Embracing the Enemy

Maggie Kurkoski is a member of the Smith College class of 2012 and the Brown Post-Baccalaureate Curatorial Fellow in the Cunningham Center.

The Smith College Museum of Art is dedicated to bringing out works on paper into the main galleries, where all visitors can see them. Since works on paper are more sensitive to light than other mediums, SCMA has installed special Works on Paper cabinets throughout the galleries for the display of prints, drawings and photographs. Today’s post is part of a series about the current installations of the Works on Paper cabinets, which will remain on view through April 2015.

Smith College is home to the Mortimer Rare Book Room, which takes care of our literary manuscripts and rare books. Sometimes, though, a book finds its home in the Cunningham Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings and Photographs. Such is the case with Prométhée, a livre d'artiste with a star-studded pedigree.

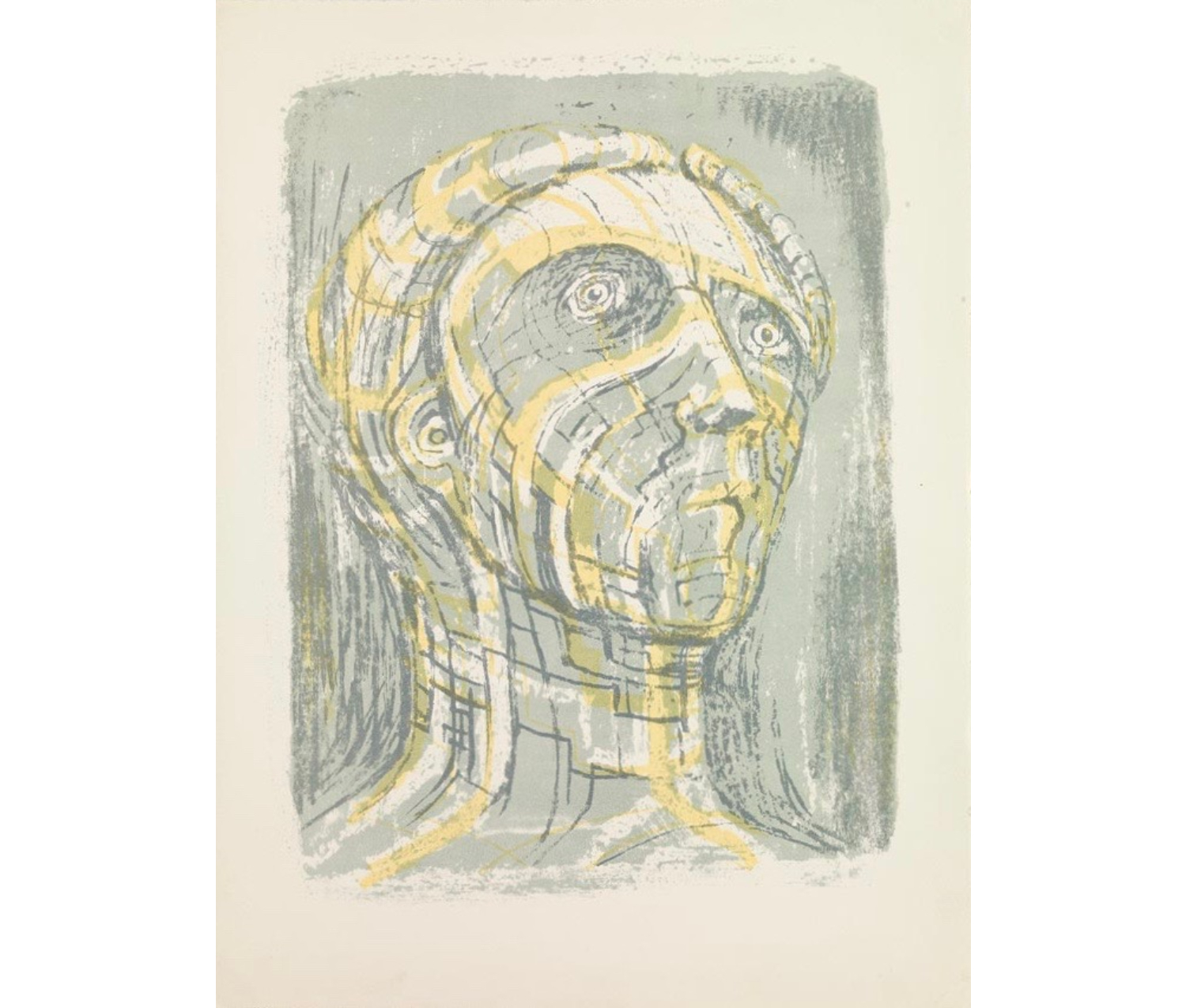

Henry Spencer Moore. English, 1898–1986. Prométhée; Head of Prometheus, 1950. Lithograph on paper. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1951.277.3.

