Drawing Dance

Guest blogger Maggie Hoot '16 was a Smith College student, class of 2016, with a major in Art History and a Museums Concentration. She was a Student Assistant in the Cunningham Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings and Photographs.

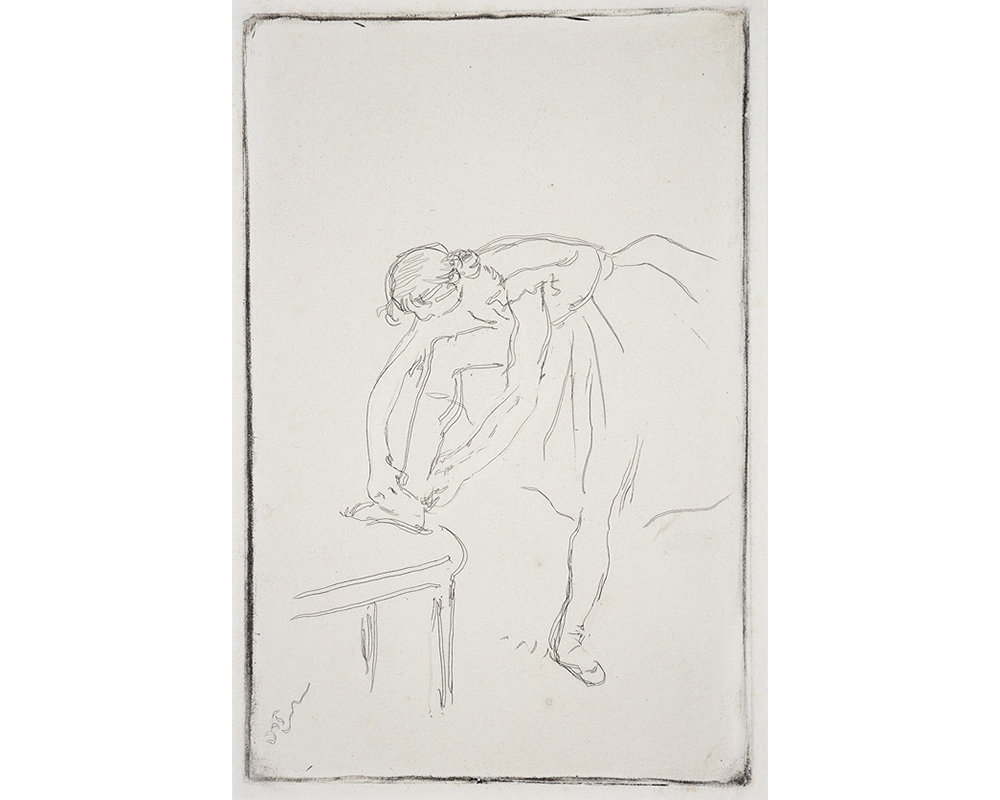

“Writing about music is like dancing about architecture.” There are variations on this quote, but the concept stands: one artistic method cannot be used to interpret another. But is that true? Can the auditory be shared visually? Can an expression of motion be rendered in static form? The idea of conveying messages across expressive media has challenged generations of artists. One of the most prevalent manifestations is the connection between art and dance. Edgar Degas frequently depicted dancers in his art, but his art often focused on the quiet moments before the action.

However, when trying to draw motion, artists approach the task differently, depending on their style and the elements they wish to capture. Artists have attempted to strike a balance between their representation of the dancer and the concept of dance itself.

