Jo Ortel ’83 on the Work of Truman Lowe

Indigo Casais ’23 is an art history and English double major and a STRIDE scholar working with curator Emma Chubb.

Jo Ortel ’83 is a Smith alumna and the Nystrom Professor Emerita of Art History of Beloit College. She received her MA in art history from Oberlin College and her PhD in art history from Stanford University. Ortel is the author of Woodland Reflections: The Art of Truman Lowe (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2004). Ortel worked closely with Truman Lowe throughout much of his artistic career. Since Lowe’s death in March 2019, she and his family have been placing his art in museums around the United States. In 2020, SCMA purchased Lowe’s sculpture Water Spirit #15 (1991), and received a gift of an untitled related drawing from the artist’s wife, Nancy Lowe.

In this interview, I speak with Jo about her longstanding engagement with Lowe’s work, the relationship between art and the environment, and the changes she has seen in the art world in the years since she studied art history at Smith.

How and when were you first introduced to Lowe and his work? What stuck out to you about his practice that made you want to keep working with it so extensively?

It goes back to another Smith alum, Lucy Lippard ’58. She had written Mixed Blessings (1990), and she wrote it right when I had started teaching down in Texas. I was reading that, and I came across his sculpture through her book. And then when I moved up here to Madison, I started teaching at the University of Wisconsin, in the art department. I taught this big, seventy-person class, and I invited all of the art department studio faculty to come in and talk about their work. Truman came in and he did this slideshow and he was just so eloquent. I saw the whole breadth of his work, and I was really impressed. I already knew that I wanted to continue with a feminist slant and with multiculturalism, and then having him be so articulate about his work was really exciting. That was probably around 1996.

Lowe’s early work is quite varied. He experimented with a range of materials such as ceramics and plastic, as well as installation, painting, and drawing. How do you think he came to settle on wood and specifically wood sculptures as his key medium? What is the significance of wood as a material for him?

A lot of that exploration took place while he was an undergraduate, and then his MFA was all works in plastics, which was hot at the time. I think it was really the year after he graduated from graduate school [1973], when he was teaching in Kansas, where he realized he was a “woodland Indian,” as he liked to say, and he didn’t feel quite comfortable on the windswept plains. That’s when he started returning to the traditional arts and crafts of the Ho-Chunk. His parents made baskets. In fact, I was just at the studio on Saturday and practically tripped over these long, thin strips of wood that Truman’s father had partially prepared for basketmaking, and that Truman had saved when his father passed away. His father would go out and find the right wood and collect it and dry it and cut it, so that his mother could make these beautiful splint-plait ash baskets. I think it was all that knowledge of his father that he just gradually reverted to after graduate school. And he was always combining both Native traditions and modernist traditions. It wasn’t like one took precedence over the other, it was more that they were fusing in his mind, I think.

As for the importance of wood, I think it was in honor of his father, in some ways. But he also talked about how wood is alive, and how wood is water, water is wood.

In your book, Woodland Reflections, you write about Lowe’s ability to evoke water using wood as his material. You also write that “in [Lowe’s] vision, water has larger, metaphorical meanings” (95). What are some ways that you see Lowe’s work alluding to broader themes, such as history, place, or identity?

It sounds cliché when I say it out loud, that whole idea that the river is your life and it runs past you and you see where you came from and where you’re headed. It sounds so trite, but it was really deeply held. The way he talked about it, he genuinely saw nature that way. I think it is that idea of the flow of time, and that we’re all connected. [Lowe] used rivers and streams frequently, and not always in any conscious way. For example, when he talked about art history, he would talk about how there are multiple streams that come together to make the “mainstream.” It’s just a question of, which ones are you going to follow?

He was also interested in looking down into water and how you can see multiple layers. I can’t quite put my finger on it, but I think a lot of it had to do with the fact that he literally grew up on the banks of the Black River, and he was always playing down there. He was always contemplative, and so that idea of thinking about different ways that the river was reflected in his life was important to him.

