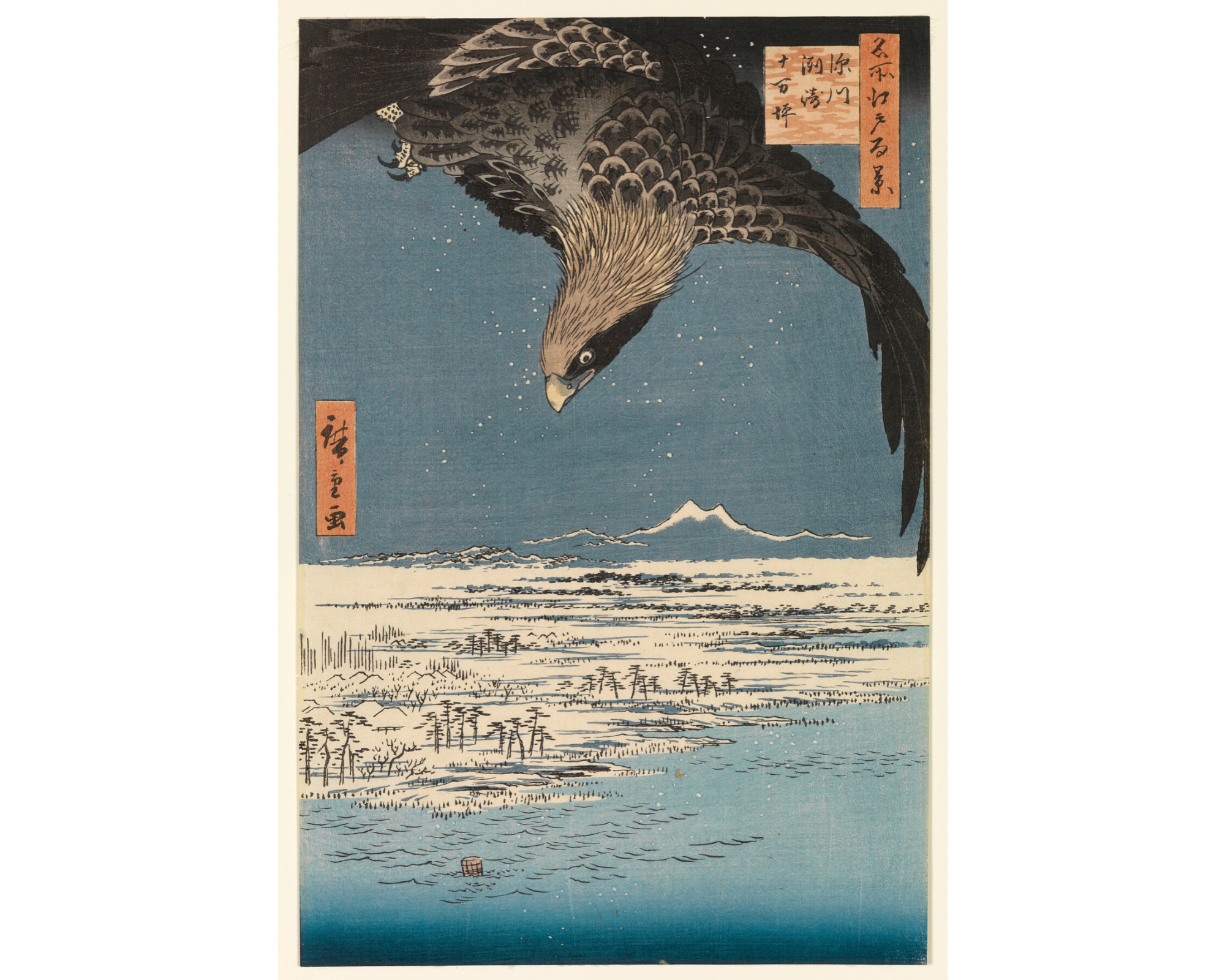

"Fukagawa Susaki Jūmantsubo”: ukiyo-e culture, viewing the city of Edo, and the emergence of commercial art in the time of the Tokugawa Shogunate

Guest blogger Hannah Goeselt is a former Cunningham Study Center student assistant, Art History Major, and a graduate of the Class of 2020.

I first encountered this print as the cover image for the mystery collection “The Curious Casebook of Inspector Hanshichi: Detective Stories of Old Edo” by Kido Okamoto (translated by Ian MacDonald). Serialized from 1917-1937, the stories are told from the perspective of an old detective reminiscing on his adventures in his youth, the individual stand-alone stories taking inspiration from Sherlock Holmes tales of Sir Conan Doyle. As a student worker at the Cunningham Center I stumble across all manners of treasure in the archival boxes, but it was still a surprise to be met with a familiar image while going through a stack of prints.

The swooping wings of the hawk span the top of the print, outlined by the calm blue sky and falling snow. The hawk draws you into the scene with its golden eye, prompting you to follow its gaze across the landscape below. Its body is a striking diagonal swoop over the paper, where the viewer has the unique perspective of being at eye-level with the bird, looking down alongside it at the disorientingly distant snowscape.

