Younes Rahmoun. Moroccan, b. 1975

7-minute video animation

SC 2018.32 Purchased with the Carol Ramsay Chandler Fund

Grounded: Experiencing the Work of Younes Rahmoun at Smith and Abroad

Indigo Casais ’23 is an art history and English double major. Indigo is also the 2022-23 Kennedy Museum Research Fellow in Art History at SCMA, working with Emma Chubb, Charlotte Feng Ford ’83 Curator of Contemporary Art.

When I first arrived at Smith in September of 2019, one of the first works of art I saw at SCMA was Younes Rahmoun’s video Habba (Seed). [1] The piece is a seven-minute animation illustrating the life cycle of a seed, which eventually blooms into a tree and grows fruit before its seeds are blown away to (presumably) start the cycle anew. With its minimal color palette and ambient music, Habba renders the seed an object of meditation. Because of its emphasis on close looking and thoughtful consideration, Habba confused me at first. I didn’t understand why a seed was so important to Rahmoun or what I was supposed to take away from the work.

Collection of The Botanic Garden of Smith College.

Luckily, I was able to learn more about Rahmoun’s work when he came to campus during my first semester for the conference “Light, Brick, Jute, Earth: Younes Rahmoun,” organized by my supervisor, curator Emma Chubb. While Rahmoun was at Smith, he planted a tupelo tree by Paradise Pond as part of the performance Chajara-Tupelo (Tree-Tupelo). [2] The performance, conducted entirely in silence, brought members of the Smith community together with visitors from around the world to watch as Rahmoun planted the small tree and watered it for the first time. After the performance, I began regularly visiting the tupelo tree. I always stopped to take a picture of it as it got taller, as its leaves changed, fell, and grew back over the seasons.

I didn’t know why I was so drawn to the tree. I still don’t totally understand it, but I think it has something to do with the meditative quality of returning to one spot again and again. The tree is always there. It’s a constant. But at the same time, it is different every time I see it. I also love the way the tree carries memories of interactions between humans and nature, especially the memory of all the people who came together to witness its planting. Rahmoun affirms that one of his key interests is different types of connection, stating in an interview that his work seeks to answer questions “about the relationship between me and the cosmos, me and other people, me and nature.” [3] Though Chajara-Tupelo may seem to be all alone on the edge of the pond, it is reminiscent of a moment of interconnection and togetherness.

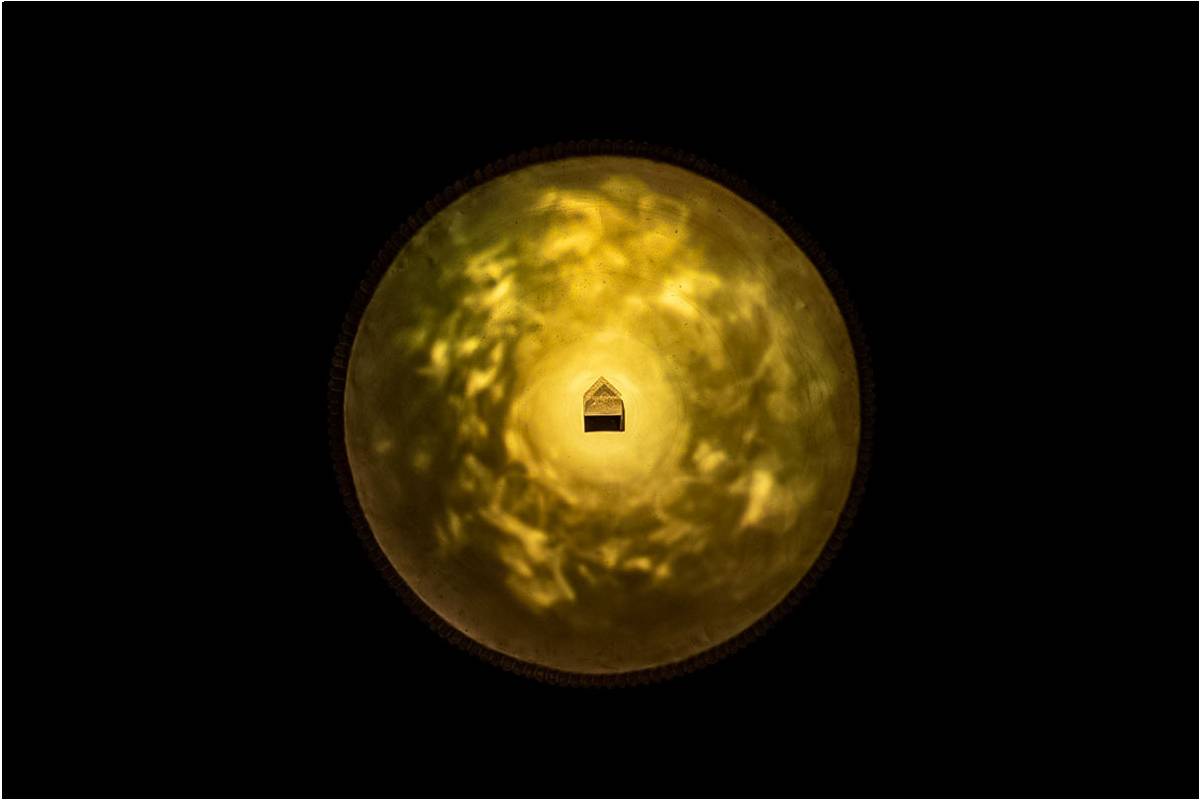

Last year, when I traveled to Paris to spend my junior year abroad, I was grateful for regular opportunities to see Rahmoun’s work. His gallery, Galerie Imane Farès, was just a ten-minute walk from my apartment in the sixth arrondissement. From February to June of 2022, Rahmoun had a solo exhibition entitled Madad on view at Imane Farès. I visited often, always taking the stairs down to the lower-level gallery to see Nor-Manzil-Nor (Light-House-Light), my favorite piece in the show. The work is a wall projection that mimics the circular form of Habba, but focuses on the theme of the house as a unit symbolizing human connection.

Over the past three years, I’ve learned that what Rahmoun’s work is really about is this sense of connection. Videos like Habba are about how elements of the universe, like a seed or a house or a tree, hold memories of so many different instances of togetherness. When I had just arrived in Paris and was far away from everyone I knew and loved, I went to see a work by Rahmoun, and I felt a little less alone. Now that I am back at Smith, walking by Chajara-Tupelo on a cold fall day brings me back to my time abroad, to all of the art I saw and the people I met there. The work keeps me grounded. I see it and I pause for a second, approaching it to see how it has changed. Then I walk away, trusting it will still be there when I return.

[1] Habba is available to watch on Rahmoun’s website.

[2] You can view Chajara-Tupelo and other artworks across campus using the map Beyond the

Museum: Art on Smith’s Campus.

[3] Younes Rahmoun, “When 77 hats do the lotus position: the cosmic world of Younes

Rahmoun,” interview by Homa Khaleeli, The Guardian, June 26, 2018,

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/jun/26/when-77-hats-do-th…-

cosmic-world-of-younes-rahmoun-jameel-prize.