The story told in Prométhée emerges from the sprawling mythology of Ancient Greece and revolves around Prometheus, a powerful being who is infamous for one crime: he stole fire from Zeus and gave it to humanity. In some stories, Prometheus is also the creator of humankind, whom he sculpts out of clay. Perhaps the most famous rendition of his story is the ancient tragedy Prometheus Bound in which (as one might guess from the title) Prometheus spends the entire play chained to a rock in punishment for his transgressions.

German writer Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749–1832) was fascinated by this age-old myth. A major player in the Sturm und Drang literary movement, which celebrated the power and emotions of the individual, Goethe saw Prometheus as a courageous rebel who fought against the tyranny of Zeus’ rule. Throughout his life Goethe began three different Prometheus plays, but he never completed any of them. Interestingly, he never depicts Prometheus as chained, in sharp contrast to Prometheus Bound.

One fragment by Goethe was later translated into French by André Gide (1869–1951), who titled his translation Prométhée.

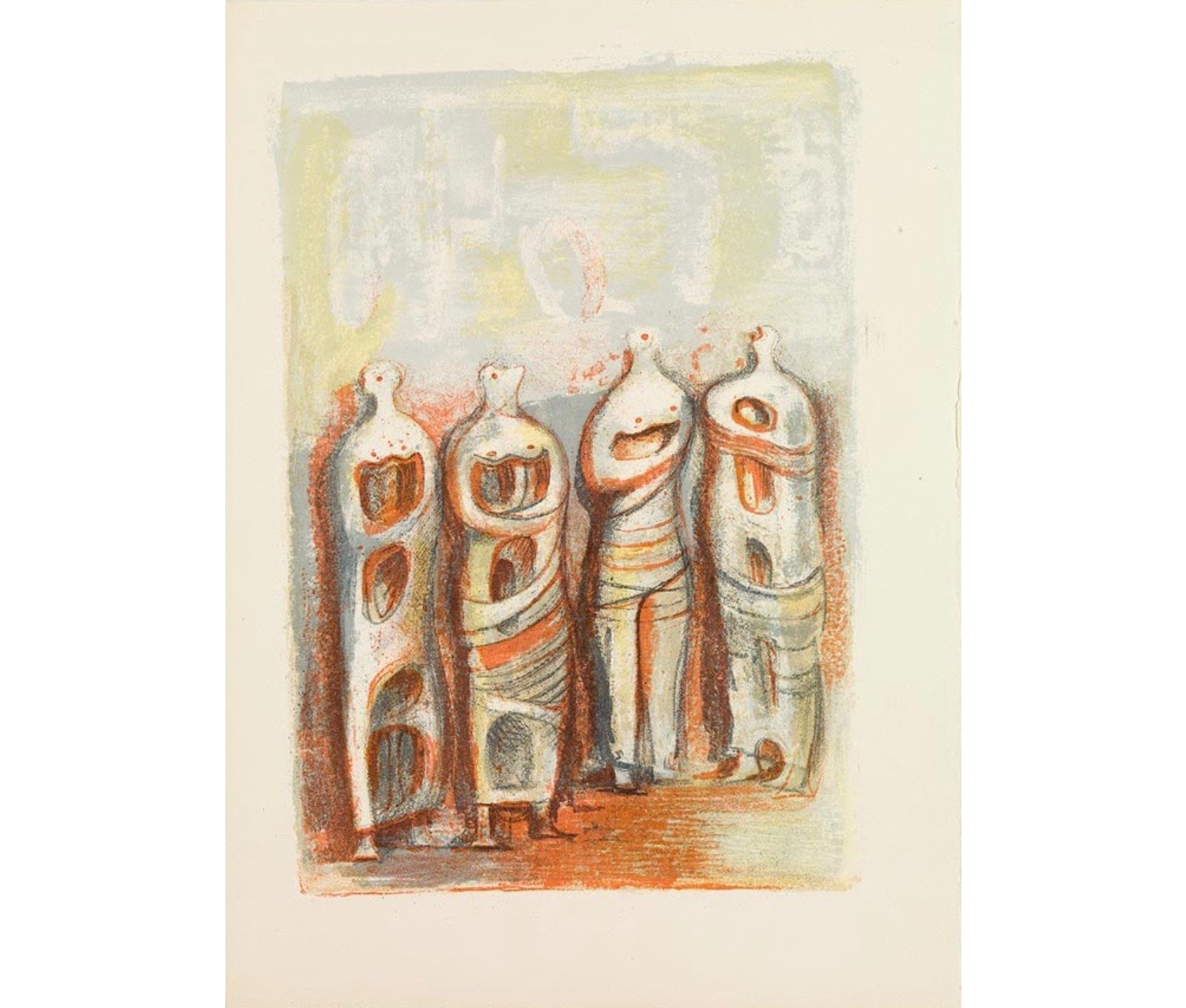

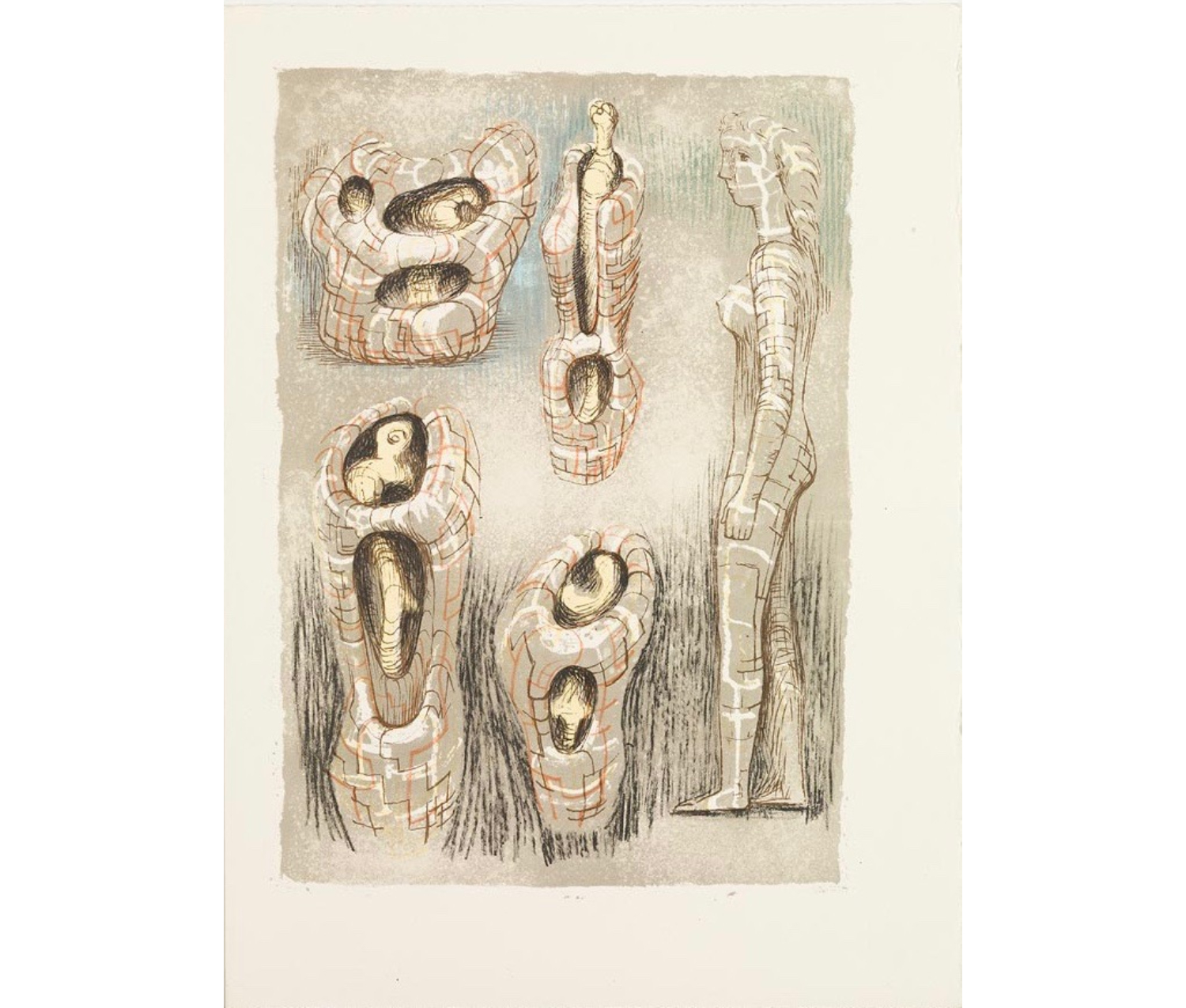

Henry Spencer Moore, English, 1898–1986. Prométhée; Four Statuettes, 1950. Lithograph on paper. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1951.277.4.

In December 1949, near the end of Gide’s life, the British artist Henry Moore was visiting Paris, and it was on this trip that Moore met Henri Paul Jonquières. Although Moore is most famous for his monumental abstract sculpture, the French publisher and typographer proposed that the two men turn Gide’s translation into a livre d’artiste, or artist’s book, and Moore agreed to illustrate it. Ultimately, Moore produced eight full-page lithographs and multiple design elements for Prométhée, which became his first graphic book.

