“It was the Best of Times”: American Prints of the Great Depression

Guest blogger Nicole Viglini is the International Fine Print Dealer’s Association Intern at the Smith College Museum of Art.

This piece discusses works from the The Gladys Engel Lang and Kurt Lang Collection, a collection of prints which was recently donated to the Museum.

Recalling what it was like to create art in the 1930s, Edward Laning, an artist commissioned to paint murals in the New York Public Library by the New Deal’s Works Progress Administration, declared:

Part of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, the WPA was a relief program created during the Great Depression, employing Americans to work on public projects, such as constructing roads, government buildings, and parks. The WPA also hired artists to create art for public spaces like state schools, airports and post offices. Whether or not they were contracted by the WPA, American printmakers during the Great Depression commented not only on the extent of economic hardship people experienced, but also on the social cohesion that came out of the efforts to overcome these tribulations. In addition to portrayals of desolation are depictions of hope, camaraderie and an intermingling of social classes. According to Gladys Engel Lang and Kurt Lang, as the Great Depression wore on, “the more ‘socially conscious’ American printmakers… intended to publicize a ‘deep-going change that [was taking] them… into the street, into the mills, farms, mines and factories. More and more… are filling their pictures with their reactions to humanity about them, rather than with apples or flowers.’”

The amount of work produced by the artists commissioned by the WPA is astounding: between 1935 and 1943, these artists produced around 2,566 murals, 10,000 paintings, 17,700 sculptures, and 300,000 prints. The incredible number of prints produced is owed to the fact that printmaking was relatively inexpensive and the artwork easily transported. “The print itself was the most democratic and educational of any artistic medium,” notes art historian Richard G. Mann, “given that its inexpensive production facilitates the creation of multiple copies which were easily disseminated.”

Elizabeth Olds worked for the WPA’s Federal Art Project from 1935 to 1940, and ardently believed in the mission of the program. She claimed it “‘bridged the gap between the American public and the American artist.’” The FAP commissioned Olds to create Mrs. Manchester’s Musical Program for Homeless Men. In this piece, a woman plays the harp for a group of men. The art conjures a sense of the absurd; it calls to mind the harsh criticism from opponents of the FAP, who found the appropriation of federal funds for art to be frivolous and wasteful. Known for her sharp satire, Olds’s choice to have Mrs. Manchester play a harp acknowledges these accusations. At the same time, she shows the power that art and music has to bridge class divisions. The harp creates a barrier between the men and Mrs. Manchester, signifying the class gulf between them. This divide is accentuated by their body language; each side is pulling away from the other. Yet, some of the audience leans in, perhaps signifying the power that music, and art in general, has to overcome the social gap.

