Edvard Munch in Prints

Henriette Kets de Vries is the Manager of the Cunningham Center for Prints, Drawings and Photographs and Assistant Curator of Prints, Drawings and Photographs at SCMA.

The Smith College Museum of Art is dedicated to bringing out works on paper into the main galleries, where all visitors can see them. Since works on paper are more sensitive to light than other mediums, SCMA has installed special Works on Paper cabinets throughout the galleries for the display of prints, drawings and photographs. Today’s post is part of a series about the current installations of the Works on Paper cabinets, which will remain on view through April 2017.

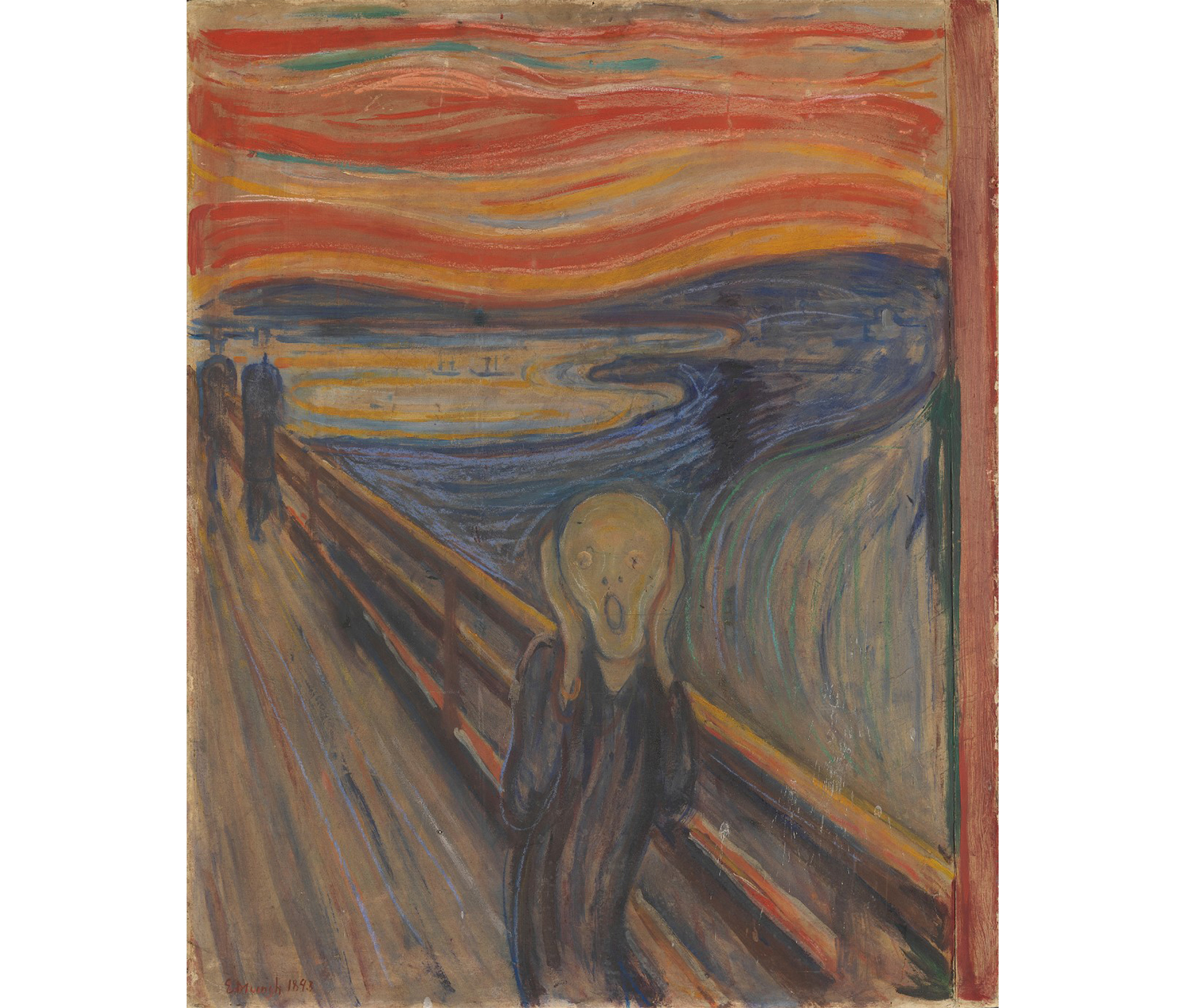

Given the new interest in human psychology spurred by Sigmund Freud in the late nineteenth century, introspective art like the work by Edvard Munch (1863–1944) tapped directly into a new cultural awareness and exposed the hypocrisy of polite society. This new understanding of the human psyche led to a growing appreciation of Munch’s work, especially in more urban modernist environments like Berlin and Paris. As Munch said of his work, “I paint not what I see but what I saw.” His artwork became a direct outlet for suppressed emotions and anxiety, touching upon the darker side of human consciousness as his most famous painting The Scream attests.

