Frederic Church 200: Celebrating the Connection between Smith College and Artist Frederic Edwin Church

Julia Sumpter ‘27 is a History and Italian Major and Museums Concentrator. She works at the SCMA as a curatorial research assistant to Danielle Carrabino, Curator of Painting and Sculpture.

So, what exactly is Frederic Church 200 and why is the Smith College Museum of Art participating with a label and blog post?

Church 200 is an initiative celebrating the 200th year since artist Frederic Edwin Church was born on May 6, 1826. Many other institutions across the country are participating, such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery of Art, and Church’s estate, the Olana State Historic Site.

Church was the most successful artist in the Hudson River School, a school of New York City-based landscape painters popular in the mid-19th century. In 1891, the SCMA acquired his painting Morning in the Tropics, currently on display on the third floor of the museum. However, the connection runs deeper than one painting: a Smith professor was a key figure in the movement to preserve Church’s estate when it changed hands, and its contents were going to be sold at auction.

In 1844, Frederic Edwin Church first came to the site of his future home in upstate New York with his teacher, Thomas Cole, an artist regarded as the “father” of the Hudson River School. In 1860, still enchanted with the location, Church purchased most of the now 250-acre property. In 1870, he began construction of the main house, drawing inspiration from Persian architecture, which he became familiar with during a trip to the Middle East in 1869. The name of his estate, Olana, may refer to the name of a city in Persia, Olane, meaning “treasure house overlooking a fertile valley.” Church could have come across this name in the book Geographica by the ancient Greek geographer Strabo.

Exterior of the main house at Olana

Photograph by Peter Aaron/OTTO. 2010

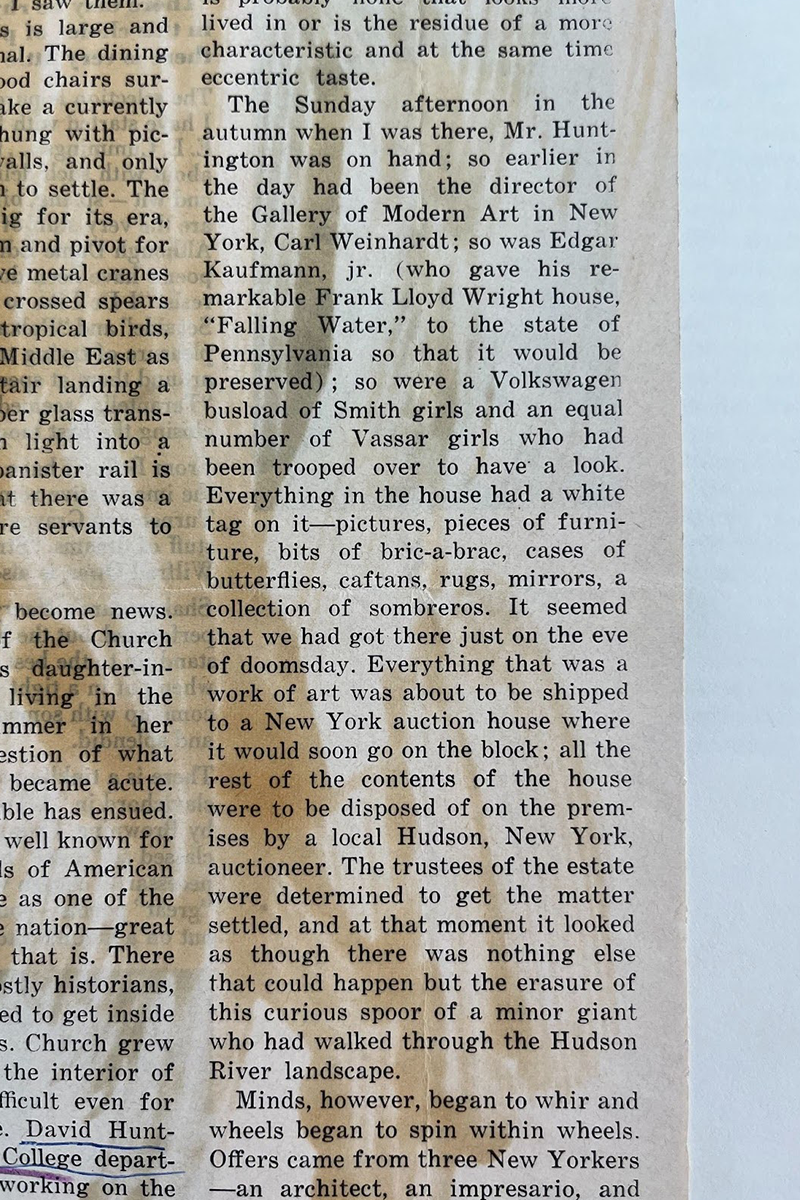

The popularity of the Hudson River School declined after the Civil War, and Church suffered from rheumatism in his hands that affected his ability to paint. For these reasons, Church spent much of his later years working on Olana, which Church scholar Franklin Kelly refers to as his “last great work.” Church was obsessed with Olana; to him, it was the “center of the world.” Given the estate’s importance to such an influential American painter, you can imagine scholars’ horror when Olana was almost destroyed. When Church’s daughter-in-law, Sally Church, died in 1964, the property passed to her nephew, Charles T. Lark. Lark planned to break up and sell the contents of the estate, including 50 of Church’s framed canvases, 600 sketches, hundreds of letters and memorabilia, and his own art collection.

