The Iconography of Constance Pott

Guest blogger Nicole Viglini is the International Fine Print Dealer’s Association Intern at the Smith College Museum of Art.

This piece discusses works from the The Gladys Engel Lang and Kurt Lang Collection, a collection of prints which was recently donated to the Museum.

In 1902, a London medical school’s newspaper blithely predicted that “Miss Constance Pott will be remembered by her renowned picture of the front quadrangle of the Hospital, issued through the Gazette in 1896.” Later issues of this paper continued to allude to the popularity of her prints. Ironically, Constance Pott (English, 1862 – 1957), a preeminent artist in the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries known for her skillful etchings and her professional partnership with Sir Frank Short, is not remembered for this, or for any other works she produced. Gladys Engel Lang and Kurt Lang attribute the waning appreciation of women printmakers of the Etching Revival, a movement that began in mid-nineteenth-century France, to both external and internal factors, including circumstances beyond their control, individual choices, and the types of relationships the artist cultivated. In the case of Constance Pott, the Langs connect her faded legacy to her death at a time when etching was no longer a popular artistic medium, and to the fact that she outlived most of her contemporaries and many of her students. Pott never married, and had no children to cultivate her legacy. She left her artwork and books to two sisters, and the bulk of her money to one of her students at the Royal College of Art (RCA), Johannes Matthias Daum. Furthermore, Pott did not keep a catalogue of her work. The Langs ascribe her “reluctance for self-promotion” to her Victorian upbringing, underscoring her upper middle class background. They describe a book written by her mother, Mrs. Henry Pott, which was entitled Quite the Gentleman and extolled the virtues of Victorian gender roles. Pott was later remembered by one artist, who had not studied under her, “as an ‘old maid; very, very Victorian, very much respectable.’ She engaged very much in ‘good works.’”

Pott received her training at the world-renowned Royal College of Art. During the mid-nineteenth century as the industrial sector began to rise, various companies sought artisans to take on jobs in crafts, spurring the advent of training schools for industrial design. The RCA was one of these schools, but from the beginning, many of the students attended to learn fine art rather than draftsmanship and other crafts. As the Langs note, Pott, while studying at the RCA in the late nineteenth century, “had not taken to the ordinary daily round of drawing and design, such as adapting ‘a lily or rose to wall-paper, tile, or carpet design.’” She discovered an engraving class and began to focus on creating art. Pott’s long association with the artist Sir Frank Short began in 1891, when Short taught the engraving class at the RCA.

Constance Mary Pott. English, 1862–1957. On the Medway, n.d. Etching printed in black on heavyweight, moderately textured, beige paper. The Gladys Engel Lang and Kurt Lang Collection. SC 2016.62.51.

Pott’s work belies her Victorian upbringing. There is something post-apocalyptic about On the Medway, with its dilapidated pier and skeletal ship masts. The cluster of hovering seagulls begs the question, where lies the carrion? While evidence of human activity is central to the piece, most eerily portrayed by the abandoned, floating barrel, the absence of people contributes to its somber tone, accentuated by a bold use of black. The structure at the end of the pier registers as a haunting relic of a lost civilization. Perhaps Pott found inspiration in the wreckage brought about by the severe economic depression that settled over Europe in the 1890s. A commentary on boom and bust economic cycles, the nature of commerce and humanity’s mark on the natural landscape was hardly subject matter fit for “an ‘old maid; very, very Victorian, very much respectable.’”

