1967. Watercolor on thick, rough cream-colored paper. The Carol O. Selle, class of 1954, Drawing Collection. Gift of Carol O. Selle. SC 2020.17.85

Exploring Alfred Leslie: Notan Study for the Killing of Frank O’Hara, 1967

The gift of 142 drawings from the bequest of Carol O. Selle, class of 1954, has transformed SCMA's already outstanding drawing collection. Highlights from this momentous gift will be the subject of a series of posts featured on SCMA Insider. This post, by Aprile Gallant, senior curator of prints, drawings, and photographs, focuses on a drawing by Alfred Leslie.

One of my favorite American works from the Carol O. Selle Drawing Collection is Alfred Leslie’s Notan Study for the Killing of Frank O’Hara, 1967. I was particularly taken with the subtle light effects and economy of means employed in this drawing.

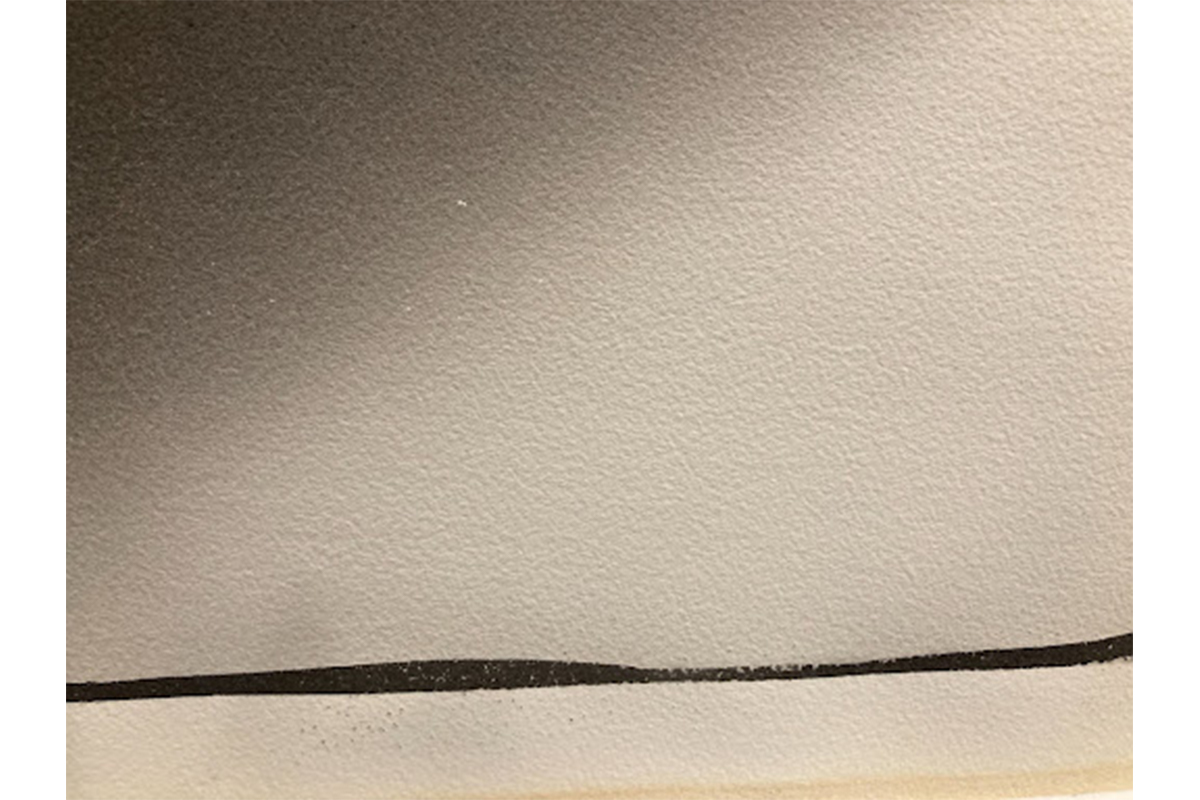

Strong light emanates from the right side—a glow that dominates the lower right corner, accentuating the heavy black line at the bottom and the white band below.

