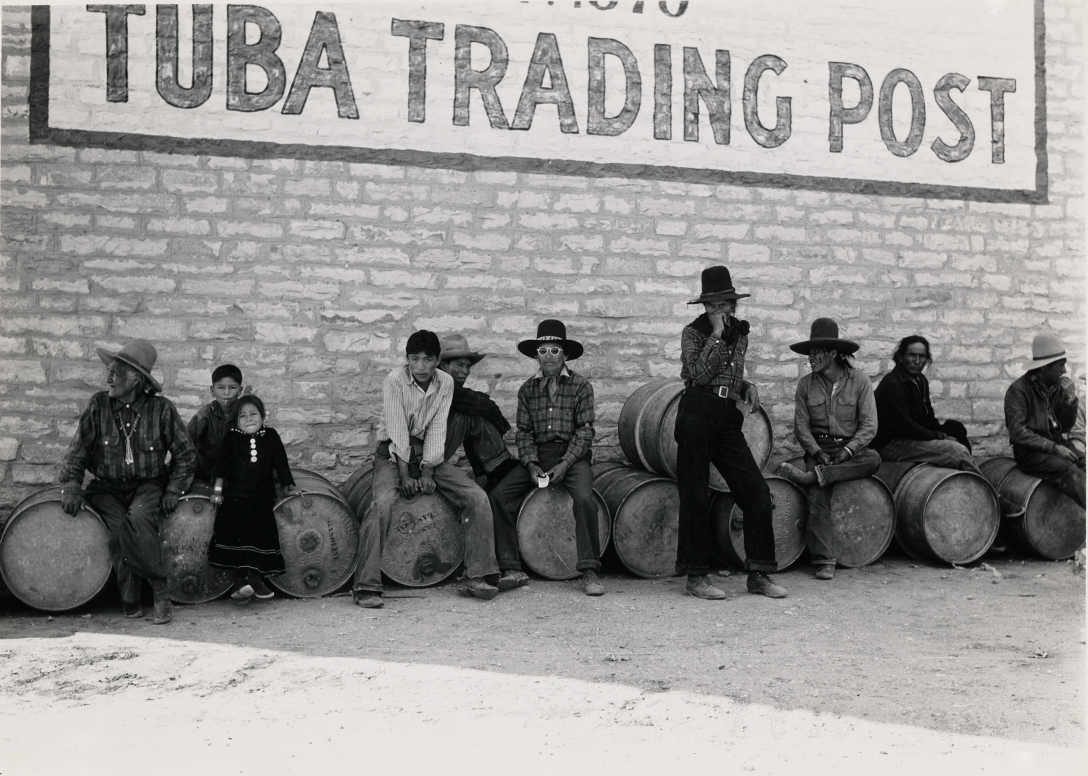

ca. 1936-37, SC 2021.28.3,

|

How Peter Sekaer's Daughter Kept His Legacy Alive

Sophie Poux conducted an interview with Chris Sekaer, daughter of the photographer Peter Sekaer (1901- 1950) regarding her fathers legacy. Sophie was a student assistant in the Cunningham Study Center during the 2018-2019 and 2020-2021 academic years. She graduated from Smith with a BA in Government in May 2021.

SCMA recently received a generous gift of 26 photographs by the Danish American photographer Peter Sekaer. Peter Ingemann Sekaer was born in Copenhagen, Denmark in 1901. At the young age of seventeen, he left Denmark for New York to escape an overbearing father and his family’s expectations to build a career in their machinery import business. He made his way west throughout his late teens working odd jobs as a rancher for his uncles in Canada, as a lumberjack, and as a forest firefighter. He returned to New York in 1920 and by 1922 had a thriving business — Ingemann Designs — painting and screen printing signs, movie posters, window exhibitions, and theater programs and sets. He enrolled in painting classes at the Art Students League in 1929, studying with teachers such as Jan Matulka, Vaclav Vytlacil, Hans Hofmann, and George Grosz. Sekaer also met fellow student Ben Shahn who introduced him to Walker Evans, both of whom would go on to work as photographers for the United States Government Resettlement and Farm Security Administrations producing one of the most iconic bodies of photography of the 20th century.

It was not long before Sekaer shifted his focus from painting to photography. By 1933, he was working as a commercial photographer and the following year he left the Art Students League to study photography with Berenice Abbott at the New School for Social Research. In 1935, he began to assist Walker Evans who was soon hired as a photographer by the RA. Sekaer accompanied Evans on a work trip through the South that winter. They covered four thousand miles of ground and visited at least twenty-nine cities in a mere two months (Kemmerer, American Pictures).