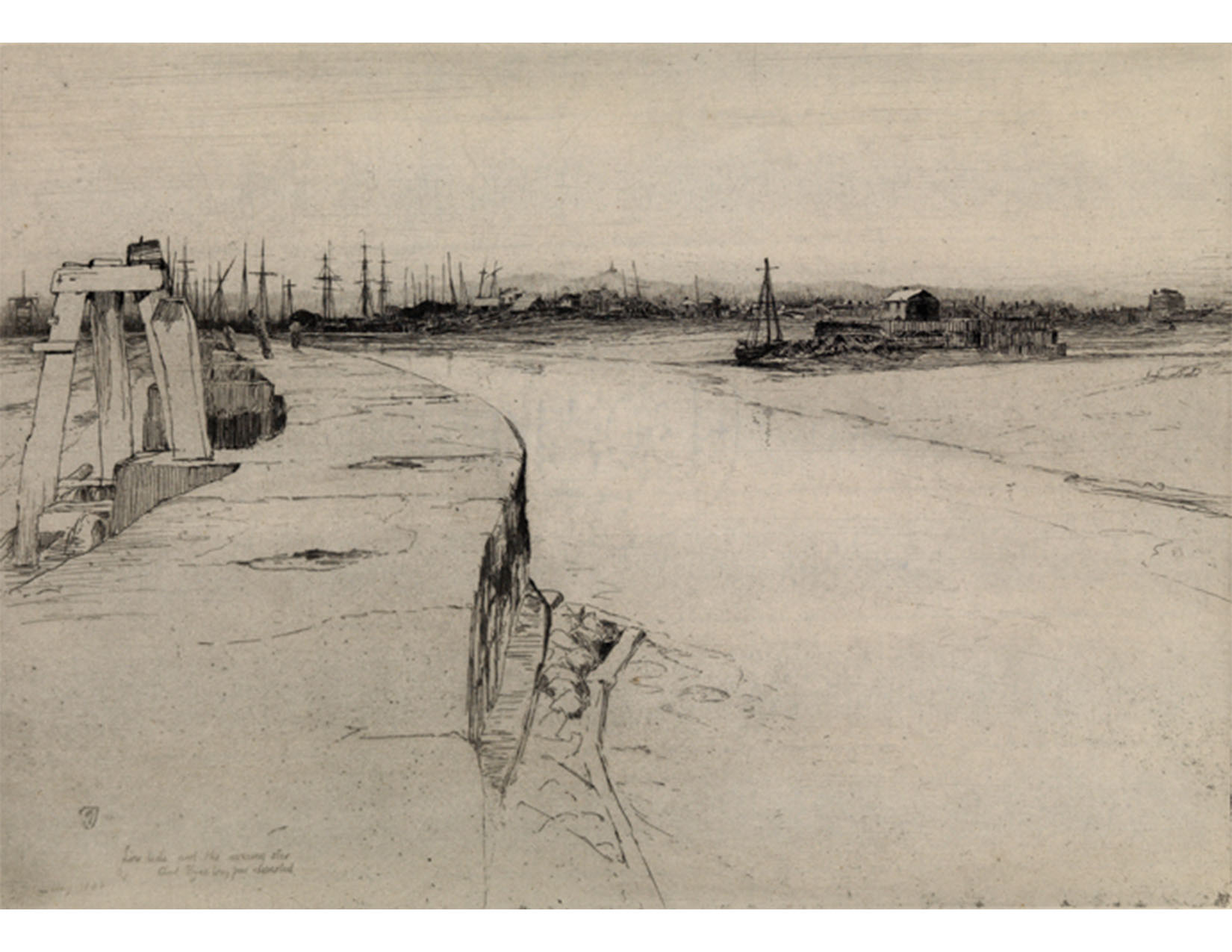

Sir Frank Short. English, 1857–1945. Low Tide and the Evening Star and Rye’s Long Pier Deserted, 1888. Etching printed in black on medium weight, slightly textured, cream-colored paper. The Gladys Engel Lang and Kurt Lang Collection. SC 2016.62.105.

Pott’s connection with Frank Short can be succinctly emphasized by comparing On the Medway with Short’s work, Low Tide and the Evening Star and Rye’s Long Pier Deserted. Short’s piece evokes the same sort of post-apocalyptic feeling. The subject matter and composition is strikingly similar, though while Pott’s use of line is more bold and assertive, Short’s rendition uses more fine lines and appears starker. This difference is discerned in their respective treatments of the pier: where Pott’s pier ends in a folded up gangway, Short’s recedes into an indiscernible point. The low tide in Short’s piece contributes to the feeling of the pier’s abandonment. The closeness and jumbled nature of the ships in the background evoke an image of a graveyard. Skeletal ship masts mirror Pott’s piece, but in Short’s work, they resemble crosses in an old cemetery.

After graduating from the RCA, Pott returned to the school in 1902 to assist Short in the classroom. One account portrays Pott’s dedication to the job and to her students: “‘Enter the class any Saturday morning, and you will find her by the printing press with up-rolled sleeves, in long blue etcher’s blouse, ink-dabber in hand, a copper plate on the heater in front. And while the plate is inked, she will give kind advice as to the botched and bungled plate of the student who stands by.’”