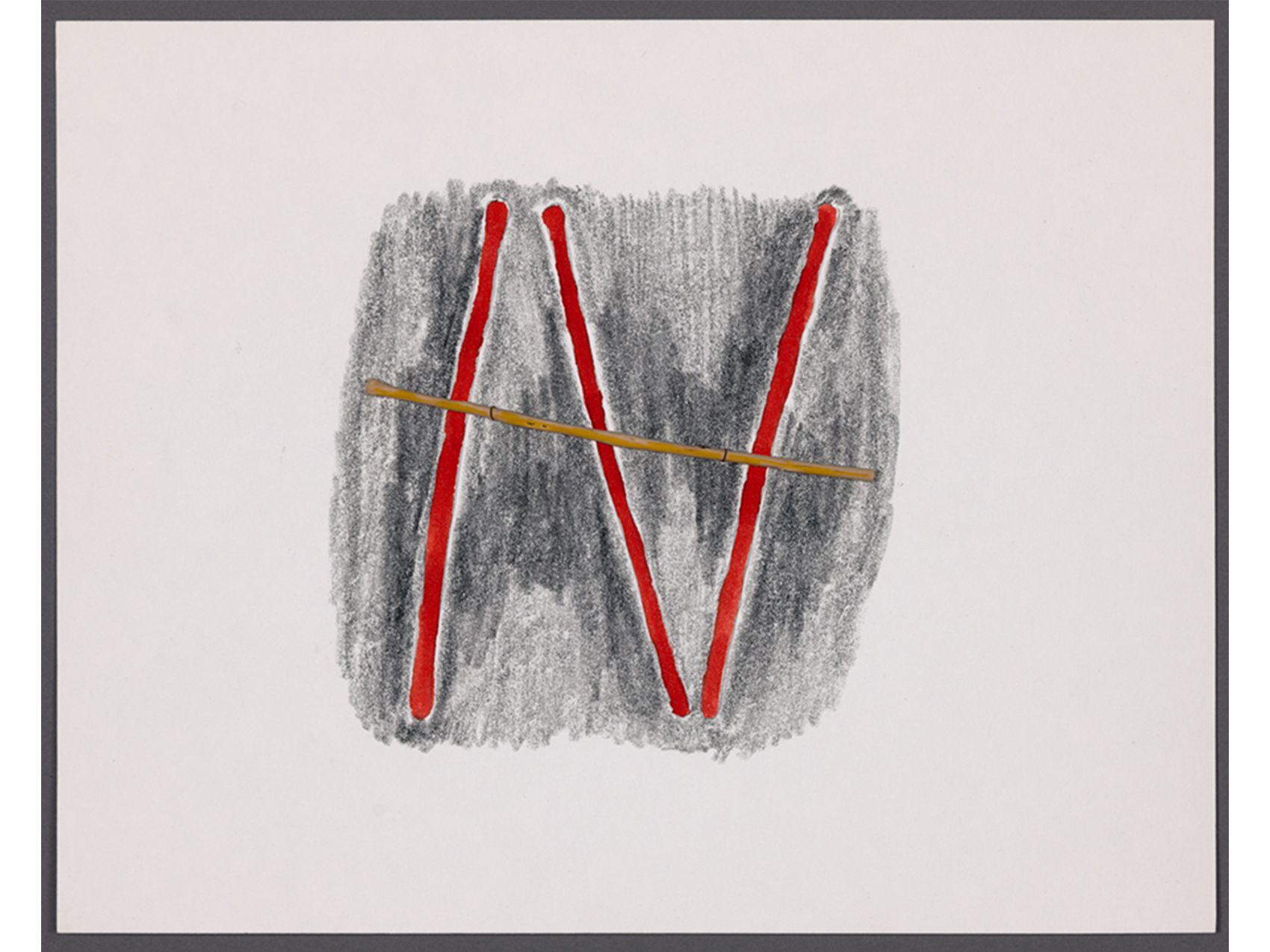

Truman Lowe. Ho-Chunk and American, 1944–2019. Untitled, ca. 1991. Graphite, watercolor, acrylic, peeled willow stick and copper wire on thick, slightly textured, warm white paperboard. Gift of Nancy K. Lowe. SC 2020.22.

Lowe also worked as a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and, from 2000 to 2008, as a curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI). How do you think those experiences shaped his artistic practice, and how do you think his artistic practice shaped those experiences?

I think his practice and his teaching were really intertwined. He would freely give ideas to artists or to students, they would have this conversation. His classes were extremely loose, they were not structured at all. That kind of conversation with students, I think, really fed his creativity as well. It was kind of a back and forth.

As far as being a curator at the Smithsonian, in my opinion, it was a bold and radical move on the part of the National Museum of the American Indian to appoint an artist as Curator. But I think he really did bring a bigger perspective. For example, when I began thinking about doing a book-length study of Truman’s art, he was very supportive—and astonishingly, not for selfish or egotistic reasons. Quite the contrary. He took a broader perspective and said, okay, this is what Native art history needs. We need to have monographs about contemporary artists. When he became curator—or even before he became curator, I think he was consulting with the museum as it was still in its conceptual phases, many years before he became a curator—he really could see that a Native art history, a history of contemporary Native art, needed to be created. That’s what his idea was with the exhibits that he put together for the NMAI. It was really, okay, who are the important figures, and what stories can we start to tell? His idea was that anybody should be able to write about this, not just Native people, but he wanted to point in some directions.

You have been working with Lowe and other Native artists for a long time. Have you seen a shift in how museums approach Indigenous artists and their work?

Yes and no. I’m surprised that some museums are still not diversifying their collections and their programming, but then in other cases, they really are. When I first started thinking about this area in the 1990s, it was really a question of raising the visibility of Native artists within the discipline of art history—putting the spotlight on the Native artists, giving them shows, and examining how institutional racism and sexism work, the mechanisms by which such biases are perpetuated within the discipline of art history and in the art world generally. Now, I think, maybe within the last eight or nine years, it’s shifted more to, okay, we don’t need to put the spotlight on Native artists anymore. Rather, it’s important to get them into the main galleries, to not be marginalized within the galleries. That’s why getting his work, or any Native artists’ work, into permanent collections is important to me.

Nature was clearly an important part of Lowe’s art, as well as his life in general. You also do a lot of work at the intersection of art and environmental studies. How do you think these two fields impact each other, both in educational and artistic settings and beyond? What do you see as the potential for this intersection going forward?

Truman has opened up my eyes to see nature differently. Now that I’ve seen it in his work, I find things, like red branches in the snow in the springtime, it’s just amazing. In that sense, he really has influenced my vision of nature and the environment.

I have to say, I have very little time anymore for art that hangs politely in museums. I really think that there has to be some connection with the current issues, and the environment seems, to me, to be among the most important. This is that idea of how the art world and art history move forward. That transformation into looking at other kinds of art than just painting and sculpture is going to be important.