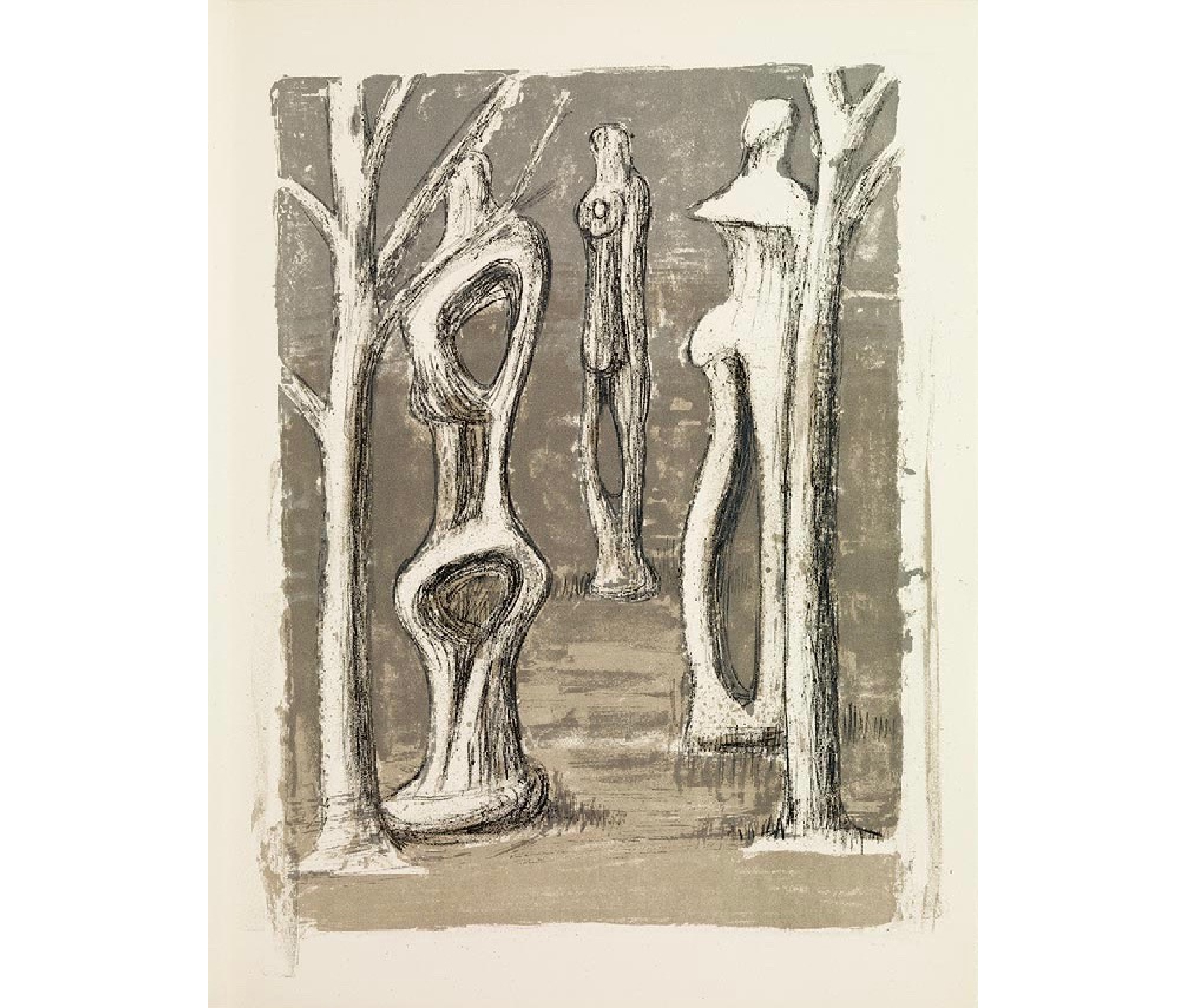

Henry Spencer Moore. English, 1898–1986. Promethée; Prometheus Instructing Another to Build Shelter, 1950. Lithograph on paper. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1951.277.9.

Moore’s choice to illustrate a narrative story may surprise those who are familiar with his sculpture, which is best described as semi-abstract – more Cycladic figurine than Hellenistic Bronze. Early in his career, Moore rejected the dogma asserting that art needed to emulate famous Classical masterpieces: “I thought that the Greek and the Renaissance were the enemy, and that one had to throw all that over and start again from the beginning.”