Interior of the main house at Olana

Photograph by Andy Wainwright

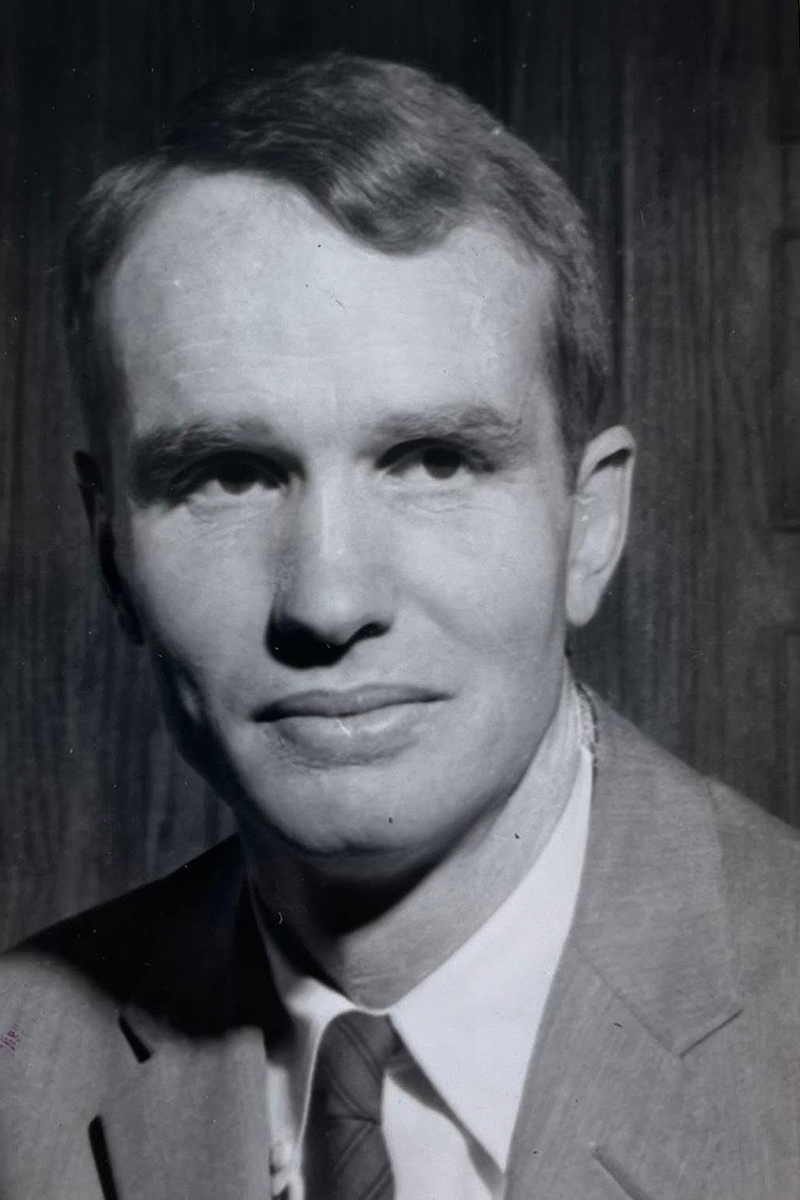

One scholar, David Huntington, was particularly outraged and intervened to prevent the house from being torn down and the estate from being developed. Huntington, a scholar of Church, had visited Olana many times beginning in 1954 as he researched for his Yale dissertation “Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900), Painter of the Adamic New World Myth.” He knew intimately what a unique treasure this house was, virtually unchanged by Church’s relatives since the artist called it home.

Smith professor David Huntington

Fredriks-LaRock Photographers

Smith College Special Collections

Huntington also taught American art history at Smith from 1955-1966, during the movement to save Olana. When the house was being prepared for auction, someone (perhaps Huntington) brought over a “Volkswagen busload of Smith girls… to have a look.” Smithies, can you imagine witnessing this historic moment?

“Persia on the Hudson” by Russell Lynes

Harper’s Bazaar, February 1965

Smith College Special Collections

Huntington immediately leapt into action, convincing Lark to hold off on the liquidation process and give him the chance to raise the $470,000 necessary to purchase the estate. In 1965, Huntington co-founded and became vice president of the Olana Preservation, Inc., an organization that worked to raise money and awareness for Olana. Huntington took on the task of explaining why Olana was worth saving, lecturing around the country, and contacting people for support. In fact, his wife remembered that Huntington had such a high phone bill that the IRS thought he was involved in a gambling ring. The proceeds from his 1966 book The Landscapes of Frederic Edwin Church: Vision of an American Era also went towards the preservation of Olana, and he acted as a consultant to a 1966 exhibition on Church, “Frederic Edwin Church (1826-1900): A Retrospective Exhibition.” This exhibition, organized to garner support for Olana, traveled to Washington, D.C., Albany, and New York City.

The Olana Preservation, Inc. was not able to raise enough funds to purchase the property, but they succeeded in gaining the attention of New York State. The state’s legislature introduced a bill in 1966 to acquire the property, and Governor Nelson Rockefeller signed the bill into law on the steps of Olana, saving this historic estate. The New York State Historic Trust, part of the State Conservation Department, assumed responsibility for Olana and ensured its protection. The successful preservation of Olana has served as an example and an inspiration for the preservation movement and has reignited a popular interest in historic preservation.

Governor Nelson Rockefeller signing the bill to acquire Olana

Courtesy of the Rockefeller Archive Center, Tarrytown, N.Y.

Today, Olana is one of the most intact artist homes in the world, thanks to a Smith professor.

Olana is only about 2 hours from Northampton, so go visit this historic estate!

To learn more, visit:

Faculty and staff biographical files, College Archives, CA-MS-01008, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

The Olana New York State Historic Site website.