Untitled [Rural Electrification Administration pole raising in field], Peter Sekaer, American, ca. 1936-37, SC 2021.28.1

In July of 1936, Sekaer was hired as a principal photographer for the Rural Electrification Administration (REA). In 1930, three quarters of rural Americans did not have indoor plumbing and ninety percent did not have electricity. REA photographers’ images were used for internal government memorandums and publications to justify the use of taxpayers’ dollars to provide farmers with low-interest loans to install power lines. As an REA photographer, Sekaer also photographed slums to promote subsidized housing for the US Housing Administration as well as indigenous Navajo and Pueblo communities for the Office of Indian Affairs. He was promoted to head of the REA graphic unit in 1941, a role in which he coordinated photography exhibitions of the work of government agencies’ including the USHA and the FSA. He went on to work for the Office of War Information and the American Red Cross, and in 1945, started his own documentary photography business. In 1947, Sekaer left Washington to return with his young family to New York. Like many photographers working for US government agencies, a reduced demand for documentary photography led to a career transition into commercial photography. In the final years of his life, Sekaer worked for companies including Bell Telephone and Kodak, and was published in magazines such as Glamour, Vogue, and Ladies’ Home Journal. Sekaer died of a heart attack in 1950 at the age of forty-nine. [1, 2]

“A Dust Bowl of Dog Soup: Picturing the Great Depression,” on view at SCMA from November 2019 through May 2020, included the work of three iconic American photographers employed by the Farm Security Administration (FSA) who like Sekaer worked under Roosevelt’s New Deal in the late 1930s and early 1940s: Arthur Rothstein, Dorothea Lange, and Marion Post Wolcott.

I was lucky enough to assist Henriette Kets de Vries, curator of “A Dust Bowl of Dog Soup,” and Manager of the Cunningham Study Center for Prints, Drawings and Photographs and Assistant Curator of works on paper at SCMA, with her preparatory curatorial research for the show.

Chris Sekaer, the photographer's daughter and resident of Leeds, Massachusetts visited “A Dust Bowl of Dog Soup”shortly before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. Chris Sekaer has collaborated with gallerists and art historians to tell her father’s story and make his work more widely available to the public. Seeing the work of a handful of her father’s contemporaries on view at SCMA, she inquired about gifting some of Peter Sekaer’s photographs to the Museum.

Last spring, Chris generously invited me to her home in Leeds for a conversation about her father’s life and work. We sipped coffee, snacked on pastries, and chatted for nearly two hours to the sound of the rushing Mill River. The following interview has been edited for clarity and length.

The work of photographers working for US Government agencies in the late 1930s and early 1940s experienced a resurgence in popularity as it began to receive attention as art — not just craft — in the 1970s and 1980s. What prompted you to share your father Peter Sekaer’s work with the world?

In 1980, when I was 35, I said to mother: “Maybe we should have a show of my father’s work.” I was in a stage of beginning to wonder who my father was because he died when I was quite young. Because the photos belonged to the government, my mother did not believe we could exhibit them.

And then I found a catalogue — I was at Columbia’s Teachers College waiting in line when I saw a catalogue of Walker Evans’ photographs for sale. They all had “FSA” [Farm Security Administration] stamped on the back of them. My mother was able to get in touch with the Krakow Witkin Gallery, and the gallery put a large number of my father’s works in a show a month later. My father was, like, half the show!

I think what I wanted to know most of all was who my father was and if I would have liked him, and if he liked me. When we got the photos out, my mother was very open and willing to look at them. But we were living with my stepfather who was also in the arts, and so I felt like I had to have the impetus to share my father’s work.

What was it like attending that first show at the Witkin Gallery?

I went into the show and one of the gallerists came over to me and said “I have to ask you something. Berenice Abbott is in the other room and says that we have misattributed one of her photos to Peter Sekaer. It says that it was by her in our catalogue.” But the catalogue was wrong. It had misattributed the photo to Abbott, my father’s teacher, and she wanted to be sure. I told the gallerist, “I’m sure. We have lots of prints of this photograph and I’m sure it’s his.”

So I got to meet Berenice Abbott for like one minute. I also met Russell Lee for one minute. I said something like, “oh, you knew my father.” I was at an age where I had no idea what to ask. Finding out who these people were — it was all a part of my interest in my father.

What has it been like to be the main ambassador of your father’s work?

The first time I ever showed anyone my father’s work I took a whole bunch of his photos, probably in a paper bag, to the International Center for Photography (ICP) which at that time was on the Upper East Side. I spoke to a woman there who was very excited about the photos, but she told me that it takes years to arrange a show. I got her feedback and even though I didn’t do anything with it, I did think, oh, these people really are interested. And it’s like you said — it was the 70s and 80s when these photographers really started to become a thing.