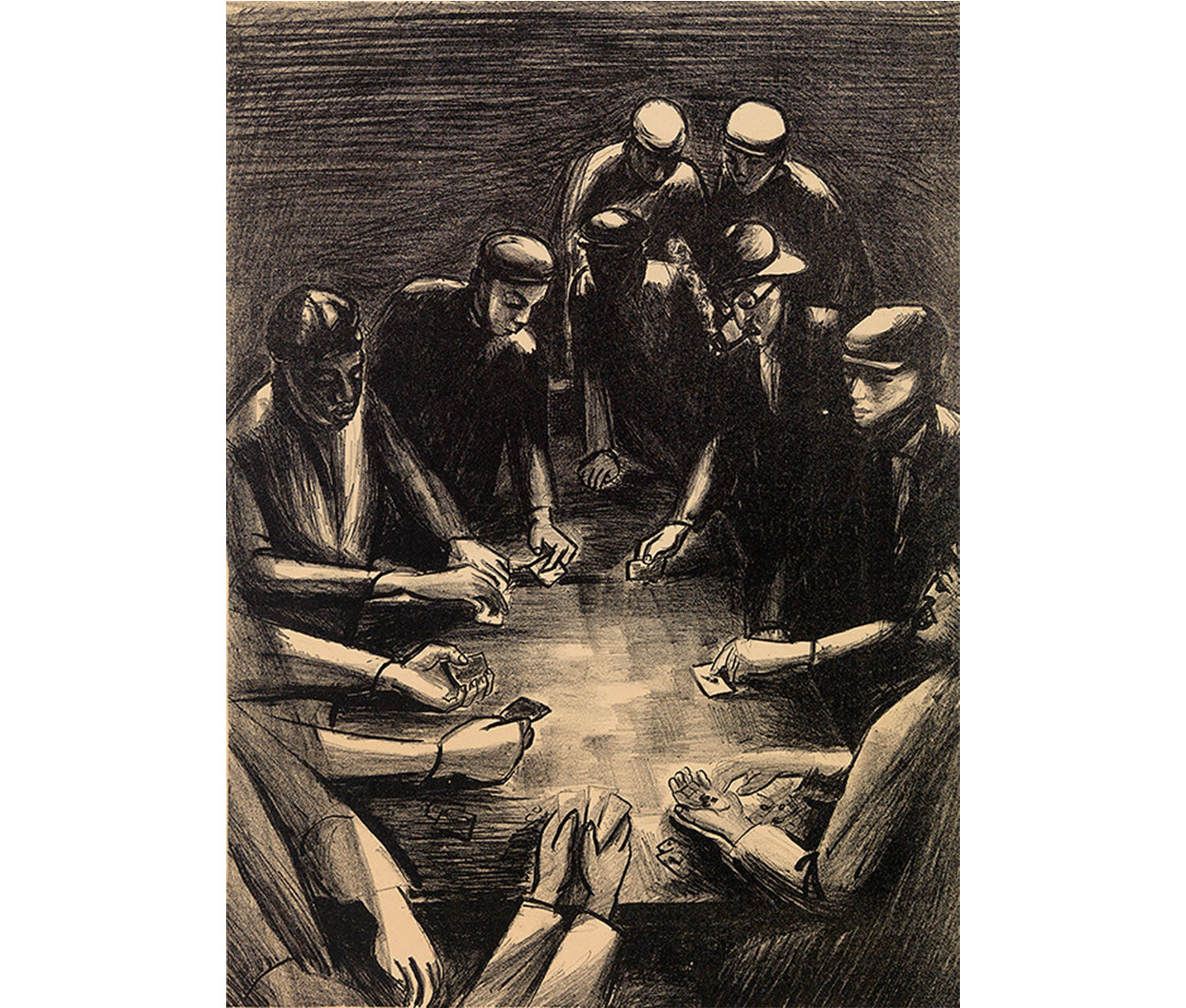

Elizabeth Olds. American, 1896–1991. Black Jack at the Transient Home, 1934. Lithograph printed in black on medium weight, smooth, beige paper. The Gladys Engel Lang and Kurt Lang Collection. SC 2014.32.701.

In Black Jack at the Transient Home, Olds portrays a similar cohesion and camaraderie found in Mrs. Manchester’s Musical Program for Homeless Men. The men around the black jack table stand and sit close together, all engaged in one activity.One of the card players wears a fedora and smokes a pipe; he is clearly from a different social class, yet he blends in with the rest of the players. In this piece, Olds reminds the viewer that people from all backgrounds are subject to the same fluctuations of fortunes. However, while Olds shows a degree of unification among different classes, she does not argue that these distinctions disappeared entirely. In addition to lithographs, Olds began to produce silkscreen pieces under the tutelage of Anthony Velonis under the auspices of the WPA in the late 1930s. After the Great Depression, she taught art and illustrated children’s books.