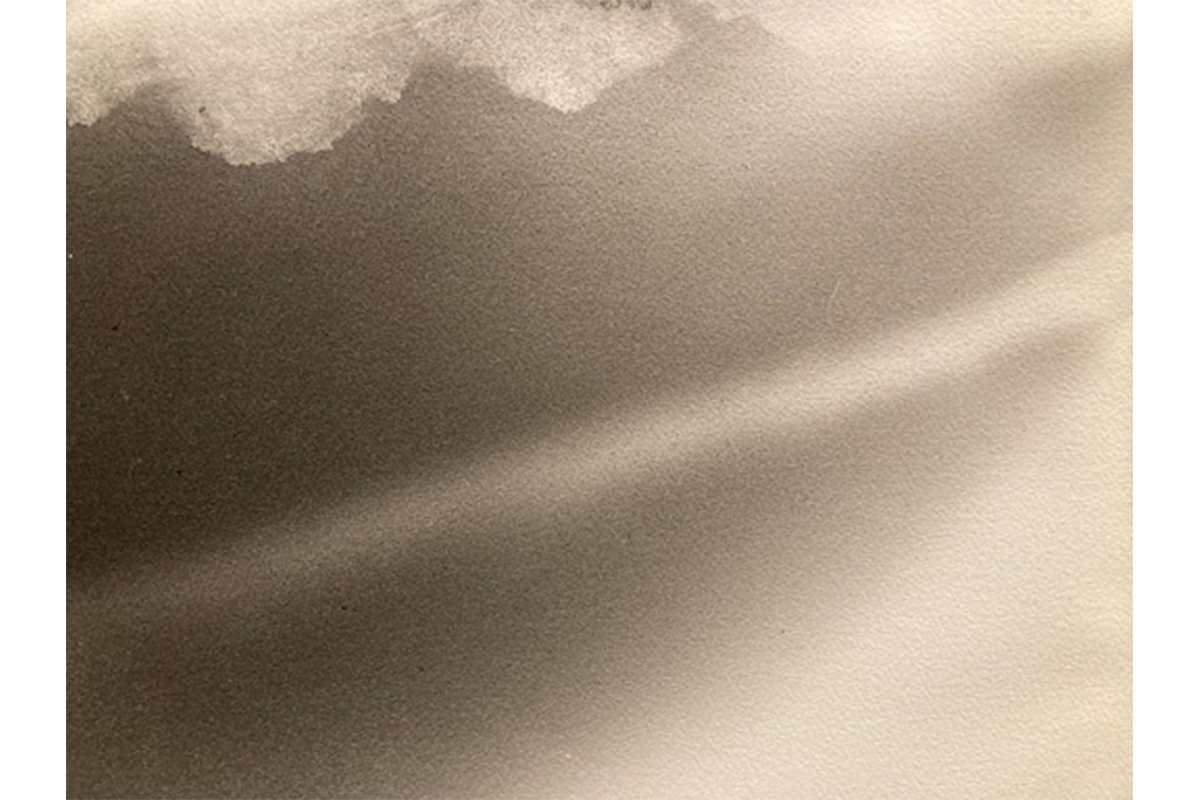

A beam cuts diagonally from right to left, with loosely scumbled clouds hovering above and to the left. Leslie’s use of the paper—a heavy watercolor sheet—as his white adds weight to the light emphasizing the dramatic moodiness.