Utagawa Hiroshige, otherwise known as Andō Hiroshige (Hiroshige is an official artist’s name passed down from teacher to apprentice), was known as a prominent ukiyo-e artist in the late Edo period (1608-1868). He’s most famous for his series The Fifty-three Stations of the Tokaido (Tokaido is the name of the road linking Edo, the seat of the shogunate, to the imperial city of Kyoto). An ukiyo-e print is a multi-colored wood block print, where each color is divided into a separate block and registered (lined up with the previous image sections of the print) on the paper to gradually build up the final, full color image. These prints were relatively cheap to produce as the process broke down the distribution of labor between artist, carver, and printer, and so became the first fine art in Japan designed to be a mass-market commercial venture.

These prints were immensely popular with the merchant class, depicting scenes from famous plays, favorite celebrity actors and folk myths. Many famous artists of the period worked in ukiyo-e, and among them Hiroshige is considered one of the last great masters of the genre. This is in part due to the advent of the Meiji era (1868-1912), which saw a rapid spread of Westernized culture in Japan a decade after his death in 1858, and a lack of interest in the more traditional styles and iconography that marked ukiyo-e as a form unto its own.

Fukagawa Susaki Jūmantsubo is part of a series of 118 prints made at the end of the artist’s lifetime titled One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, divided into the four seasons. Edo, the old word for Tokyo, became a thriving metropolis in this period due to the rising population of wealthy merchants who were denied the class status of the samurai aristocrats but had enough wealth to lead an aristocratic lifestyle of leisure. Ukiyo-e prints, literally translated as “images of the floating world”, come out of this environment; “floating world” being the term commonly used to refer to the large entertainment industry and rampant material consumerism that flourished under merchant patronage, particularly kabuki theatre and the fashion industry. Originally a Buddhist doctrine on the impermanence of human life, the term was appropriated as shorthand for Edo’s luxury culture, implying one should enjoy what pleasures such a short life has to offer.

The prints served as both art and entertainment. Utagawa Toyokuni III’s 1857 Merchant print triptych from the series The Four Classes of Society is an excellent example of ukiyo-e culture of the time. Here, brilliantly dressed patrons admire a publisher’s stall of colorful prints in a vibrant display of Edo’s thriving publishing business. For the first time, art was affordable to a general populace other than aristocrats: the merchant class could take home images of their favorite actors from the latest show in the kabuki district, hang them on their walls to be admired for a time, and then discard them when they went out of fashion. In this way ukiyo-e prints were a great departure from previous forms of Japanese art, as it was mass produced and ephemeral: an art available to the people, easy to duplicate and distribute widely. It was the embodiment of the impermanent pleasures emblematic of life in the floating world.

The artist Toyokuni III, more famously known as Utagawa Kunisada, was a contemporary of Hiroshige’s, both working in Edo in the field of woodblock printing. Here, beautiful women, a very popular subject in the genre, are dressed in very fashionable kimono patterns and styles. Fashion was a luxury prone to swift obsolescence as tastes in wealthy Edo changed as quickly as they do in the industry today.

The series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo, as well as Kunisada’s Merchant, follow in this vein of fashion; people in the print series all wear intricately patterned dress and bright colors. But unlike Kunisada and other contemporaries, Hiroshige makes sure this all takes a backseat to the landscape itself. Many of the prints in the series, like Fukagawa Susaki Jūmantsubo, have no people at all. The interesting thing about Hiroshige’s series is that, in addition to being a commercialized art form, it intersects visually with a different form of commercialism: the tourist industry.

Hiroshige’s propensity for beautiful natural scenes and local activities in Edo echoes the popular practice of meisho zue, illustrated guides of a city’s famous locations, which worked as tourist booklets of bound woodblock prints for sightseers both visiting and local. One Hundred Famous Views highlights the city’s best qualities in much the same way. As an aside, it is interesting to note that the artist’s son-in-law and successor, Hiroshige II, had a successful series of Edo Meisho Zue after Hiroshige I's death, so such trends were likely on his mind when creating his ukiyo-e series.

Under the period of Tokugawa rule, ukiyo-e evolved into not only an art genre in of itself, but the object of a consumerist publishing business in a time known for its material prosperity. The print style epitomizes the commercialization of urban life in Edo Japan, especially that of its luxury entertainment culture. Ukiyo-e prints are art meant to entertain the viewer, to please the eye, but also served as a form of advertising, showcasing other forms of luxury entertainment, be it scenes from plays, popular folk stories, women in fashionable dress, or beautiful landscape scenery. It was an object of pleasure as well as a promotion of further revelries in the city.

In the late Edo period the print style spanned the breadth of genre from famous historical scenes to intricately dressed courtesans and popular ghost stories. They would serve as posters of current popular actors, site-seeing guides for tourists, and even fashion advertising. Today, we appreciate these fantastic scenes for their rich colors, technical precision and sophisticated artistry. Though meant to be an ephemeral production, the masters of ukiyo-e have left a lasting impression the visual conscious.