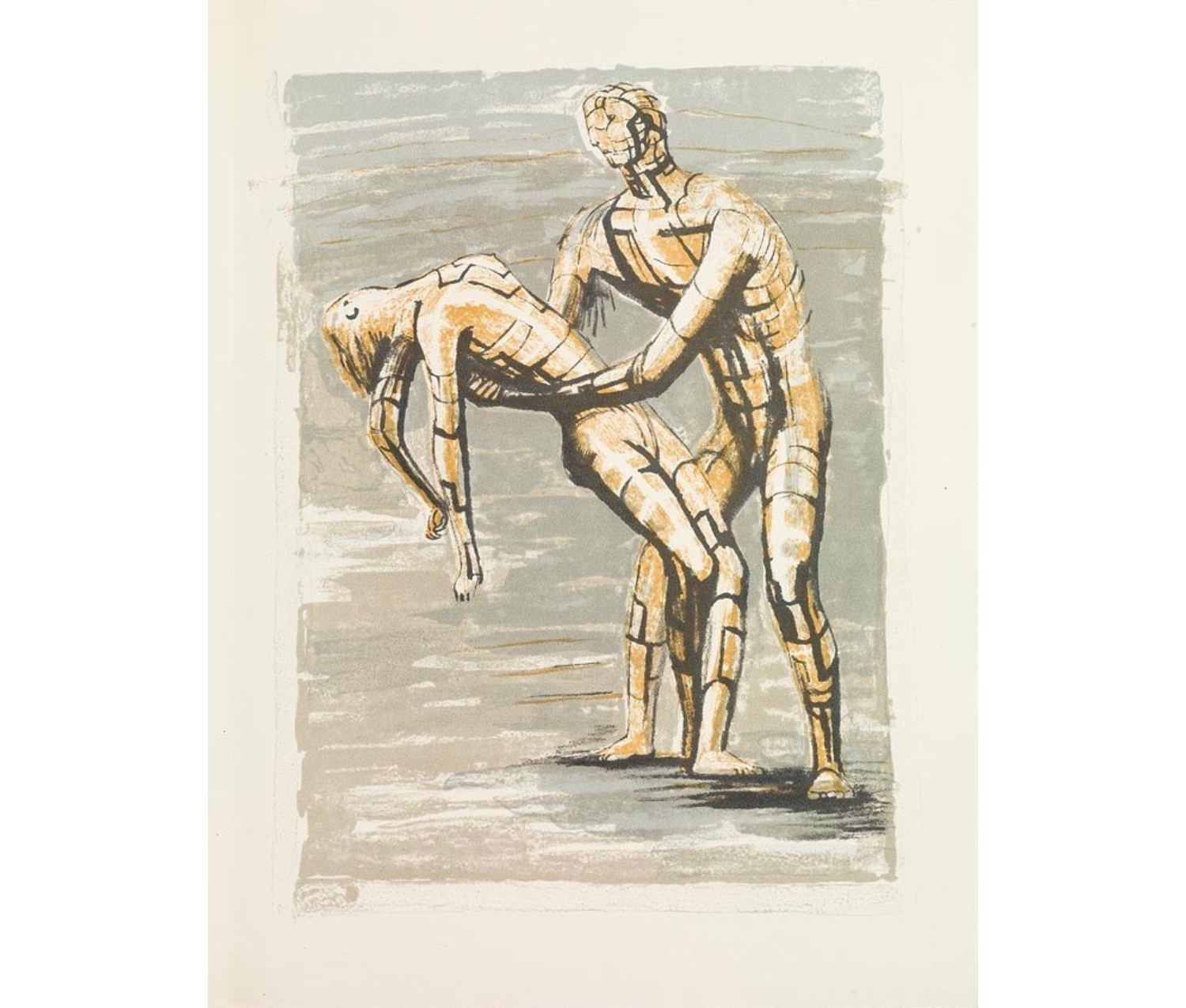

After the end of World War II, however, he began to experiment with traditional Greek literature and, eventually, some visual motifs from the Classical era. This shift is evident in both the subject matter and illustrations of Prométhée. Although Moore’s lithographs are grounded in his typical style, with its rounded abstract shapes and bold forms, certain elements emerge from ancient art.