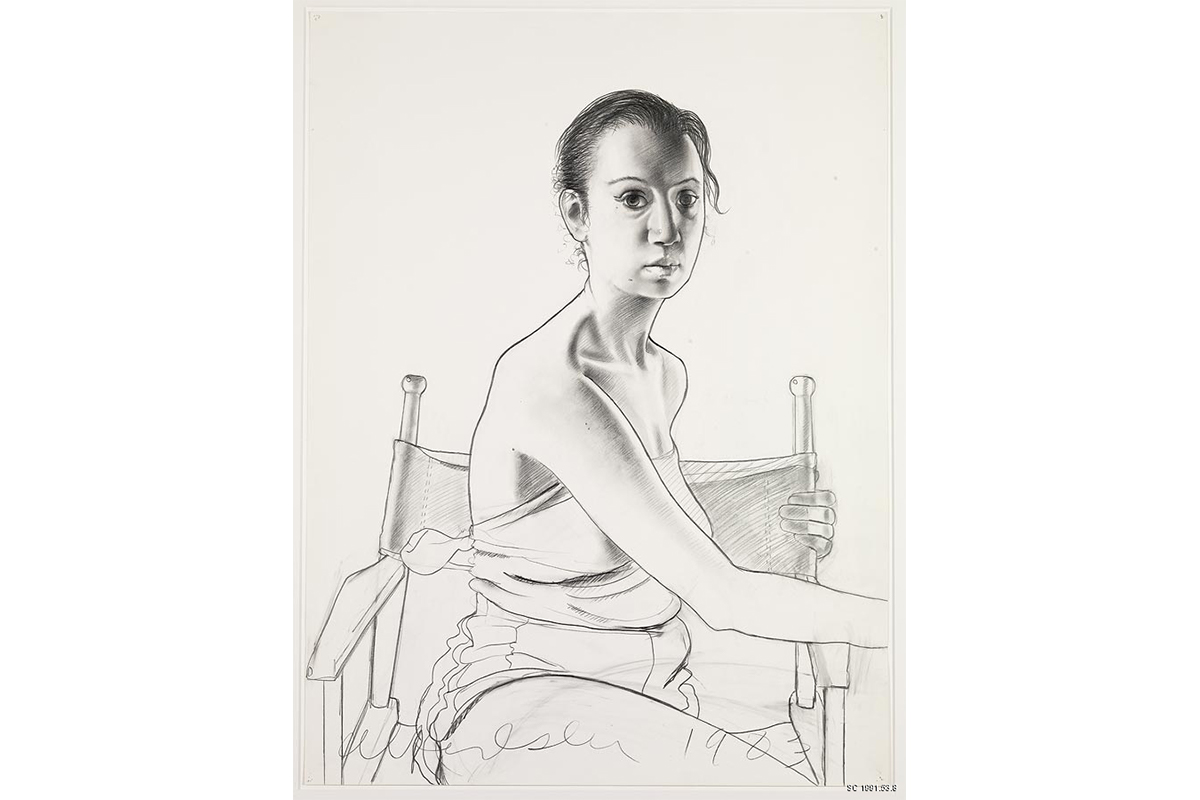

I was also fascinated by the level of abstraction in this work, as I was more familiar with the artist’s figure drawings such as Afternoon Soap, No 3 in the SCMA collection.

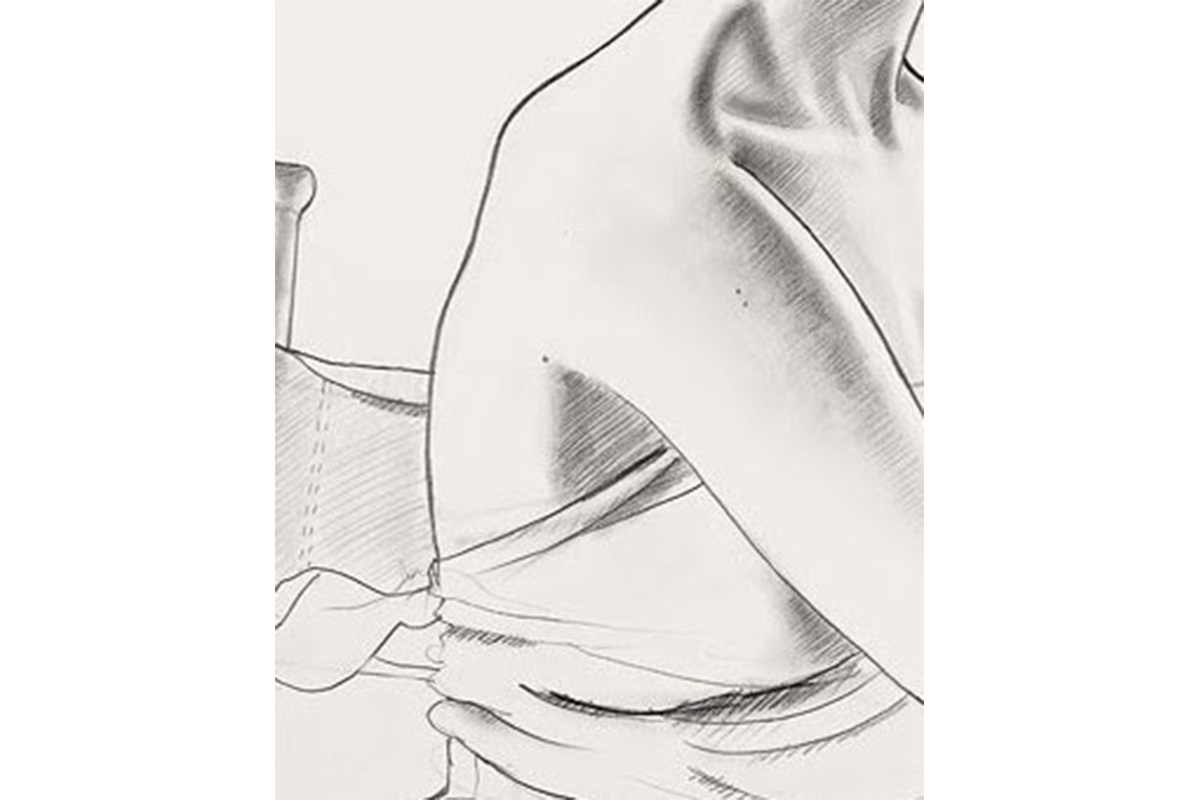

When directly comparing the two drawings, however, it’s easy to see a relationship between them, particularly in the use of light to create dimension and delineate form. Also, while the figure in Afternoon Soap No. 3 reads clearly as three-dimensional, there are many areas (such as the model’s left shoulder) that simultaneously read as flat and rounded. This playing with space through the manipulation of light is a hallmark of Leslie’s work.

