of Mesoamerican imagery and culture and how that affects the lens through which we view the history of ourselves and others. The title of this piece is German and can be translated to “The Adventure of the Cannibalistic Bioethicists” which beautifully encapsulates the topics displayed in this work. Cannibalism is used as a metaphor for how dominant western cultures have rewritten history by taking images, traditions, and ideas from other cultures and exploiting their form and aesthetic value while removing much of their function and context. The medium utilized by Chagoya is also significant to his intent. The work utilizes amate paper which was a type of paper produced by pre-Hispanic peoples in massive quantities for both in sacred and secular practices. Their libraries were filled with codices made out of this fig bark fiber but many were destroyed or stolen when the Spanish arrived, leaving very few surviving books. Chagoya is using the medium of a book printed on amate paper in order to recreate what was taken from by taking from others to create his wide array of printed images.

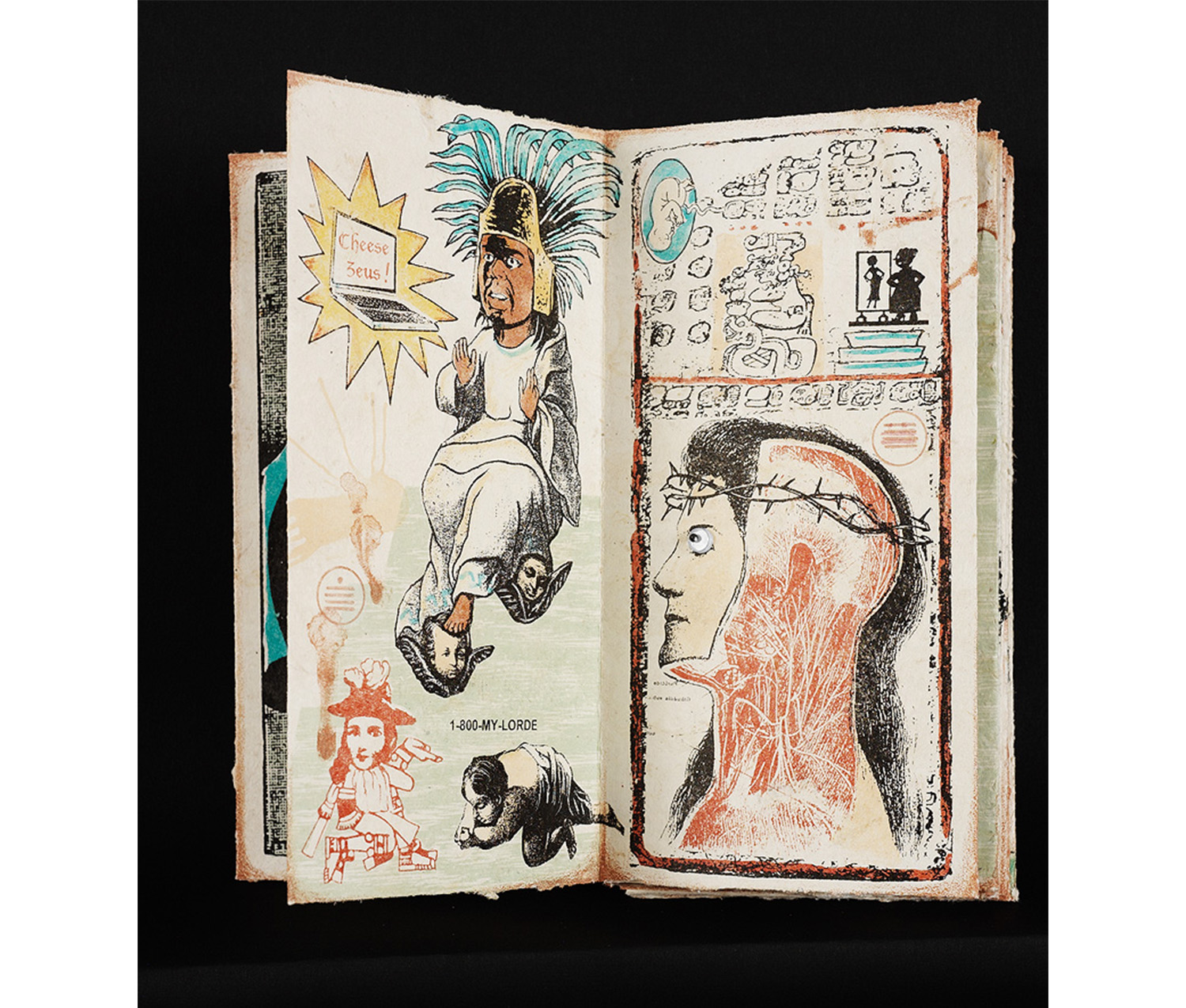

Detail of Abenteuer de Kannibalen Bioethicists

Detail of Abenteuer de Kannibalen Bioethicists

In the same way that Pablo Picasso used the imagery of African masks in his famous painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon purely for their aesthetic value, Chagoya is taking iconic American imagery, like Warhol’s soup cans and Mickey Mouse, and Christian iconography and rendering their context irrelevant. Mickey Mouse now has the face of Mao Zedong on the backdrop of a white t-shirt that also contains the Olympic emblem. Jesus is seen in profile with googly eyes as an anatomical model of the brain and vertebrae. These appropriated items lose their original meanings and the page becomes chaotic and humorously confusing. Many viewers have been perfectly comfortable seeing pre-Columbian figures holding burritos as decor in Chipotle restaurants across the county, and commodifying the image of Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara by purchasing a mass produced cotton T-shirt through the free-market, but when given images that clash because they are aware of their original purpose, viewers are taken aback. Placing Chagoya's cartoon versions of Mesoamerican imagery in relation to a real piece of pre-Columbian art will hopefully spark important discussions of cultural integrity and how to appreciate interesting cultural iconography without white-washing it and claiming it as our own.

Detail of Abenteuer de Kannibalen Bioethicists

Back view of Standing Female Figure with Child and Pot

This ceramic figure has been traced to Nayarit in Western Mexico where humans have lived for as long as 7,000 years. Hernán Cortés became the first European to step foot on the shores of Nayarit and was soon followed by the infamously foul Nuño de Guzmán who subsequently became governor of Mexican provinces that included Nayarit. The Spanish control of this area was always being threatened and disrupted by the indigenous peoples who led many revolts and uprisings. The history of the constant push for independence and reclamation of what belongs to the culture that created Standing Female Figure with Child and Pot makes this juxtaposition all the more meaningful. While it is likely that this heavily adorned woman is only half of a pair of figures used for marriage celebrations and the decorative details indicate the social status of this woman, it is hard not to apply its modern context to her narrative. The ceramic woman is colored in a dark, deep red with dotted lines running down her face mimicking tears as her face expresses her fear and she holds a child behind her as if to shield it from the evil that was going to come to the shores of their homeland. Although this work was created centuries before Europeans came to the Americas, it is interesting to view this sculpture as early foreshadowing the horrors of colonization. This female figure represents what was stolen while Abenteuer de Kannibalen Bioethicists represents the fight to take her back. Now, as a museum, we are faced with the problem of expanding the value of these kinds of Mesoamerican works that are underrepresented in many United States collections, while ensuring that we maintain the integrity of these works and the people they belong to.

Detail of Standing Female Figure with Child and Pot

Standing Female Figure with Child and Pot and Abenteuer de Kannibalen Bioethicists are currently on display in the Ancient Art galleries, second floor, until February 11, 2015