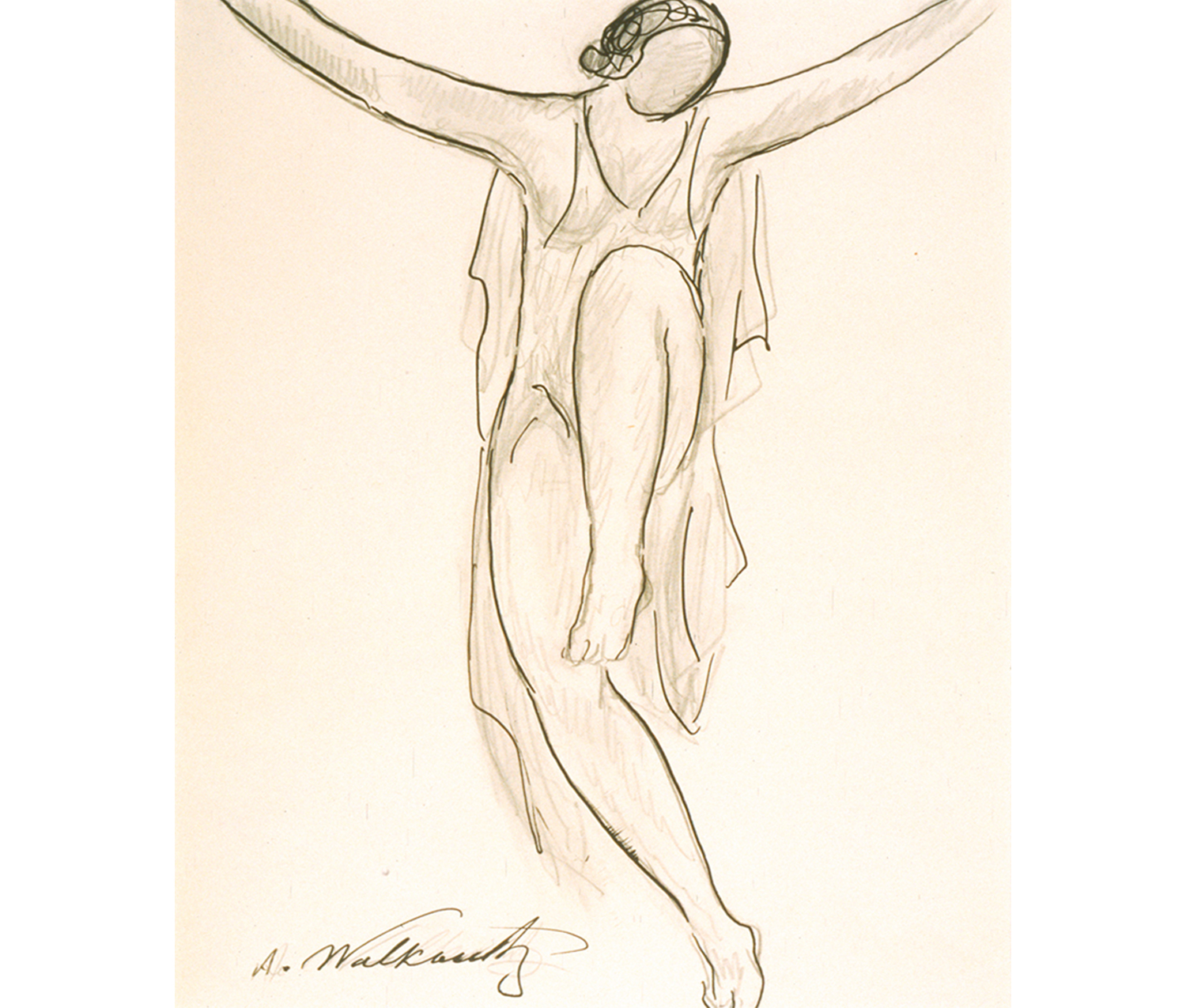

Abraham Walkowitz. American, 1880–1965. Isadora Duncan, n.d. Pen, ink and pencil on off white wove paper. Gift of Abraham Walkowitz. SC 1953.49.6.

Abraham Walkowitz embraced a quick and light feeling in his use of loose pen strokes, evocative of the new modern dance developed by Isadora Duncan. Walkowitz was especially intrigued by Duncan: “Isadora is movement. I watched her dances, and I never had her pose, I just watched the movement, that's what makes the dance the feeling, the movement, the grace" [1].

