Ghosts in the Streets: Whistler and Photography

Amanda Shubert is the 2010-2012 Brown Post-Baccalaureate Curatorial Fellow at SCMA.

My summer corridor show, Image and After-Image: Whistler and Photography, pairs the etchings of James Abbott McNeill Whistler with nineteenth century photographs to look at the relationship between the revival of etching and the birth of photography in the Victorian era. Whistler, a pioneer of the Etching Revival movement that sought to transform etching from a medium for technological reproduction to an art form of spontaneity and refinement, brought a vivid new imagination to the aesthetic possibilities of the graphic line. But unlike etchers, early photographers were dealing with an entirely new technology.

Picturesque street scenes were seen both in etchings and in photographs during the Victorian period. While photographers could document the way city streets actually looked, they were also cramped by an odd limitation. The long exposure times required by early cameras made it impossible to record objects in motion. Photographs of street scenes during this period are usually eerily devoid of people. They might have walked down the street while the picture was being taken, but they don’t appear in the image: they slip outside of the camera’s view and melt out of sight.

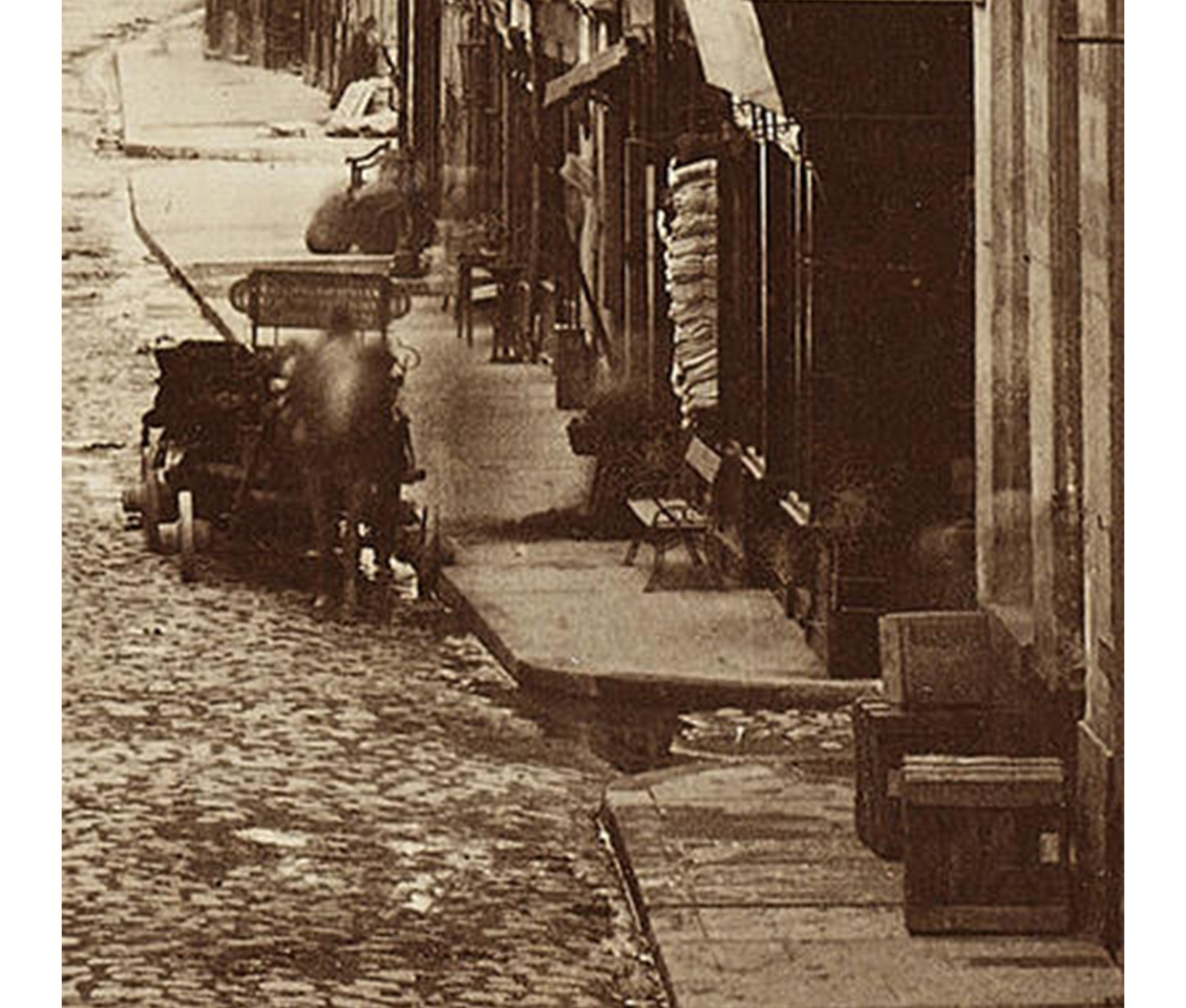

Detail from Departement de l’Aube Archeologique & Pittoresque.