I’ve gotten to meet all these people in this world of photography that I would not otherwise have had any contact with. We donated a bunch of my father’s photographs to the Library of Congress. I went down to Washington, D.C. where they have big boxes of the negatives of his work for the REA. His other negatives — for the Housing Authority and the Indian Bureau — were nowhere to be found. They were probably thrown out, as far as we know they don’t exist anymore.

But there have also been [independent] discoveries of my father’s work. Michael Sundell contacted us while he was working on a piece that he wrote on US Government agency photographers for the magazine Prospects in the late 80s. At that time, a warehouse of WPA projects and writings had just been discovered and unsealed for the first time.

There was an album of 20 yellowed pages of contact prints that someone found in their relative’s attic when they passed away. It was published by Steidl, a top press in Germany. It is a beautiful book published by a fantastic press. I really felt like I was along for the ride!

Some people who have inherited art or photography collections find it wonderful and some find it a burden. I’ve always found it a wonderful adventure.

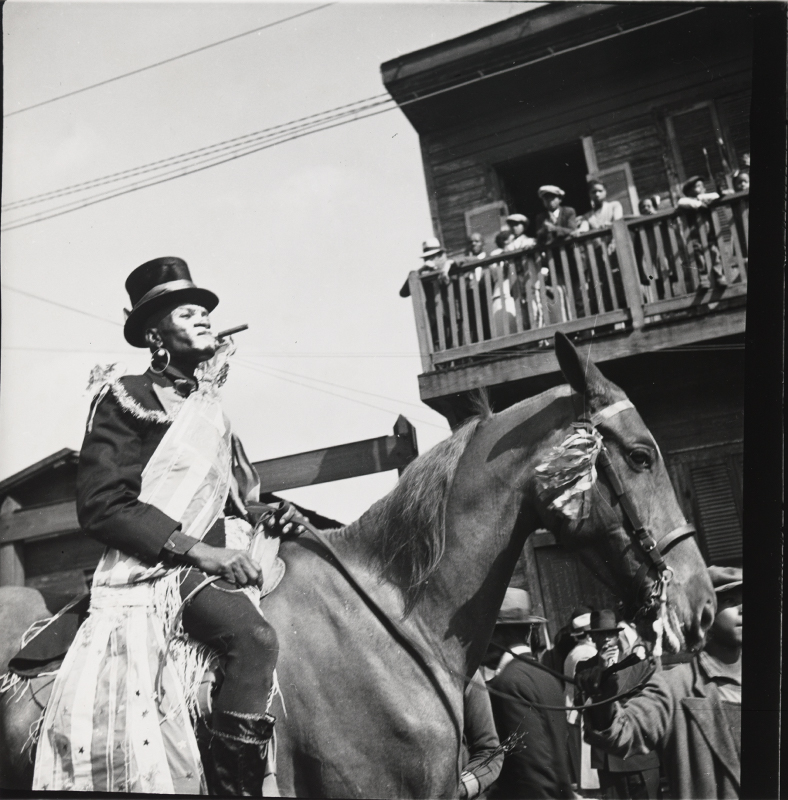

Untitled [man on horse], Mardi Gras, New Orleans, Peter Sekaer, American, ca. 1936-38, SC 2021.28.16

What have you learned about your father through his work?

I myself have very few direct memories of my father because I was five years old when he died. In my journey to find out who he was, I have found his sense of humor and his passion.

A few years ago, I met a guy in a museum in New Orleans who took me on a tour of the French Quarter where the buildings that my father photographed are. These buildings are still there because it’s a historic district. I took some of the same photographs that he did but in color. I don’t think that mine look very good.

What do you hope others will take away from your father’s work as it continues to take on a life of its own?

An interest in documenting people’s lives. My mother always loved the Romans, and what she was really interested in was how they lived their everyday life. I think my father used photography to show the dignity of people who were struggling. My mother said that he photographed people because he wanted to help them. You can see that they were in poverty, that they were struggling, and you might want to help them as opposed to not thinking about them. So, I suppose the underlying humanity of everybody.

Untitled [Goldberg sign at store entrance], Peter Sekaer, American, ca. 1937 (printed 1981), SC 2021.28.26

[1] Sekaer, Christina. Personal Interview. Leeds, MA. 28 April 2021.

[2] Kemmerer, Allison N. Peter Sekaer: American Pictures. The Addison Gallery of American Art and Howard Greenberg Galleries, 1999, pp. 7-17.