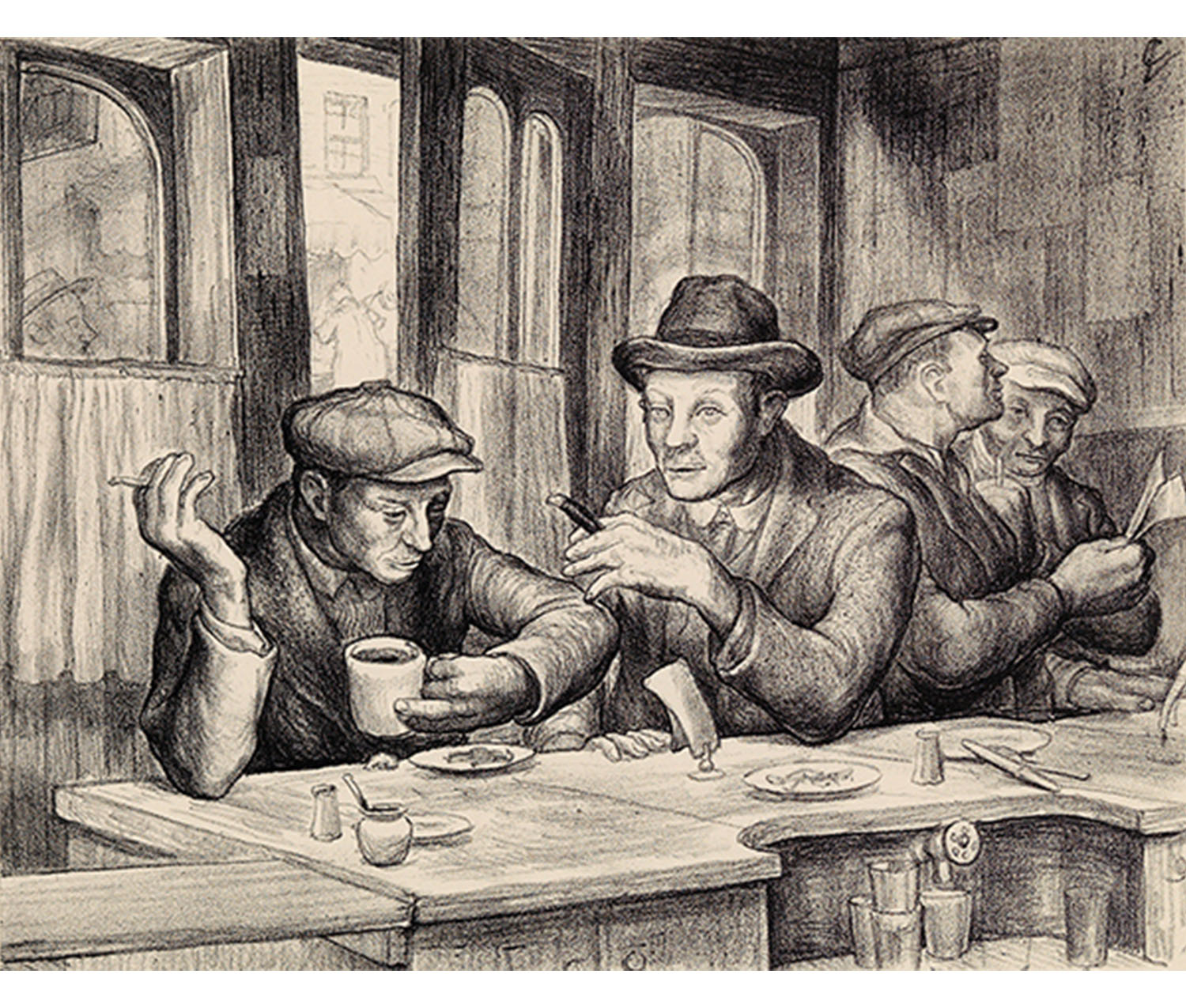

Charles Wheeler Locke. American, 1899–1983. The Hole in the Wall, ca. 1938. Lithograph printed in black on medium weight, slightly textured, cream-colored paper. The Gladys Engel Lang and Kurt Lang Collection. SC 2014.32.582.

Men chat, smoke, and drink coffee in Charles Wheeler Locke’s convivial café scene, The Hole in the Wall. Judging from their caps, the man on the left and the two men chatting at the end of the bar appear to be working class, perhaps longshoremen. The man in the homburg hat smoking a cigar appears as if he hails from elsewhere. This apparent difference of class adds to the intrigue of the piece and allows the viewer to put together a story. As the man with the cigar talks, the longshoreman sips his coffee and gazes at the bill left on the counter, perhaps wondering if the man wearing an expensive hat and three-piece suit will pick it up. Like Elizabeth Olds’s work, Locke’s The Hole in the Wall acknowledges that the economic upheaval of the 1930s spurred new interactions between those from different social classes, yet subtly argues that a class divide still existed. In addition to etchings, Charles Wheeler Locke created paintings, illustrations, and lithographs, often portraying urban scenes and bar scenes. He studied and later taught at the Art Students League in New York City.