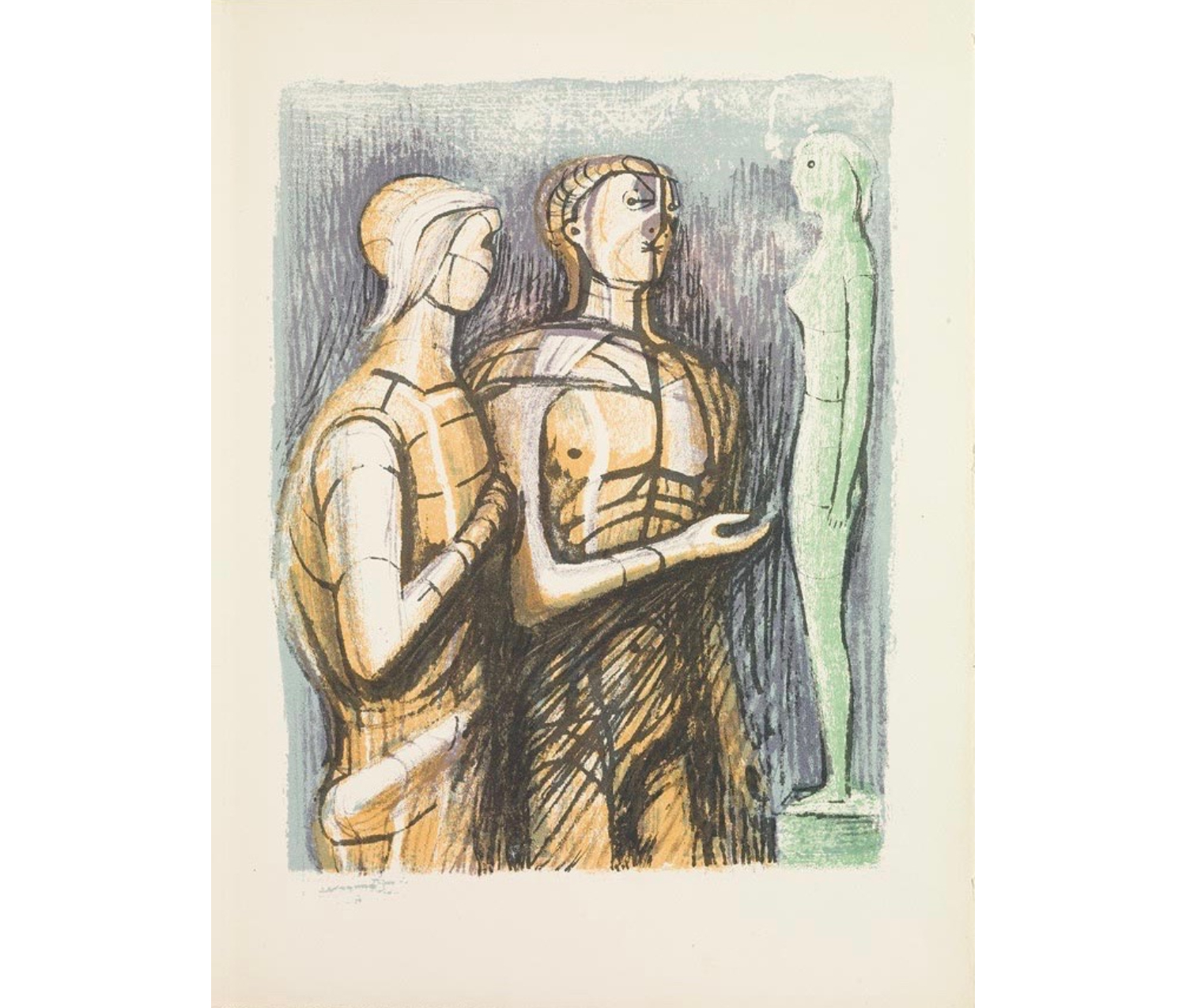

Henry Spencer Moore. English, 1898–1986. Prométhée; Prometheus and Minerva Before the Statuette of Pandora, 1950. Lithograph on paper. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1951.277.5.

For example, in the print above, Prometheus and Minerva Before the Statuette of Pandora, Prometheus and Minerva appear unclothed at first, but sweeping strokes along their torsos suggest the thin, draping garments of antiquity. The two look at a statue of Pandora, who resembles in many ways early archaic Greek statues: her pose is forward-facing and static, without the naturalism or contrapposto of later eras. This similarity turns up again in the print Pandora (below), as Pandora stands with her left foot forward, nude, both characteristics of early archaic sculpture.

Henry Spencer Moore. English, 1898 –1986. Prométhée; Pandora, 1950. Lithograph on paper. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1951.277.11.