The Scream, 1893, National Gallery, Oslo, Norway.

Edvard Munch’s life was overcast with sickness, death, and mental instability. Born into a devout, cultured family in Norway, Munch lost both his beloved mother and eldest sister to tuberculosis at an early age and was raised by his obsessively religious and anxious father. The artist was plagued with bouts of melancholy and depression throughout his life and later battled alcoholism.

Munch’s success was hard-fought; his contemporaries in Norway originally rejected his psychological “realism” and attacked his lack of technical ability, criticizing his disregard for what they considered to be “good form.” They dismissed his work as “sick” and “an insult to art.”

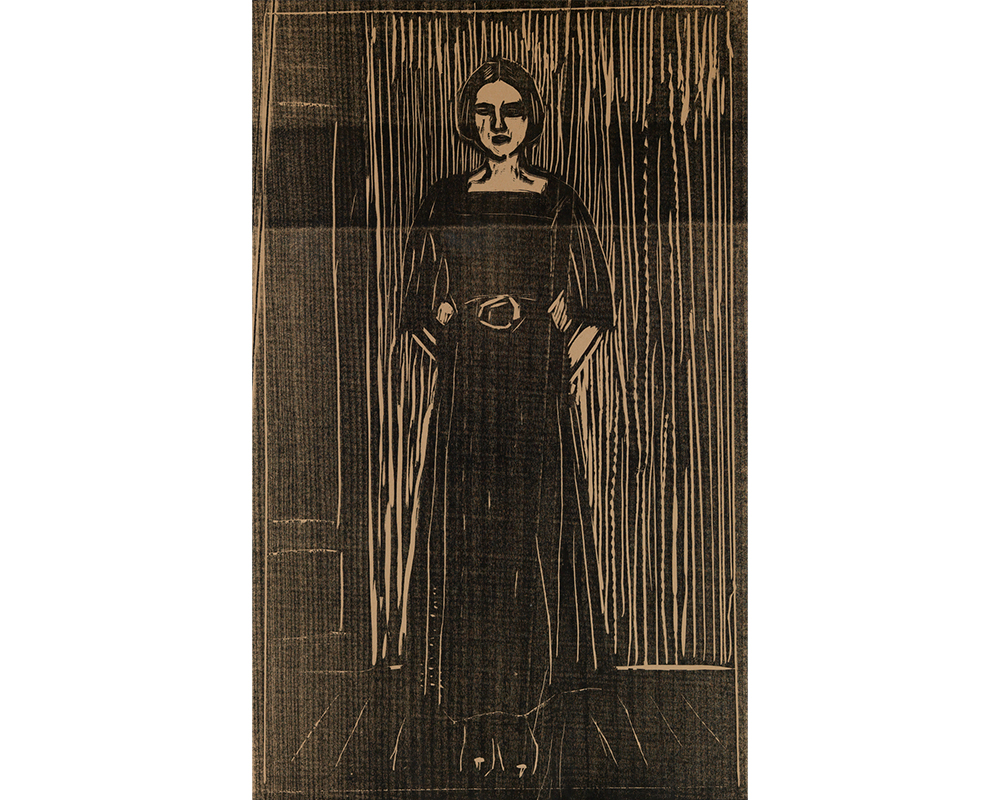

Even though most of Munch’s work stems directly from the artist’s own troubled psyche, not all his work was autobiographical. Raised on literature, art, and music, Munch, like his father, was a great story teller, who wrote poetry and illustrated books and plays. Although originally ostracized by most of his fellow Norwegians, who rejected his work, he found a kindred spirit in the Norwegian playwright Henrik Ibsen, who personally encouraged Munch during one of his poorly-received exhibitions in Norway. Munch illustrated many of Ibsen’s plays, which, like Munch’s art, addressed societal hypocrisy and complex human emotions.

