From Home: An Interview with Lucy Xiaochuan Liu '21

Sophie Poux is a student assistant at the Cunningham Center, a Government major, and a member of the class of 2021. From Home is a series of interviews she is conducting remotely this fall.

Lucy Xiaochuan Liu is a member of the class of 2021 and a major in both Studio Art and French. She is the author of the chapbook, The Rye of Pondering, selected by poet Cameron Awkward-Rich and published by the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and Of the Grassland with No Boundaries which No Fire Can Burn Down, recipient of the bronze PX3 Prix de la Photographie Paris. Lucy received a 2019 Tryon Prize from the Smith College Museum of Art for her installation “Boat,” and her work has been recognized by the Los Angeles Center of Photography, the Smithsonian Institution’s Folklife Magazine, Paris Lit Up Magazine, and Columbia Journal. She is a recipient of the Pollock-Krasner Foundation Fellowship to complete an artist residency at the Woodstock Byrdcliffe Guild which has been deferred to 2021.

At the end of September, Lucy and I sat down over Zoom to talk about learning remotely, the art world in China, and making work about grief. Lucy and I got to know each other last year while we were abroad in Paris, and I enjoyed hearing about what she’s been working on since we left France in March.

Lucy, what does a typical day look like for you right now?

I’m living with my parents in Beijing and there’s a twelve hour time difference from Northampton. I get up at noon and I’ll do homework and my artwork – sometimes I’m productive and sometimes I’m not – before my classes start at 9 or 10 in the evening. My senior studio class is held from 1:40 am to 4:40 am! I also have a part time job with Photo World Magazine. I do an interview with an artist for each monthly issue so in my free time I work on that.

I know I’m spoiled. It’s very easy to be in Beijing right now. Life is almost back to normal: people can go out with masks. There’s sometimes news in other provinces about cases popping up but my dad, as a doctor, is not seeing any coronavirus patients which I am really glad about.

Have you been going to museums since you’ve been home in Beijing? I know that you were spending a lot of time at museums in Paris.

I’ve definitely been missing the museums in Paris. I’ve been to museums here once or twice a month, though. There’s not very much to see because everything has just reopened and restarted. There are great artworks and artists but the opportunities to see them are rare and what museums do – the curation and how they structure the activities surrounding the exhibition – just isn’t like Paris. There also isn’t the audience that there is in Paris, you know? Any ordinary lady will go to the Palais de Tokyo (the Parisian museum of contemporary art). My first host grandmother did: she’s in her late seventies and likes to see all of that stuff, although she doesn’t really appreciate all of it. But I don’t think the audience in Beijing is that avid about art, and art is still pretty exclusive. In the US, too! I’m taking the Modern, Postmodern, Contemporary art history class with Frazer Ward this semester and we’ve been talking about how it’s twenty-five dollars to go to the MoMA! In Paris, you get to see art for much less.

Lucy Xiaochuan Liu, b. 1999. Self portrait from 'Of the Grassland with No Boundaries which No Fire Can Burn Down.' 2020.

Tell me more about the art world in China.

The Chinese market, the ecology, isn’t fully developed yet. In China, the art market opened up to an international audience in the late nineties. For the first time, Chinese artists had the opportunity to work with international collectors, to learn about and participate in world-class exhibitions. Unless they had studied abroad before (like Ai Weiwei or Wu Hung) which was very rare, it was also many artists’ first opportunity to learn global art history in a systematic manner. Although there are excellent Chinese artists and art professionals, the industry today is generally still lacking people who are trained, who really understand art and know what they’re doing. The people running many of the art institutions don’t have a background in art.

In China, the general expectations of people’s level of art education is low. A lot of art students at Smith do many internships and build professional connections at a really early stage of their studies. But it’s really hard to find a good internship in art in Beijing. In the US you have all of these big museums and institutions where you can work as an intern, and even galleries which aren’t as well known are very structured and there’s a lot to learn. But in Beijing, that isn’t really the case.

When did you decide you wanted to be an artist?

When I was five, I declared that I wanted to be an artist. At the time, I thought all artists were painters. I drew a lot but my eyesight got really bad and I needed to wear glasses. My parents were afraid that my eyesight would get worse if I drew all the time and so they forbid me to draw. I did a little bit of music but I’m not incredibly talented. I did theater, too, and liked that.

Even today, my parents don’t really know what to do with me. My parents and my family are not really artistic and art kids, at least in China, have to train specifically in drawing from a young age and their parents are super cultivated. They’re typically college professors or something like that.