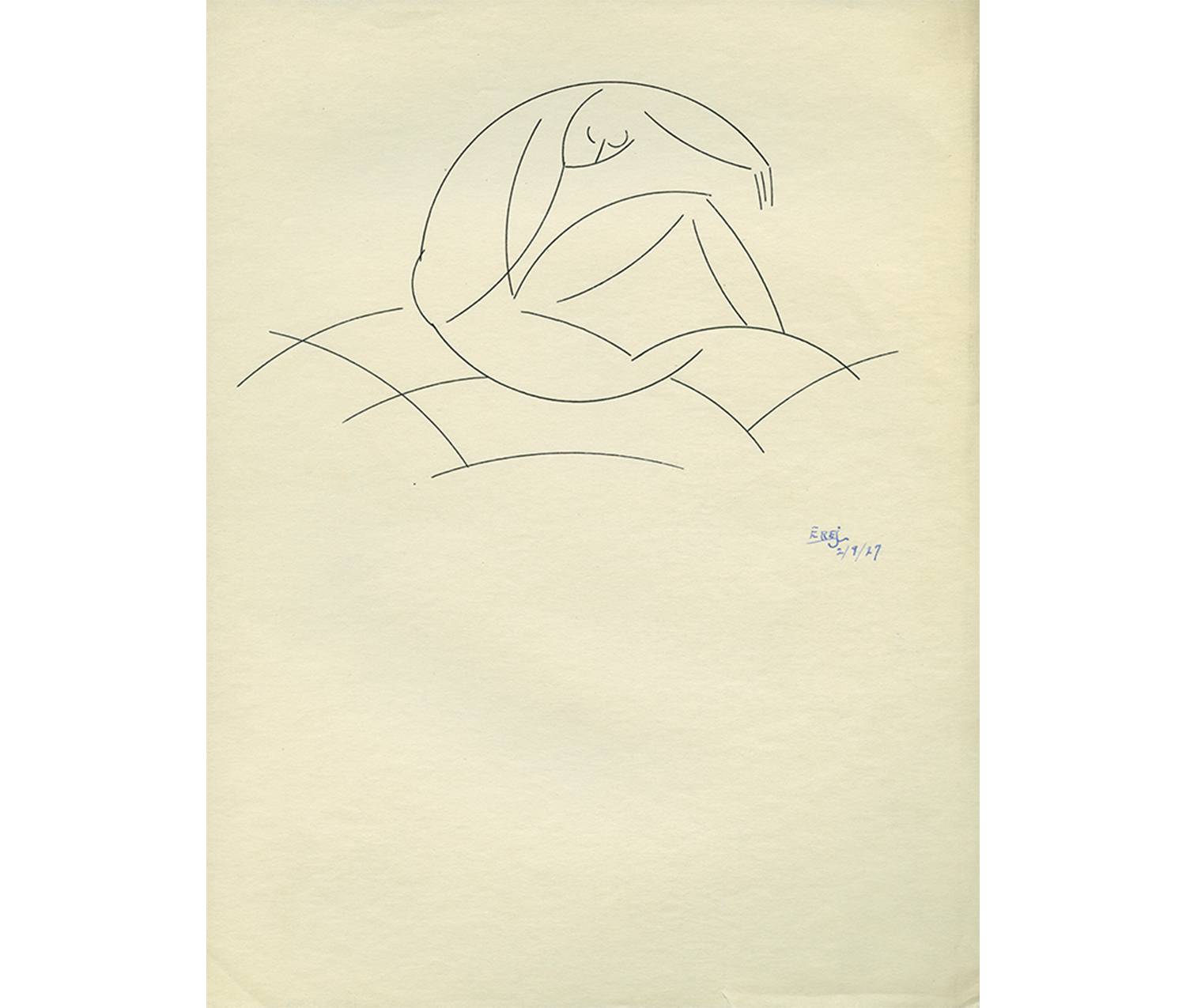

Jere Abbott. American, 1897–1982. Geometric Dancing Figure, n.d. Pen and ink on paper. Gift of Jere Abbott. SC 1979.1.33.

Contrasting the looseness of Walkowitz’s drawings, Jere Abbott refined the lines of the dancer into discrete geometric arcs and angles. While the viewer’s eye is drawn through the circles, the figure itself is more representative of form than motion.