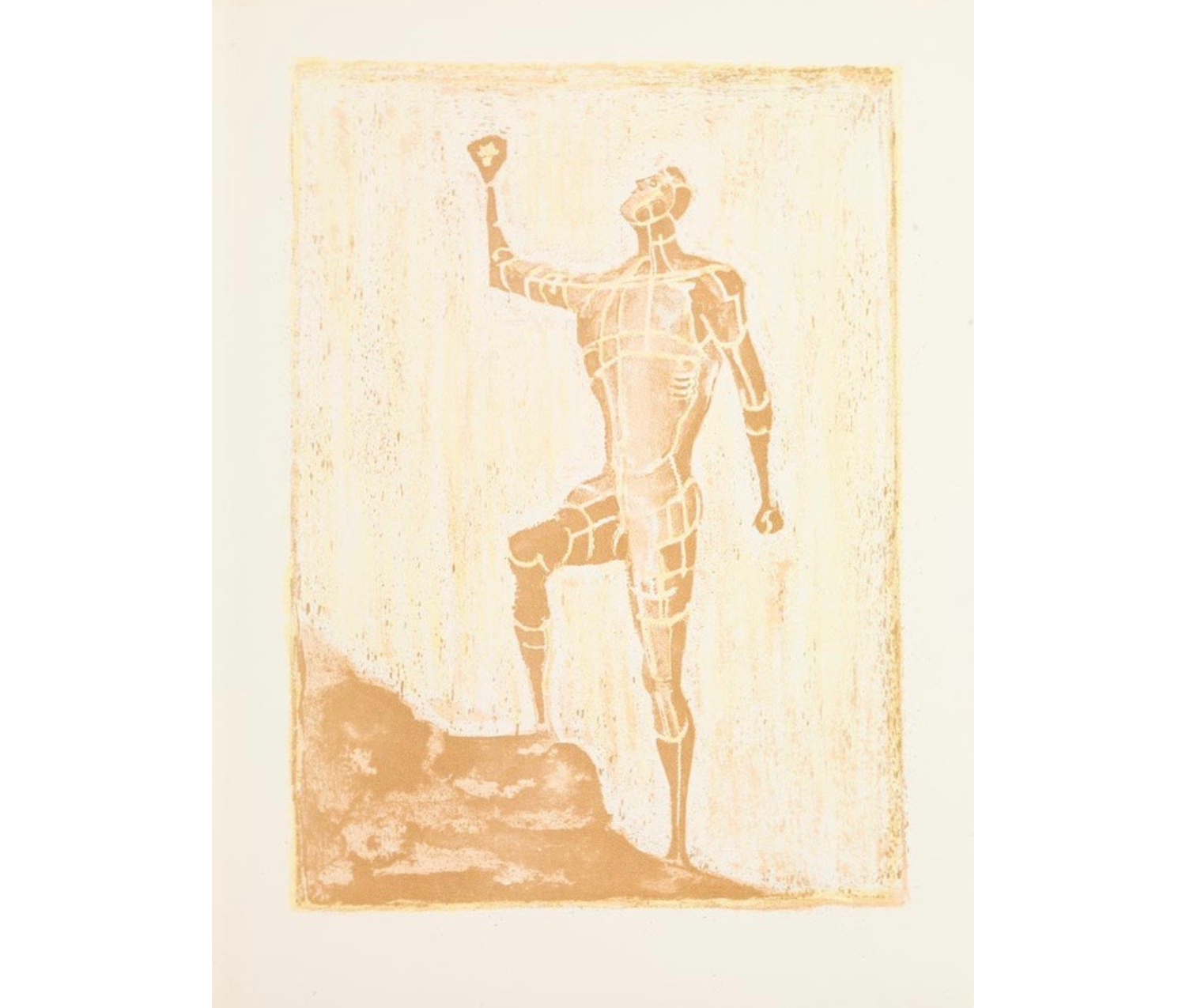

It's possible that the myth of Prometheus held a special resonance for Moore. Prometheus creates mankind from clay, so like Moore, he is a sculptor himself. Moore’s illustrations of Prometheus underscore the mythical character’s nobility and courage, rather than his suffering; he is not the tortured hero chained against the rock, but the strong hero.

Henry Spencer Moore. English, 1898–1986. Prométhée; Prometheus "Couvre Ton ciel O Zeus", 1950. Lithograph on paper. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1951.277.14.

Henry Spencer Moore. English, 1898–1986. Prométhée; Arbar and the Fainting Mira, 1950. Lithograph on paper. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1951.277.10.

