Photo taken by Z Stevens

Do the Clothes Make the Man?

Z Stevens ‘25j is an English Major and Museum Concentrator. They are a Student Museum Educator working with K-12 school groups.

The Falconer, Unknown. Photo taken by Z Stevens. SC 1933.1.1

If a visitor to the museum enters the first floor Brought to Life Exhibition through the front door like they are supposed to, the sculpture of a Medieval man with a bird on his hand will be one of the last things they see. Better known as The Falconer, the statue is just over two feet high, and does not look like any other Falconer a viewer would have seen.

I was first introduced to The Falconer in a 2022 January Term class with Curator Danielle Carrabino, where we focused on the pieces in the Brought to Life show and the history of European painted wood art. Originally, I was not the biggest fan of the piece, but after learning more about its complicated history and lack of origin, I became invested. But, despite my initial interest in him, I never followed up on any research on him beyond the class.

That changed when I took an introductory course on costume design with Professor Kiki Smith, dress historian. Over the semester, the more I began to think back to The Falconer, and the more I began to wonder just where he was supposed to be from? As an undated piece, I decided to start with what I could find out: what era his clothing represented.

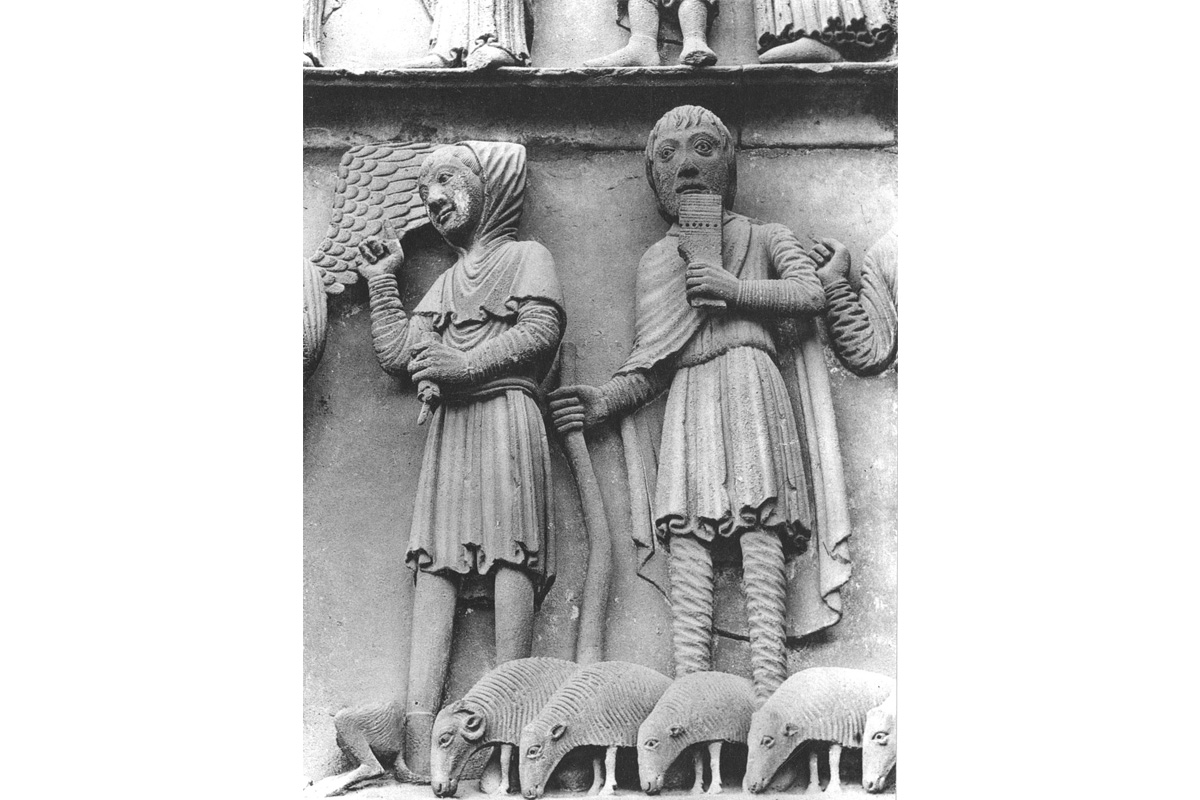

After seeing a photograph of shepherds on the side of the Notre Dame Cathedral during a class discussion of the 12th century and 13th centuries, I decided to use the class text, Lucy Barton’s Historic Costume for the Stage, published in 1935. Exploring the historical sections and using the knowledge that the legs and hands of the statue were likely replaced at some point, I developed some theories.

Cathedral of Notre Dame, Chartes Cathedral, before 1194 - 13th century. Image courtesy of Artstor

I am of the opinion that the body of The Falconer looks most like the average dress for a 12th Century, non-Nobleman. I am also deliberately overlooking the decoration and coloring of the clothing, as it was likely repainted several times. That date contrasts with his lower extremities, specifically his shoes, as they are like those of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Centuries. Though the shoes are beginning to point, they do not fit trends beyond that period, which is known as the Early Gothic.

Shoe detail of The Falconer, photo taken by Z Stevens

While it is an estimate, the information provided by Barton also suggests that the body of The Falconer does not fit well with the closely fitted, sewed in styles of the Later Gothic Period, or the Fifteenth Century. From this, I now suspect that even if that is when he was made, The Falconer may instead have been meant to look Romanesque, or from the Twelfth Century. His sleeves fit the mid 1100s fashion as wider, exposing the chemise, an undergarment. Barton also mentions that a heavy double sleeve went out by 1200 and would not return until the Renaissance.

Sleeve Detail of The Falconer, photo taken by Z Stevens

A concluding piece of evidence is that The Falconer also wears a Twelfth-Thirteenth Century style chaperon, a hood over the head and neck which connects to a short cape covering the shoulders. The lack of tail on the hood also suggests an earlier date.

Hood Detail of The Falconer, photo taken by Z Stevens

Because of all of these pieces of information from all these parts of the sculpture, I believe that The Falconer was made to look like a man from the mid-Twelfth Century.

Plaque, 1160-1170 CE. Image courtesy of The British Museum

The truth is, even though the torso is the most original part of the sculpture, we will likely never know exactly when it was made. Because of this my final question, while different from the technical one of the dates The Falconer represents, is why would someone recreate a style from history for their sculpture. While there is no one answer to this question, people have always tried to recreate other times and their conventions. Personally, I like to think that The Falconer was meant to be a part of something specific, like a larger work or a story special to the artist or person commissioning it. Maybe he was a shepherd, like the ones on the side of Notre Dame. Whoever he was or was meant to be, it’s very exciting to know that he is at home here at the SCMA.