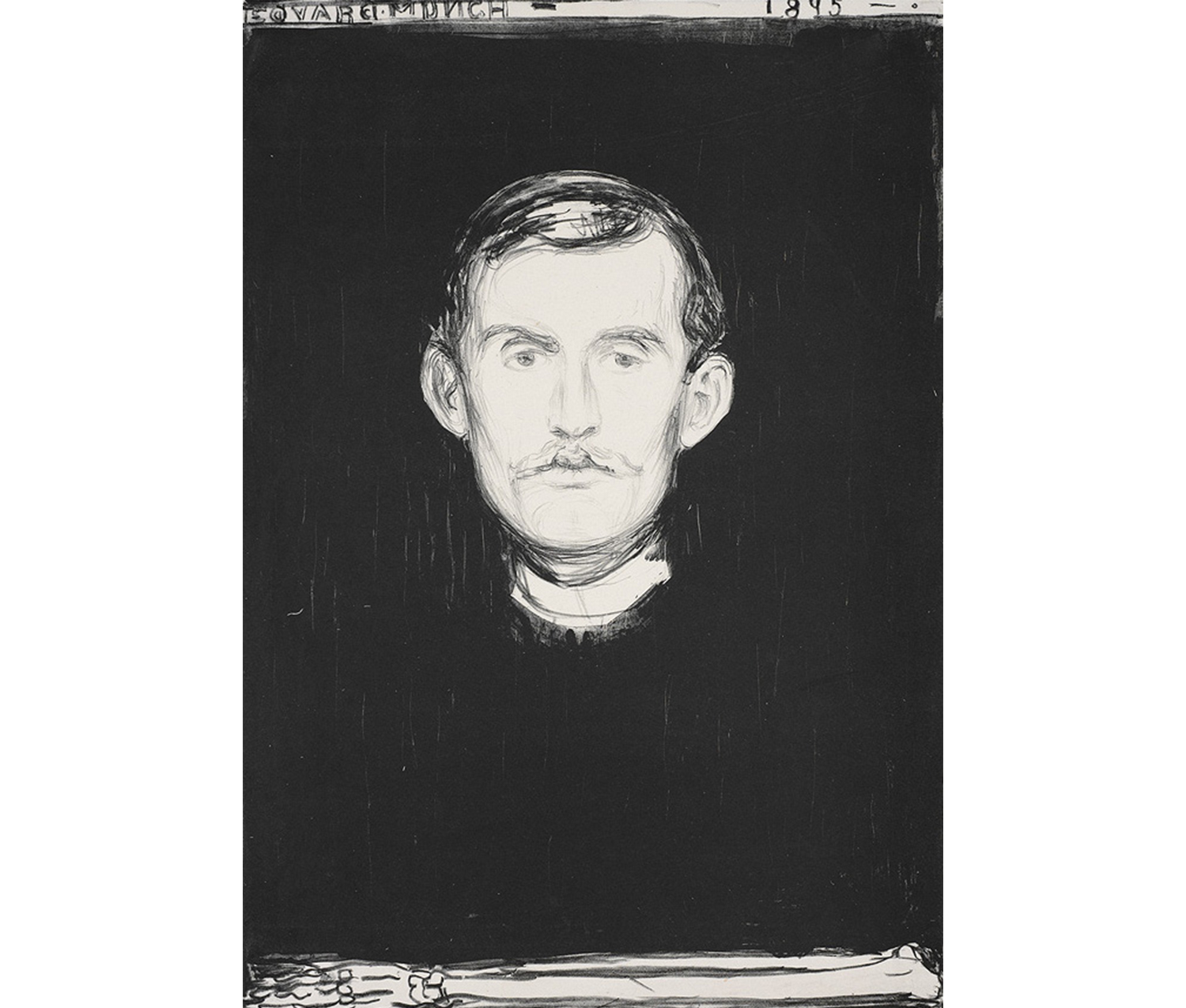

As the famous art critic Robert Hughes said of Munch’s self-portraits, “It is hardly surprising that someone as miserable and self-obsessed as Munch should have painted so many self-portraits.” The artist suffered from an unhappy childhood and seemed unable to escape the overriding gloom that dogged his life. His relationship to “his children”—as he called his artworks—as well as his own personal angst, affected his ability to have normal interactions with people, especially with women. Munch became his own, best subject, obsessively recorded in hundreds of self-portraits, including the famous painting, The Scream. Each of these images captured a different aspect of Munch’s troubled psyche.

Edvard Munch. Norwegian, 1863–1944. Self-Portrait with Skeleton Arm, 1895. Lithograph with crayon, tusche, and needle on paper. Purchased. SC 1969.75.

Munch’s first print was this early Self-Portrait with Skeletal Arm, created when he was 31 years old and living in Berlin. Beautiful in its simplicity and seemingly devoid of emotion, the pallid face rises from the black background. The simple skeletal arm at its base, however, evokes complex feelings. The use of a skeleton within a self-portrait, in combination with the inscription at the top, harkens back to memento mori (Renaissance portraits with skulls). The sitter’s contemplative stillness, surrounded by a black void, could therefore be interpreted as Munch’s acceptance of the inevitable end of life.

Edvard Munch. Norwegian, 1863–1944. Printed by Otto Felsing. German, 1854–1920s. Christiana-Bohême I, 1895. Etching and drypoint printed in black on wove paper. Gift of Selma Erving, class of 1927. SC 1972.50.69.

This print depicts a group of Munch’s friends drinking absinthe and wine during one of their many gatherings. They represent Christiania Bohème, the Bohemian atheistic, anarchist movement of the 1880s in Oslo (formerly called Christiania) that promoted free love, modernist art, and literature. Playwright Henrik Ibsen was a major figure in the movement, but at that point had already been living abroad for sixteen years. Munch’s friend and mentor Hans Jäger was the group’s leader; his autobiographical novel From Christiania’s Bohemia gave the movement its name.The print lacks the usual anxiety of Munch’s other works even though some undefined dark shadows are looming behind the seated figures at the right. The casual expressions on their faces suggests an amicable assembly of kindred spirits.