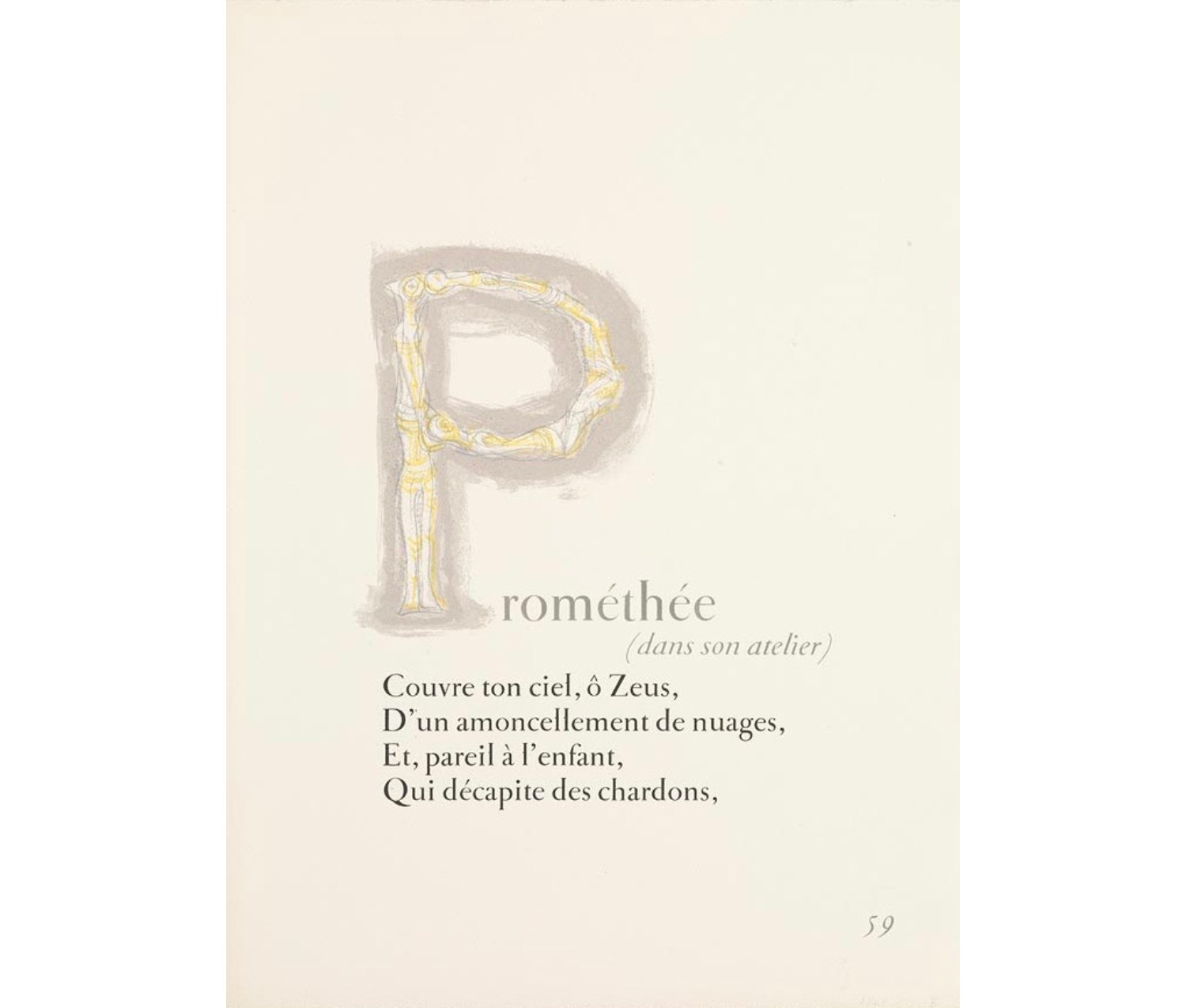

Of course, an artist’s book is more than just its illustrations. One central feature is often overlooked: the appearance of the text itself. For Prométhée, the French typographer Henri Paul Jonquières worked closely with Henry Moore to create a beautiful display of text that would complement the book’s meaning. Jonquières set the text in Romain du Roi, a classic typeface originally made for King Louis XIV. Conceived by the Academy of Sciences, Romain du Roi was envisioned as a scientific typeface, with each individual letter designed in a strict grid, unlike earlier styles based on handwritten models.

Henry Spencer Moore. English, 1898 –1986. Prométhée; Act III, Figured Capital "P", 1950. Lithograph on paper. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1951.277.13.

From the beginning, Jonquières involved Moore in the design of the text. In addition to his full-page illustrations, Moore also created design elements such as the large letters at the start of each act. Jonquières imagined these oversize letters with “sculptural constructions in mind.” Manifesting Jonquières’ vision, Moore created the letters from intertwined human bodies, as seen in the illustrated “P” above. In Prométhée, both typography and illustration come together as a complete work of art.

Henry Spencer Moore. English, 1898–1986. Study for Three Standing Figures in Battersea Park, London, 1946. Bronze. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1951.199.

Prométhée isn’t the only work by Moore in the collection. The Smith College Museum of Art owns Study for Three Standing Figures in Battersea Park, London (shown above), which Moore created in 1946 as a preliminary small bronze study for a monumental public artwork. Much like Prométhée, this work recalls ancient Greece, as it features three female forms in draping garments that resemble ancient attire. Study for Three Standing Figures in Battersea Park, London is currently on view in the third floor gallery.

Want to see Prométhée in person? Selections from this livre d'artiste are currently on view in the Museum, in the second floor Works on Paper cabinet. It will remain on view through April 2015.