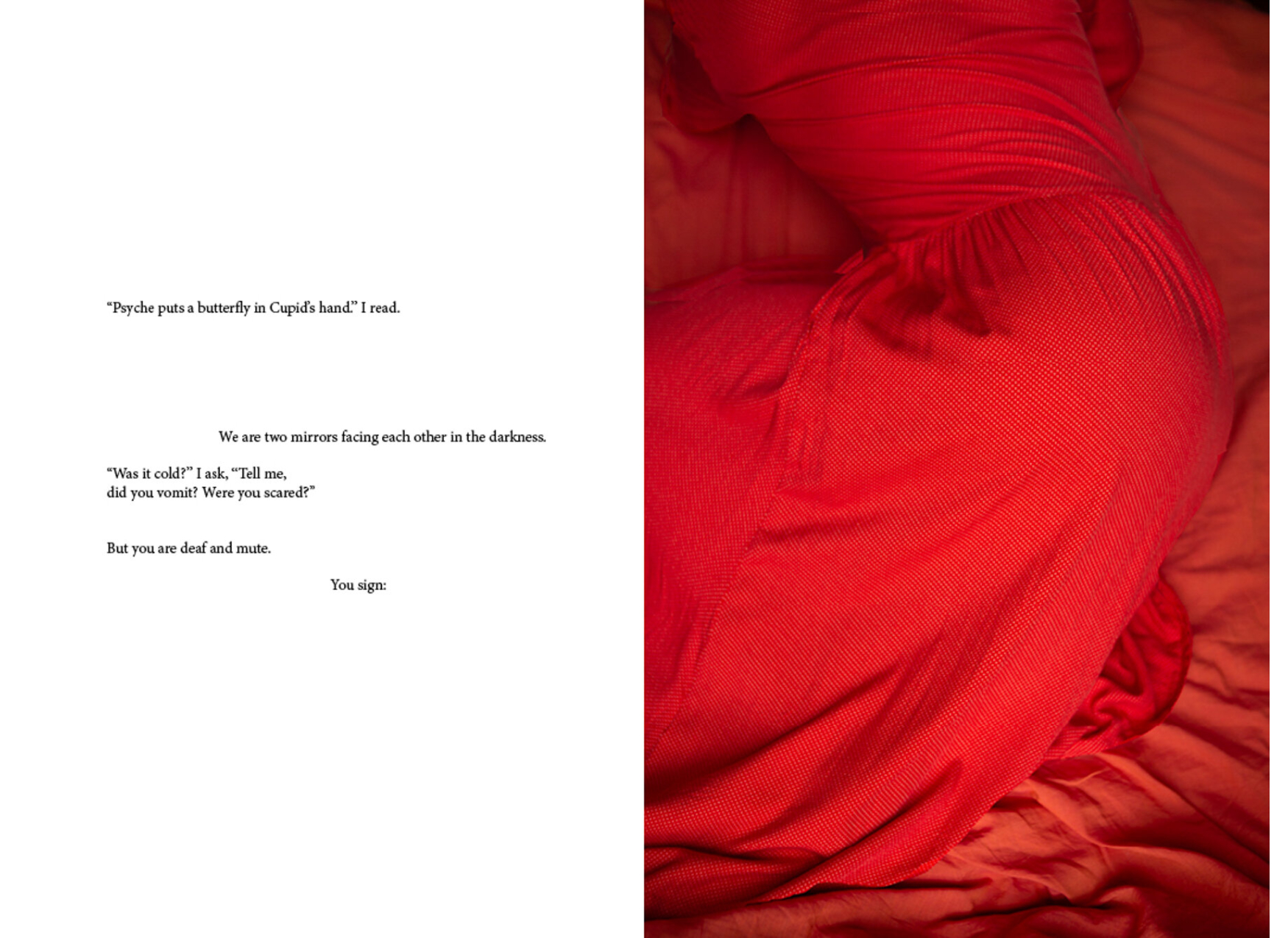

Lucy Xiaochuan Liu, b. 1999. Self portrait and poem excerpt from 'Of the Grassland with No Boundaries which No Fire Can Burn Down.' 2020.

Did you plan to study art at Smith?

Before going to Smith, I thought I would do something related to art and literature but I had always been told I couldn’t be on the creative side of those things. I was interested in reading and enjoyed visiting museums, though, and that has been a good base for making art and writing poetry now. At the time, there weren’t very many shows to see in Beijing – or maybe there were and I just didn’t know about them because my family didn’t visit museums – but I always went to the National Museum. Even though the National Museum is very, very traditional, I remember a huge exhibit of Polish painters from the Middle Ages to present. There was also a Rodin show which included Rodin sculptures from all over the world. That was all really great.

