Journey on the Ship of Fools: From the Republic to the Butcher’s Bill

Guest blogger Hannah Goeselt ’20 is a former Cunningham Center student assistant.

The best thing about having worked in a museum archive is that every object has its own history, of how it got here, its provenance, and the story of why it was made. Some also tend to straddle the line between art and archival object, where somewhere along the line of that history an image was taken out of its functional context to become art. A great example of this change in status is the history of single leaves from rare books being acquired by museums (and libraries), changing the way we view them from part of a whole, textual, object into a visual example that stands on its own.

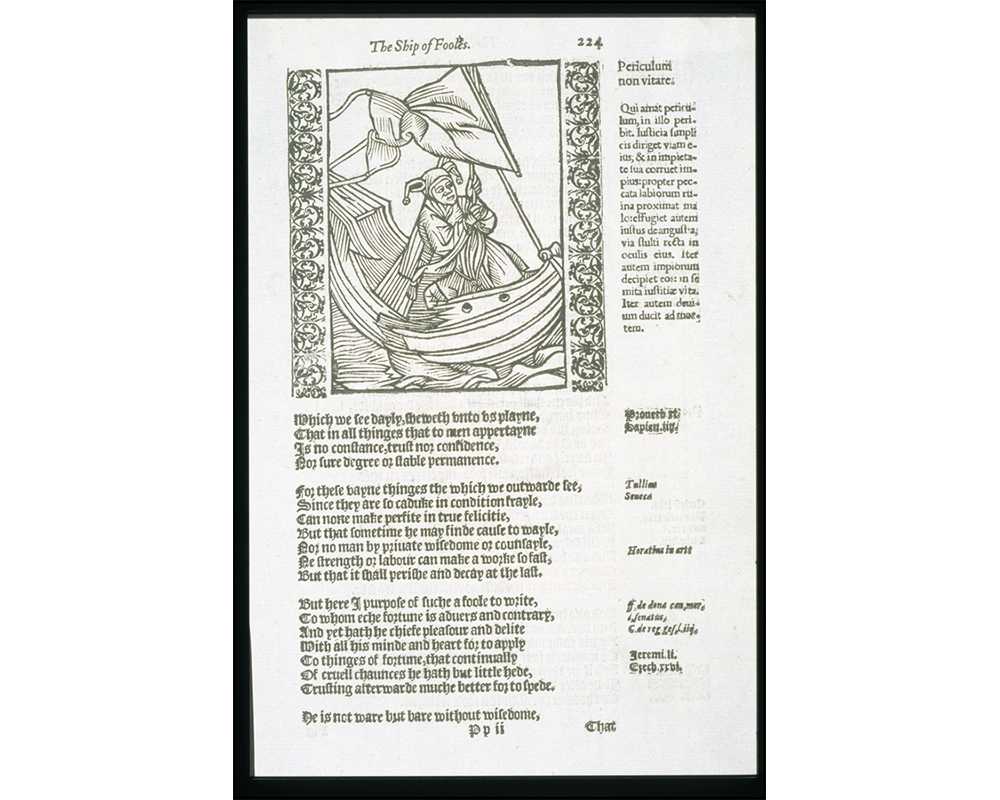

We begin with the image on the page (above image), our eyes immediately straying to the window sandwiched between two columns of ornamental borders and depicting a robed figure standing in a comically small boat, tugging on a sailing line while the sail itself flaps uselessly in the breeze. The boat has a wide crack in its side, though the figure appears unaware, even unconcerned by the whole affair. On his head he wears a hood sewn with cloth shaped like donkey’s ears that end in a bell dangling from the tips, commonly worn by a court jester, or a fool. This visual assertion is backed up by the phantom book’s heading above proclaiming it to be “the Ship of Fooles," page 224. Below reads as follows:

In order to understand what we are looking at, we must first back up some 2400 years to Book VI of Plato’s Dialogue known as the Republic. Within, a parable set down by Socrates compares a government with a poor leader to a ship with an incompetent captain, and his crew the rabble of the polis. When this captain is overthrown by his crew, they set about drinking and eating; no one is a very skilled navigator, and the ship is left to sail about aimlessly.