Occasionally, however, moving objects are half-recorded by the camera, creating whitish blurs in the photograph known as “ghosts.” In this photograph by Gustave Lancelot, the ghost of a horse is discernible at the front of the carriage on the right side of the street. (The horse’s front legs are clearly articulated but its torso and head are out of focus.) Two other ghosts that mar the surface of the image—one on the sidewalk beside the horse, beneath the streetlamp, and one on the right-hand sidewalk at the first street corner, between the three square boxes—indicate the presence of people moving through the photograph. By contrast, a single figure, perhaps strategically placed by the photographer, is clearly represented on the left sidewalk, sitting in a chair.

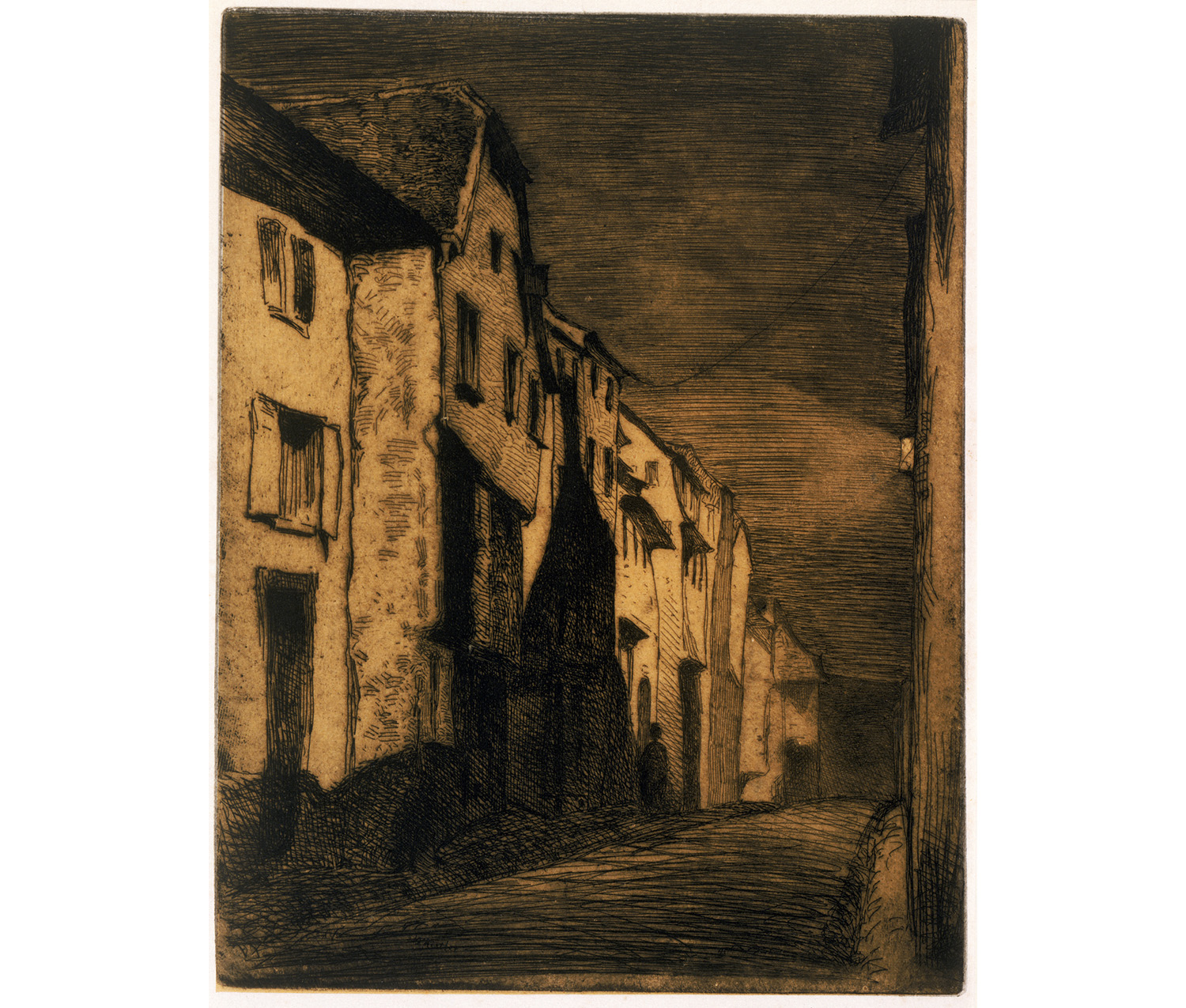

James Abbott McNeill Whistler. American, 1834–1903. Street in Saverne, 1858. Etching printed in black on paper. Gift of Jean MacLachan, class of 1937. SC 1969.30. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe.

Lancelot’s photograph is paired in the exhibition with Whistler’s first ever street scene, called Street in Saverne. Here, Whistler brings a more deliberate ghostliness to his depiction of a city street, using dramatic light and dark contrasts, a tunnel-like composition and apparitional shadows to create an unsettling intensity. The single ghostly figure, like the ghosts in the Lancelot print, seems to be melting into shadow. Whistler’s choice of a nocturnal scene reflects a singular change in urban planning in the mid-nineteenth century: the introduction of street lamps to European cities. Street lamps transformed nocturnal views, both in terms of the lived experience of cities at night and the possibilities for artistic representation. By reinforcing the mystery of the street seen by lamplight, both ominous and beautiful, Whistler depicts the ghostly uncertainty of his increasingly modern, industrial world.