When I was in high school, I sat in on classes at Peking University. They don’t have an art history major but they had a really amazing art history professor. He grew up during the cultural revolution. Because he worked as an apprentice for a traditional artist, he had training in studio art. He personally went through some turmoil during the cultural revolution. Later, he went to college and focused on art history and then studied abroad in Germany. I really appreciated his perspective on things both traditionally Chinese and Western. I was very impressed! That was my first impression of art history and so I thought that that was what I wanted to study.

And then I got to Smith and I just stumbled upon a whole new world! I started taking many art and poetry classes, and I decided that studio art fit me best.

What is it like to both write poetry and make visual art?

I think in a mixture of images and words, so it’s challenging to figure out how to present my thoughts and which parts to translate into which form. A professional photographer who I really respect once told me that I’m not acknowledging the shortcomings of the photographic medium: I should first acknowledge that there are things I cannot do in photography and then I will be able to try and use the medium to its fullest. I started wondering if, in my photography and poetry, the poetry is something extra or if it is trying to create an easy way out for a problem in photography such as my technical shortcomings. I’m constantly doubting myself in that respect. I’m trying some safe endeavors and I hope that maybe, step by step, I can try and create something with the strong points of photography, installation, and words.

Some of these attempts have been writing poems about art. I have a whole series of poems about black and white artworks. I think when you don’t have color, you start to notice other things like texture, or sensory elements. You use that more when you see a color image. By being denied one path and trying to find another, the process results in hope. So this whole series of poems were about hope.

Lucy Xiaochuan Liu, b. 1999. Self portraits from 'Of the Grassland with No Boundaries which No Fire Can Burn Down.' 2020.

Tell me about your creative process.