When the Republic was finally translated to Latin during the first half of the fifteenth century, it was done not once but three times- and it did not take long for Europe’s intelligencia to start adapting the new material into their own works, as the Humanist movement hungered for any and all ‘rediscovered’ works of Antiquity that were becoming available. In 1494 the Republic and its imagery of a boat led by a sailor mob would be the inspiration behind German humanist Sebastian Brandt’s (1457–1521) satirical creation Das Narrenschiff, The ship of Fools.

Brandt would take Plato’s allegory a step further to encompass the entire state of human affairs, and was the first to print a book that included both contemporary events and people living at the time of publication. Das Narrenschiff was divided into 112 stories relating the activities of various types of fools, a narrative device in which a jester acts as a metaphor for a specific vice or weakness in a person. Accompanying these tales were a series of woodcuts depicting a range of fools doing various ill-considered activities. These are thought at least in part to have been the work of a young journeyman Dürer. Our own image is in fact a copy of a copy of Dürer’s print depicting a fool unaware of his misfortune in Chapter 109 of Brandt. If placed side by side, you can see how our printmaker tried to imitate the curving lines and compositional layout in the original, though the end result comes out as simplified, lacking the finesse and detail a more experienced artist might achieve.

The text, however, is not Brandt’s German verse, but rather the 2nd edition (1570) of Alexander Barclay’s “Shyp of Foles of the Worlde”, a loose English version of Das Narrenschiff made in 1509. You can see to the right of our sailor an additional text: the corresponding narrative for the Stultifera Navis, a Latin translation by a student of Brandt’s. Barclay (ca. 1476–1552) used this version in creating his own verse, producing less a word-for-word translation and more of an interpretation of the original, aimed at mocking 16th-century fools of English origin rather than Brandt’s more general moralization. It probably would have been easier for him than consulting the original German, as Latin was the international intellectual language shared across Europe and therefore more familiar. Stultifera Navis and Shyp of Fooles were only two among seven translations of Das Narrenschiff within 15 years of its publication, attesting to its extreme popularity in its own time and for centuries to come. In fact, the book sparked an entire genre of Fool’s literature in Europe during the late 15th through 17th centuries. The works were a medium for critiquing dominant institutions like the Church by adopting the affectations of a court fool. In addition to Barclay’s English version of the text, some famous examples of this genre are Hieronymus Bosch’s Ship of Fools painting and to a smaller extent Erasmus’ In Praise of Folly.

