A Double Take on Edward Hopper

Amanda Shubert is the 2010-2012 Brown Post-Baccalaureate Curatorial Fellow at SCMA.

“The look of a wall or a window is a look into time and space. Windows are symbols. They are openings in. The wall carries its history. What we seek is not the moment alone.” –Robert Henri

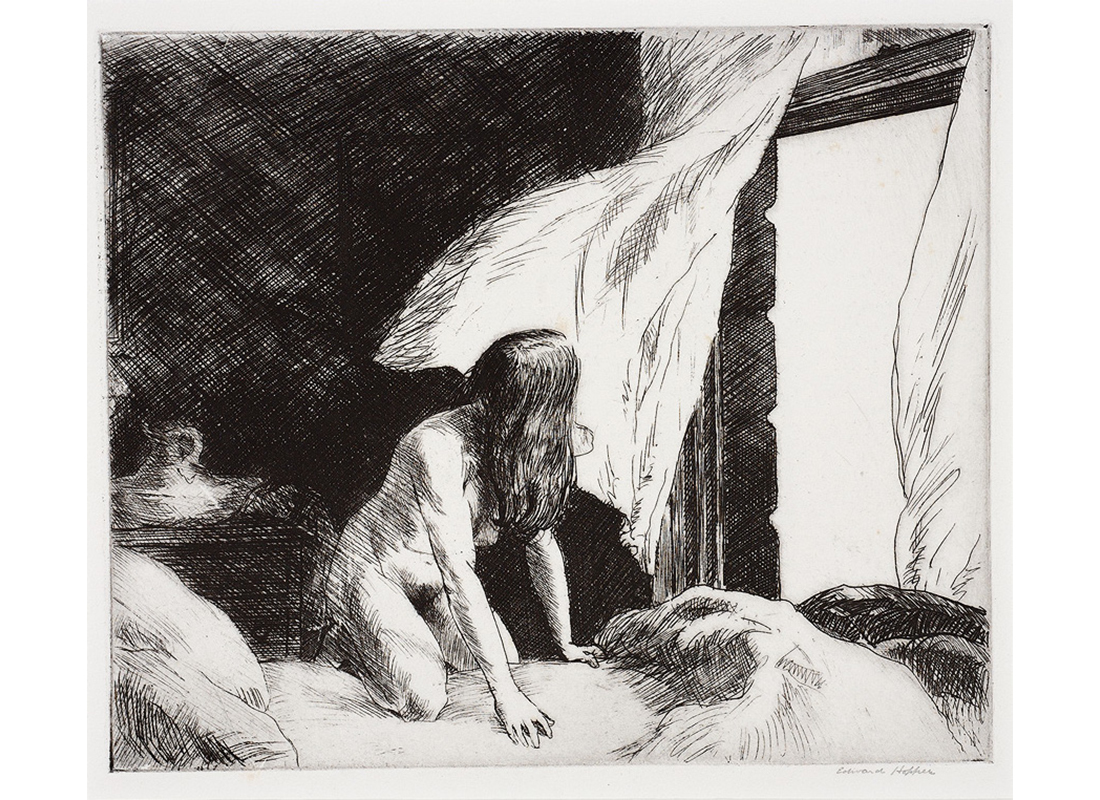

The image above is Evening Wind by Edward Hopper. Best known for his paintings, Hopper began his career as a printmaker, and it is for the extraordinary etchings he produced between 1915 and 1923 that he first gained critical acclaim. His prints, like his paintings, are subtle vignettes of urban experience, rendered with psychological acuity and an eye to formal abstraction. We see solitary nocturnal figures prowling the shadows of empty parks and cafés, and nudes with mask-like faces at the windows of tenement apartments. His etchings are part social record of a time and place, and part portraits of a timeless interiority, a project perhaps best expressed by Hopper’s most frequent and seemingly contradictory claims about his work: that all he is trying to do is “paint sunlight on the side of a house” and that he chooses subjects he believes will be “the best mediums for a synthesis of my inner experience.” In Evening Wind, as in so many of Hopper’s prints and paintings, the way light suffuses a house is a study of inner experience.

Hopper was part of the same generation of printmakers as George Bellows and John Sloan—all three studied at the Art Students League in New York City with Robert Henri, who encouraged them to go out into the city and make quick sketches from memory of what they saw there. Popularly known as the Ashcan School, they were notorious for their crude urban realism.

Consider this etching Turning Out the Light from Sloan’s series “New York City Life”:

John Sloan. American, 1871–1951. Turning Out the Light, 1905. Etching. Courtesy of Connecticut Valley’s Wetmore Print Collection.

This print is is likely a source for Hopper’s Evening Wind. They share a subject – a woman getting into bed at the end of the day – and they are compositionally similar, both illuminated by a single dramatic light source that cuts, like the line of the women’s bodies, diagonally across the print. Sloan’s work, which was rejected from the American Water Color Society in 1906 for its “vulgarity,” shows a woman in the playful euphemistic act of turning out the light; she glances over her shoulder at her lover, and begins to peel down the strap of her nightgown.

Evening Wind is similarly sexually charged, but where Sloan’s print is narrative - and thereby perhaps even more scandalous for the time, asking us to imagine what comes next—Hopper’s is more ambiguous. What has this woman stopped to see? What is she thinking about? The light from the window (mysteriously, since it is evening) seems to symbolize something, but it’s not clear what—it is suggestive, but it can’t be pinned down. And Hopper’s subject, instead of sharing a knowing look with another person, is fixated on the window. She might be watching a lover leave her apartment, or she might just be surprised by the wind that floods the room and engulfs her body. The uncertainty here is important: we can’t see what she sees. The window is blank to us. It illuminates the print, but obscures its meaning; it casts light on the subject, but conceals the object of her perception. The frame of the window suggests the frame of a painting or print—an image-within-an-image, like the painting hanging on the wall behind the curtain, barely perceptible in the shadows – but it’s a private vision, an image only this woman can see.

Sloan’s subject, as his title indicates, is “New York City Life.” The label applies nicely to Hopper’s work as well, but, then again, in Evening Wind, isn’t New York City life precisely what Hopper doesn’t show? It’s what’s happening out in the street - the cars and buses, pedestrians and sidewalks, the urban drama the young woman gazes out at, the area of the print that remains unetched and wiped clean of ink. You might say that Hopper’s vignette of New York City life is a woman looking at a vignette of New York City life. He turns the Sloanian social record, like the light, into an interior experience.