Leslie seems to have been literally at the center of avant-garde art in New York from the late 1940s through the early 1970s. Working simultaneously in painting, drawing, collage, and film, he was on the forefront of the transition from abstraction to figuration in American art, and he has continued to push the boundaries between media in his recent digitally-based works.

Exhibiting first as an abstract painter in the 1940s, Leslie’s work was featured in signal exhibitions such as “New Talent,” for which he was selected by Meyer Schapiro and Clement Greenberg at the Koontz Gallery in 1949, and “16 Americans,” curated at the Museum of Modern Art by Dorothy Miller (Smith class of 1925) in 1959. He also made films, including “Pull My Daisy” (1959). Considered a signal expression of Beat-era aesthetics, the film is a collaboration with photographer Robert Frank featuring Alan Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, Larry Rivers, and other American cultural figures.

In the early 1960s Leslie pivoted from creating the abstract paintings for which he was well known to large-scale figurative works distinguished by their scale, monochrome palette, and dramatic lighting. The Whitney Museum of American Art planned a major exhibition of Leslie’s new work for the fall of 1966; however, in October, a fire destroyed the artist’s home/studio, with 12 firefighters killed in the process of battling the blaze. Most of the paintings to have been featured at the Whitney were lost, and the show was cancelled.

This wasn’t the only tragedy to befall Leslie that year: In the summer of 1966, Leslie’s friend and frequent collaborator, the poet Frank O’Hara, was killed after being hit by a jeep on the beach Fire Island. These devastating events prompted the artist to begin work on a series of paintings called The Killing Cycle, which preoccupied him for over the next two decades.

In the summer of 1967 Leslie rented a house on the beach in East Hampton on Long Island specifically to make landscape studies for The Killing Cycle. Working in monochrome watercolor, he completed 30 sheets focused on light and the juncture of sky, water, and land. Leslie called these drawings “Notans” based on his understanding of the Japanese concept of nōtan as “the belief that there can be an eternal unchanging response to the certain beauty of just so much white to just so much black.” He saw the term as “both descriptive and judgemental, bespeaking both style and quality. It is a noun and a verb.”

It is surprising to me that Carol Selle acquired this work, as most of the drawings she was buying at the time were of figures rather than landscapes, and were more finished and detailed than loose and atmospheric. Selle’s record book indicates that she purchased two drawings from the Notan series in 1967, although an inscription by Leslie on the back of the drawing suggests that it was purchased in 1968. Selle bought the drawings from the Goldowsky Gallery in New York. It is likely that she knew Noah Goldowsky from his days in Chicago when he co-owned a gallery with B.C. (Bud) Holland from whom she had previously purchased works. Richard Bellamy, an art dealer who was often at the center of cutting-edge art production during the 1960s, maintained an office at the Goldowsky Gallery although he largely operated as a private dealer. Selle specifically mentions Bellamy in the record book, also indicating that he was the impetus for her donation of another drawing in the series to the Museum of Modern Art in 1968 (MoMA purchased an additional drawing from the series that same year). Bellamy had a long-term association with Leslie, and was one of the actors in the film “Pull My Daisy.” It is notable that Leslie would have sold these drawings at this time, particularly as they related to a painting series in process. On the other hand, the 1966 fire had destroyed much of Leslie’s new work, and these particular studies might have already served their purpose.

Initially, I thought the work was black ink and wash; however, published sources clearly state that Leslie used watercolor in this series. Leslie had been working in grisaille (a painting technique using only gray pigments to approximate the appearance of sculpture) in his figurative paintings, and was thus highly skilled in working in monochrome. However, attempting to paint landscapes using only black watercolor seems a bold choice. The SCMA drawing is more abstract than either of the sheets in the Museum of Modern Art’s collection, and I wonder about its relation to the other drawings—was it made early or later in the series?

Whatever the specifics, it seems that this drawing was created during a particularly challenging time in Leslie’s life and work. The intimacy and immediacy of drawing may have allowed him to process all that had happened during a tumultuous year.

Carol Selle hung the Leslie alongside other American works in her collection. As it was undoubtedly framed and displayed for the more than fifty years that she owned the drawing, there is some damage from the mat. The dark stain visible around the edges of the drawing is called “mat burn,” and results from prolonged contact with a window mat made from acidic materials. Conservation science and matting materials have dramatically improved since the 1960s when Selle acquired the drawing, and most likely she was not aware that the mat was acidic. Now that the work is in a Museum collection, we can conserve the drawing, restoring the artist’s dramatic use of the white of the paper to represent strong light in the composition.