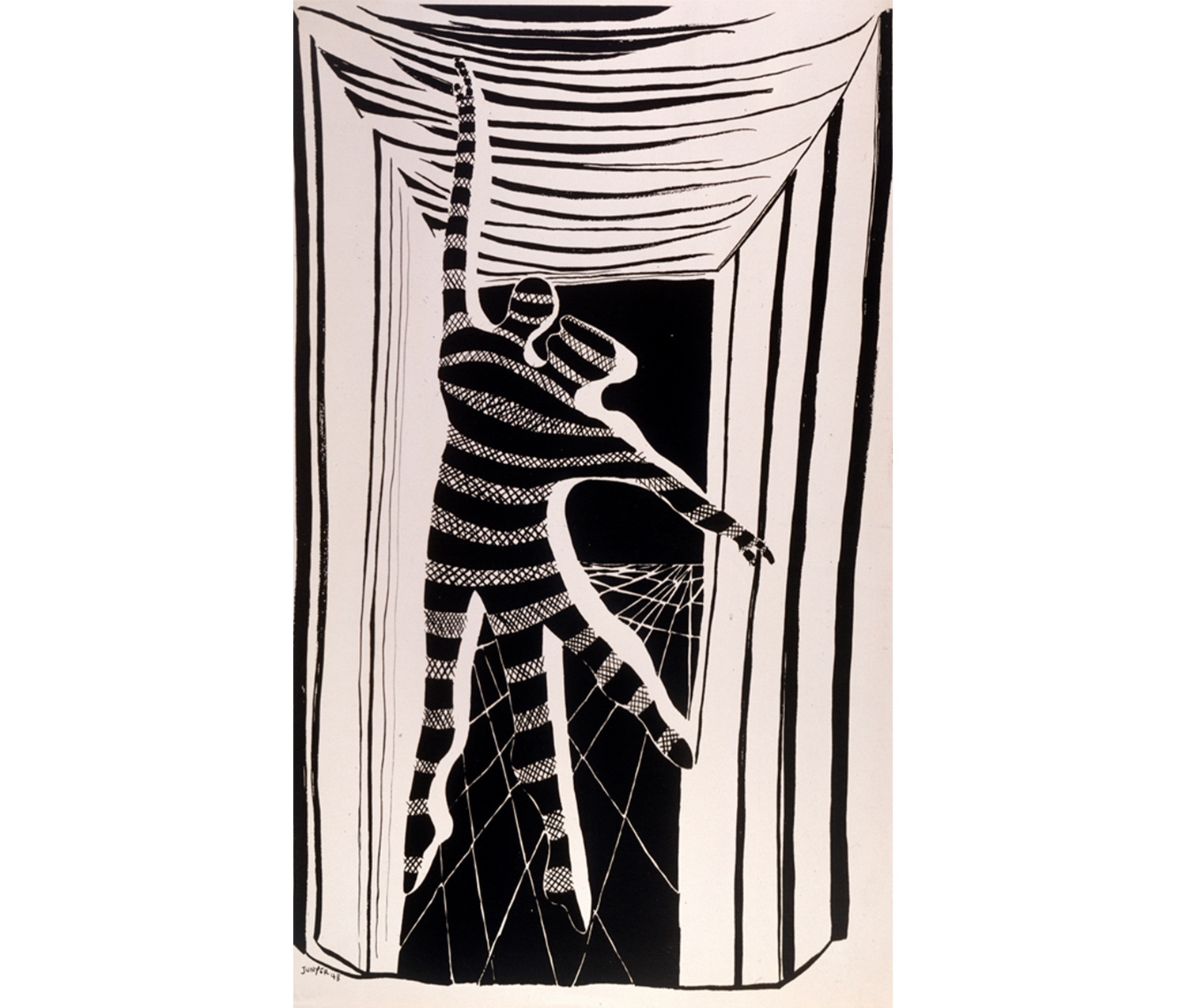

Joan Junyer Pascual-Fibla. Spanish, 1904–1989. Dancers, 1938. Lithograph on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred H. Barr Jr. in memory of Ruth Wedgwood Kennedy. SC 1969.19.

Joan Junyer Pascual-Fibla played with the concept of positive and negative space, giving the background as much agency as the dancers themselves. Also, because the figures seem suspended in midair, they hold a great deal of potential energy-- the possibility of motion.