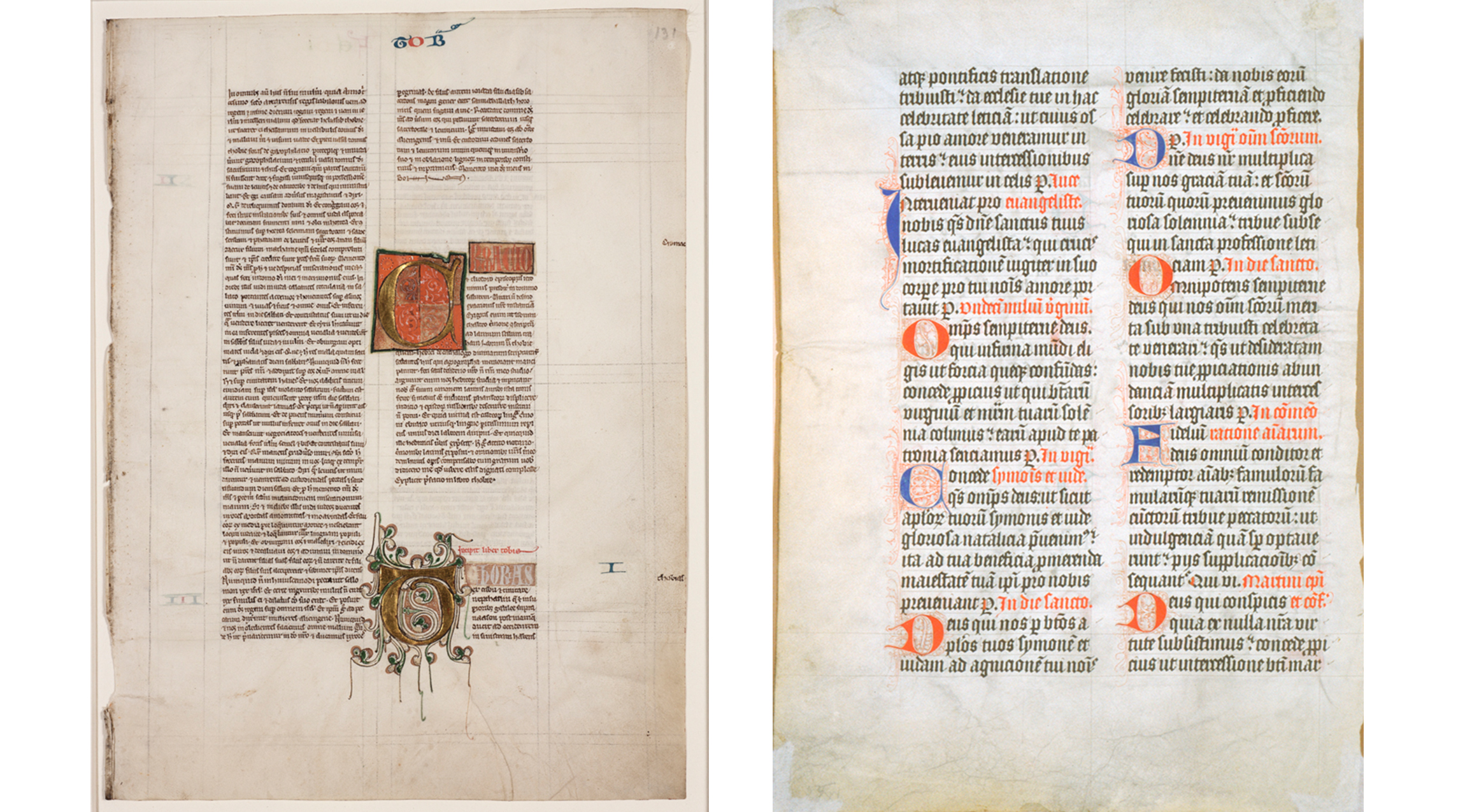

But why is the page of a book, a small piece of its greater whole, presented here as a standalone art piece? For that we must reach into the file cabinets of the Cunningham Center, where we keep the object files on all works on paper (and paper adjacent) stored in the archive. Using this, we learn our book page was bought in a group of eleven different leaves from Northampton’s legendary Hampshire Bookshop in 1950. Though an independent bookstore, the business was intimately linked with Smith College, founded by two alumnae with many more on its board and as staff. Out of the purchase, the SCMA received a leaf from a 1525 copy of Pliny’s Natural History, a 1493 Liber Chronicarum, a 1527 edition of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and seven medieval manuscript leaves from Books of Hours, Psalters, and miscellaneous liturgical books (see 1950.147, 1950.143, 1950.146, 1950.145, 1950.144, 1950.148, 1950.150). It is the manuscript leaves that first give away where these pieces come from, as several are immediately identifiable as leaves whose parent manuscripts were used as source material in portfolios from the Ege collection.

Left: Unknown. English. Manuscript Leaf, from a Vulgate Bible, ca. 1200. Ink and gold on vellum. Purchased. SC 1950.147.

Right: Unknown. Flemish. Manuscript Leaf, ca. 1475. Ink on vellum. Purchased. SC 1950.150.

Otto F. Ege (1888–1951), faculty and dean of Cleveland Institute of Art and self-proclaimed “biblioclast”, or book-breaker, is responsible for over a hundred manuscripts being dismembered in the 20th century. His business excluded the dismembering of any early books or manuscripts that were ‘museum pieces’, as he termed it (ironic then to have the fruits of his labors end up in museums), but for the most part involved much slicing of pages out of the binding and mounting them on cardstock, with a printed label outlining some information relevant to the leaf. These were further organized into teaching portfolios created for the purpose of selling to institutions across the country.

One of Ege's labels. Photo courtesy of Hannah Goeselt.