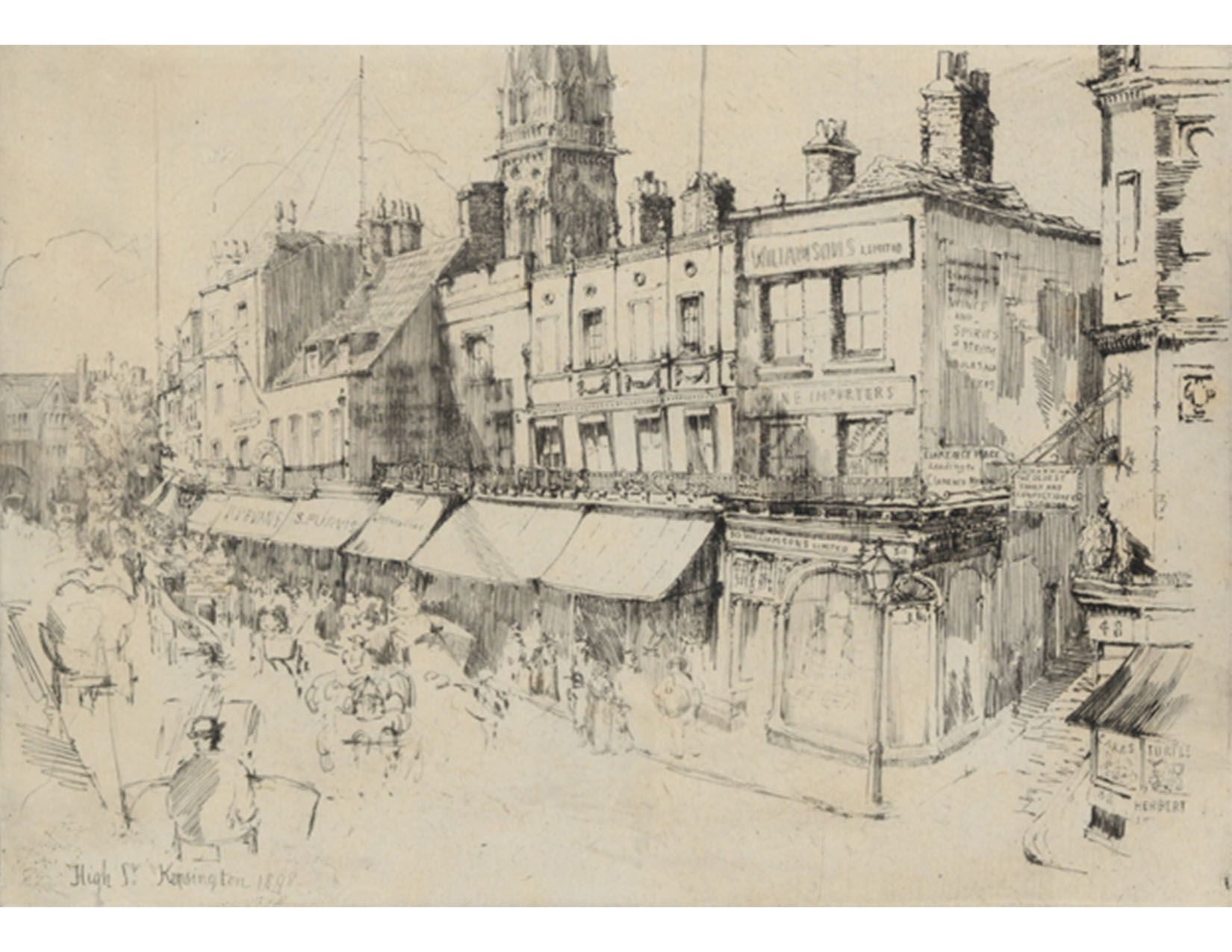

Constance Mary Pott. English, 1862–1957. High Street, Kensington, 1898. Etching and drypoint printed in black on thick, slightly textured, cream-colored paper. The Gladys Engel Lang and Kurt Lang Collection. SC 2016.62.47.

Pott’s work often comments on modernity in relation to the past, regardless of the subject matter. There is a constant allusion to preceding eras in her work, perhaps one of the elements that drew people in and made her so popular. In High Street, Kensington, Pott is not so much concerned for the people going about their daily business as she is about the juxtaposition of the low buildings with their storefronts to the cathedral rising in the background. Everything in this piece seems to pull towards the spired tower, such as the slope of the awnings and the angles of the roofs. This piece lacks the ominous feeling of On the Medway, yet it evokes a certain pang of nostalgia in its clear cognizance of the contrast between days gone by and the present. Pott’s treatment of the cathedral denotes a certain reverence; the tower becomes a reliquary for a bygone time.

Constance Mary Pott. English, 1862–1957. St. Martin's in the field, 1907. Etching printed in black on medium weight, slightly textured, cream-colored paper. The Gladys Engel Lang and Kurt Lang Collection. SC 2016.62.45.

Pott uses a similar approach in St. Martin’s in the Field, giving great detail to the facade of the Church of St. Martin’s in the Field, located in London’s Trafalgar Square. The church has stood there since its completion in 1726, but there has been a church in that space since the thirteenth century. Similar to High Street, Kensington, the people in the piece are secondary. The peddler of flowers becomes especially poignant in considering Pott’s themes; her presence alludes to the ephemeral nature of human activity and the perennial rhythms of human existence. In comparing the three pieces discussed, it is clear that Pott picked out one focal point in her piece – the pier, the cathedral, and the church – and in rendering those central elements, imparted an iconic status to them.

As a print collector’s handbook wrote in 1921, “Every medium of the copperplate is at the command of Constance Pott, whose extraordinary mastery of technique renders service to a rare and beautiful artistic expression.” The writer expressed what was abundantly clear: Constance Pott was a true master. But today, she is largely forgotten.