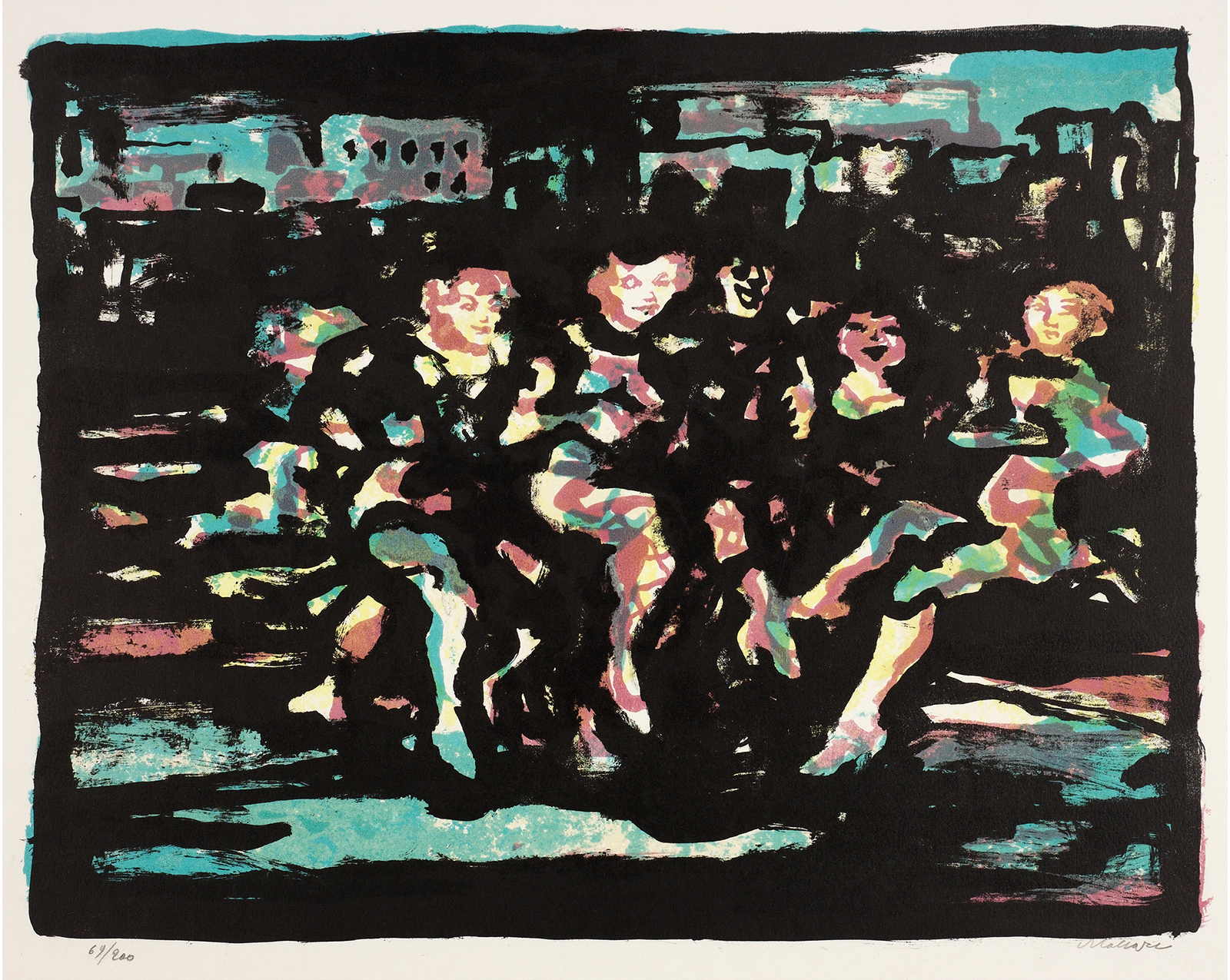

Mino Maccari. Italian, 1898–1989. Dancing Figures, n.d. Lithograph printed in color on paper. Gift of Priscilla Paine Van der Poel, class of 1928. SC 1977.32.177.

In Mino Maccari’s print, the dancers appear to be stepping out of the dark background, adding color and motion to the composition. Only isolated parts of their bodies are visible, but their forms dominate the image.

These four works are only the tip of the iceberg; Walkowitz alone drew Isadora Duncan approximately five thousand times. The challenge of making a static drawing feel dynamic and active has engaged artists for centuries.

[1] Oral history interview with Abraham Walkowitz, 1958 December 8-22, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.