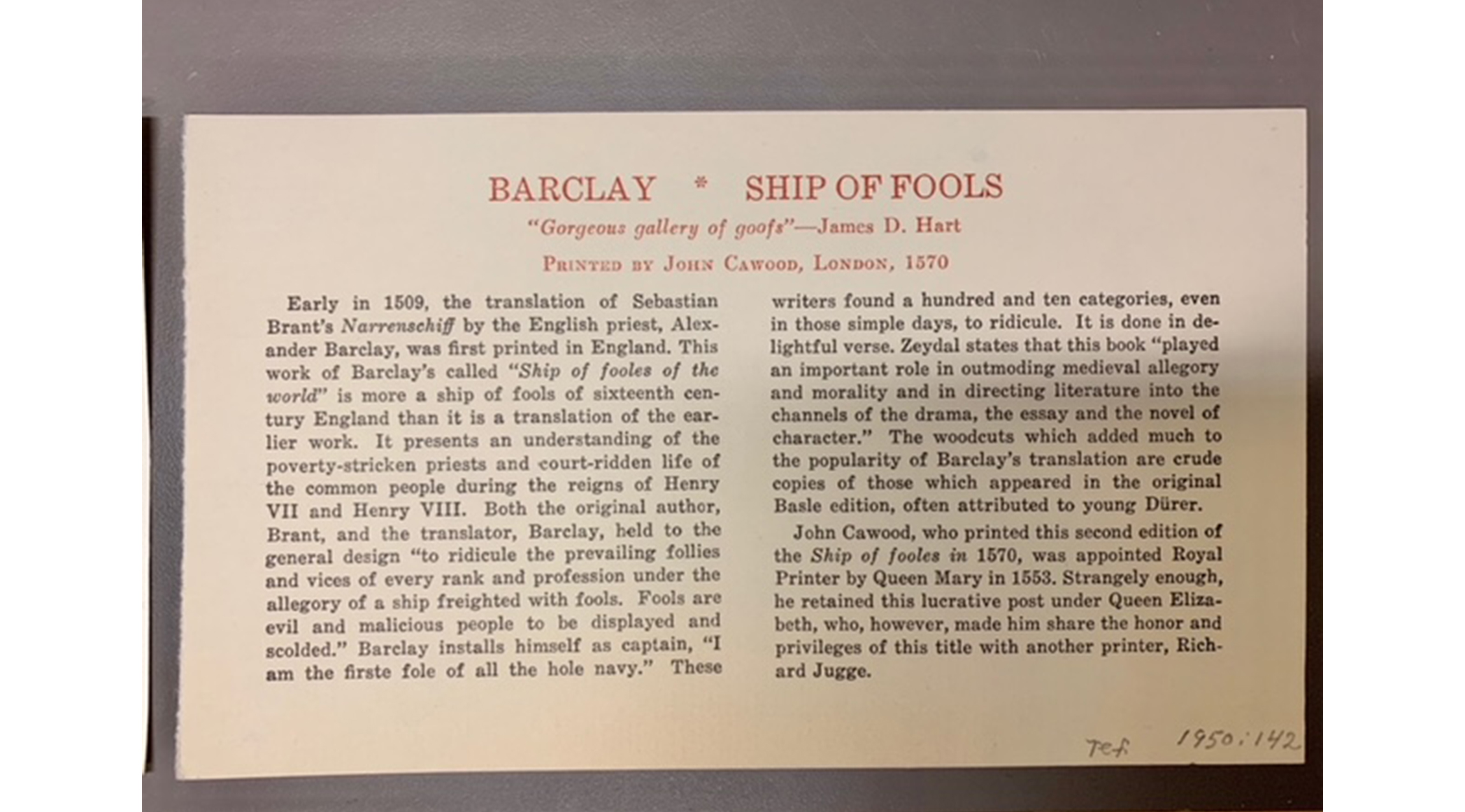

One particular series, titled “Original Leaves from Famous Books: Nine Centuries, 1122 AD–1923 AD," shares many examples of leaves from the same printed books as the Smith collection bought in 1950. This further strengthens our theory for the origin of this grouping, but the final nail in the coffin lies again in the object files. Here, we have two surviving text labels that provide historical anecdotes for our Barclay (an italicized quotation from the scholar James D. Hart exclaims “gorgeous gallery of goofs”) and Pliny’s Natural History. Their layout is very distinct and consistent with Ege-made labels for FBNC (Famous Books Nine Centuries) portfolios. Most likely, this is a random assortment of leftover loose leaves for individual sale, though the printed leaves must have been involved in the process of creating a FBNC set in some capacity.

All of this is to say, the museum label is only the tip of the iceberg in a museum, the deep and often strange context not immediately presented to the average gallery-goer. I find that often it is beneath the water that some of the most interesting information becomes available. With that in mind, how is your experience interacting with the artwork affected by knowing some of its background? Has your perception of our intrepid sailor changed in any way?