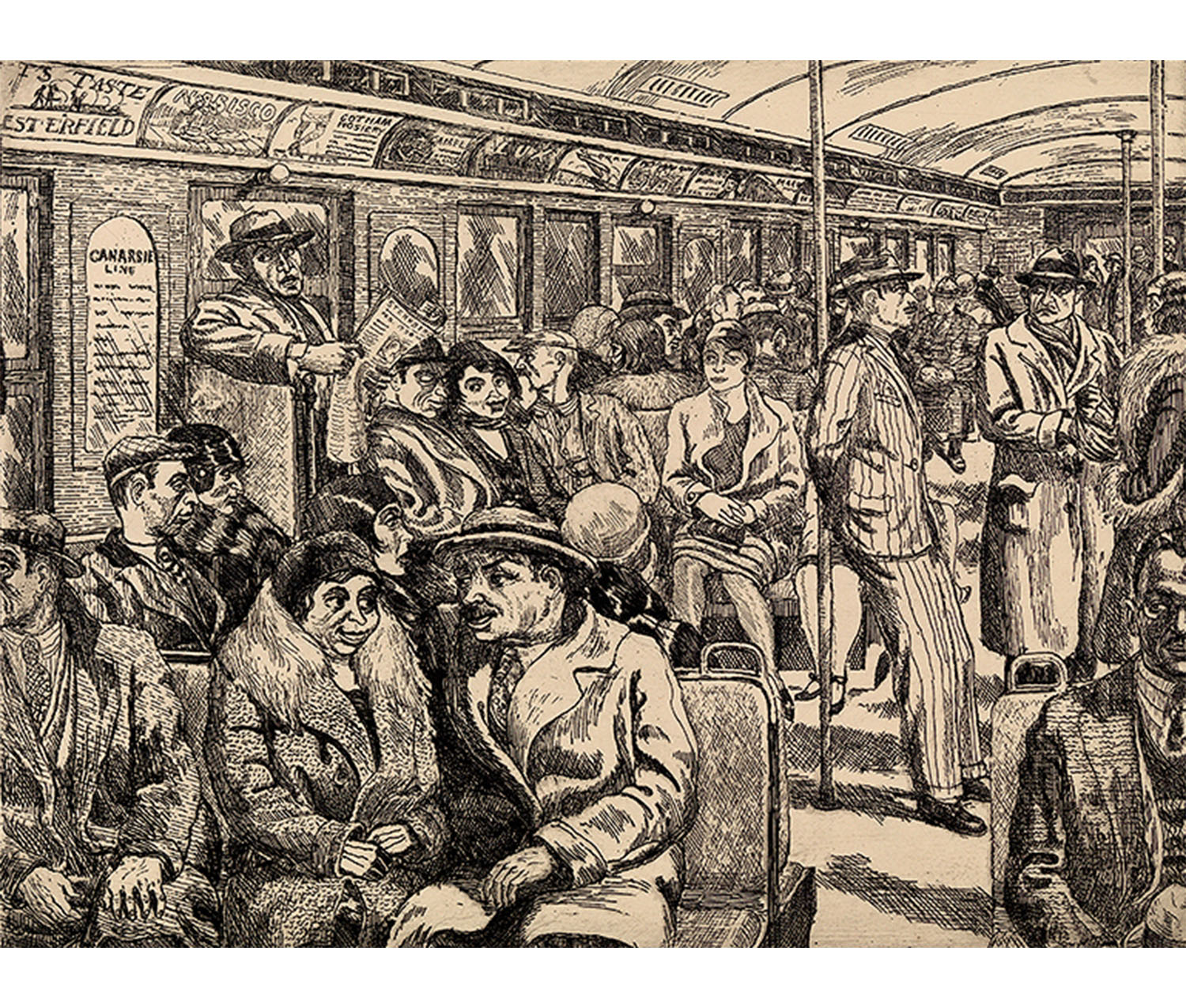

Harry Sternberg. American, 1904–2001. Subway Car, 1930. Etching and aquatint printed in black on medium weight, smooth, beige paper. The Gladys Engel Lang and Kurt Lang Collection. SC 2014.32.717.

In Subway Car, Harry Sternberg depicts a microcosm of New York City. The many people seated and standing in scattered array with their disparate expressions portrays, in condensed fashion, the controlled chaos of a busy city. Just as in the prints by Elizabeth Olds and Charles Wheeler Locke, Sternberg uses peoples’ hats and clothing to convey different social classes. In many ways, the subway is a great equalizer. Everyone aboard is subject to the same fare, the same free-for-all seating and the same delays. Though people from many different walks of life are present together, they do not directly interact with one another. A couple chats in the foreground, and a few shady-looking men look askance; everyone else seems to be absorbed in their own thoughts. The ads above the seats remind the viewer of the busy commercial madhouse above ground. Within the confines of the subway car, hurtling through tunnels beneath the chaotic city, there is a measure of calm and a respite for people to regain some modicum of control. Like Locke, Sternberg also studied and taught at the Art Students League, in addition to working at the Museum of Modern Art and New York University. He worked as a supervisor in the graphics division of the WPA during the 1930s.

In each of the pieces represented in the Gladys Engel Lang and Kurt Lang Collection from the 1930s, there is a wide range of portrayals of life and work. The complexity and uncertainty, the ending of an era and the dawn of a new one with mixed blessings is portrayed in these pieces. The decade of the Great Depression was seen not only as a time of immense strife and hardship, but also as a time for people to come together.