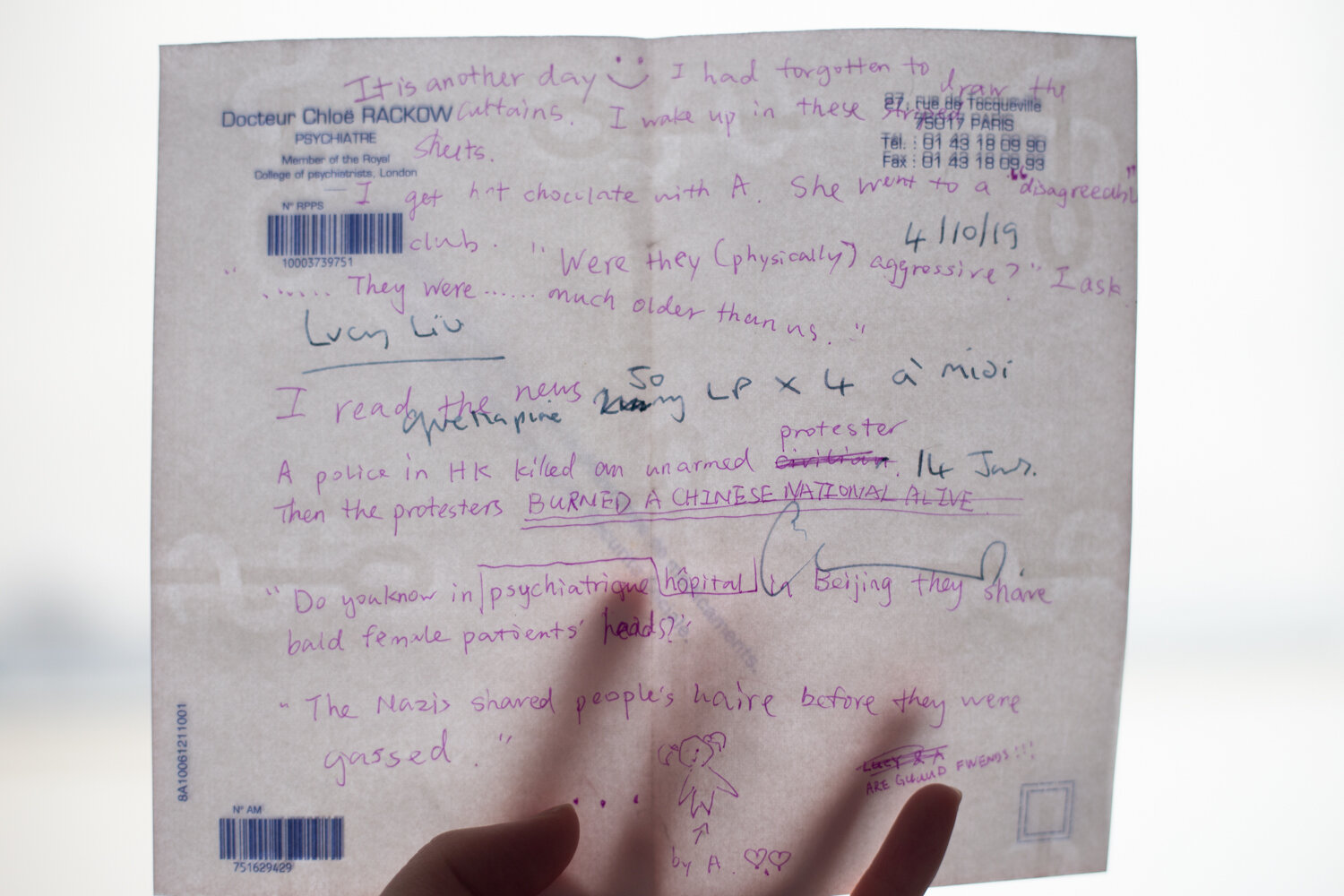

It never works when I try to sit down at my computer and write a poem. I carry a notebook around with me and scribble things that I see because if I don’t record them, I forget. When I don’t have a notebook with me I’ll use my phone. And when I have collected enough of these things I type them out on my computer and try to find connections between them. That’s the most ideal practice but it doesn’t always happen that way.

When I really, really can’t think of anything to write I sometimes take a book that I like and circle random words that I see or am interested in and I try to make new connections between them. I always feel like this process ends up corresponding with my instincts. With poetry, I never know how it’s going to end up but it always reflects something in myself that I might not have noticed before.

With my art practice, I do a lot of self portraits. Taking self portraits can be a prompt in itself when I don’t know what else to do. I recently have been trying to try out different locations, different formats, different ways of printing on paper, on fabric.

And I collect a lot of things and I hope that one day I’ll use them. For example, just right here on my desk here, there is this really ugly fruit. I think it’s rotting! I found it on the farm where my grandparents used to work and, you see this little rubber snake? I don’t know why I put this fruit on the snake.

How do you know when your work is finished?

I think my chapbook is finished. Sometimes when I read a poem I wrote three months ago, I think it is ridiculous and terrible and I tear it up. But I wrote my chapbook a year and a half ago and I still like it even though I know I would never write something like it again. It feels precious because it documents what I was thinking at that moment in my life, so I’m really glad it’s such a nicely curated, small series and I don’t want to do anything to it. And I’m also glad it’s all published so that it can never again be distributed. But, for other poems, I don’t think they can ever be finished. I keep going back and changing them and thinking that they’re terrible. It’s similar with my artwork as well.

What are you working on right now?

I sometimes use imagery from poetry as inspiration for my visual art. Right now, I’m creating a modern parody of the myth of Orpheus. My interest in the myth began in Paris. I took a class at the Sorbonne all about Orphism – orphisme – and how European poets in the surrealist movement wrote about the myth of Orpheus. There is just so much about that myth I found interesting: his journey through hell and the iconic moment of him looking back on Euridices and causing her loss, and how he returned to the world of the living and, well, how he died. For my honors thesis I’m doing a photography series with installation, creating my own parody of that myth.

Lucy Xiaochuan Liu, b. 1999. Self portrait from 'Of the Grassland with No Boundaries which No Fire Can Burn Down.' 2020.

Much of your work, including The Rye of Pondering, your chapbook, is expressions of grief. What is it like to make work about grief?

People always ask the question, what is the meaning of life? I’m not just bringing this up because it’s a horrible question. I mean, how do you really calculate the value of grief and suffering? The question of the meaning of life, or the meaning of this work, is a tricky question. I think that sometimes the value of grief and suffering are that they capture a moment, and, by capturing it, create a sense of existence.

But sometimes, the reader or viewer of a piece turns away from it because they can’t stand the grief, because the piece imposes too much on them. When that’s the case, what’s the point? I think it’s important to find another model for the subject; rather than demonstrating a specific process of how a person was mangled, talking about it more broadly. I try to use my art to aim at something, a larger existence than my own experience. I think there’s more receptivity and room for interpretation in that.