Käthe Kollwitz: Darkness and Light

Amanda Shubert is the Brown Post-Baccalaureate Curatorial Fellow in the Cunningham Center for the Study of Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945) was a German printmaker and sculptor. The first woman admitted to the academy of arts, Kollwitz flourished during the Weimar Republic. Her fortunes changed after Hitler came into power and she petitioned against the Nazis. She lost her studio and was forced to leave the academy. Kollwitz’s commitment to social justice permeates her graphic work, particularly in her portrayals of the working class, the poor, and the effects of war.

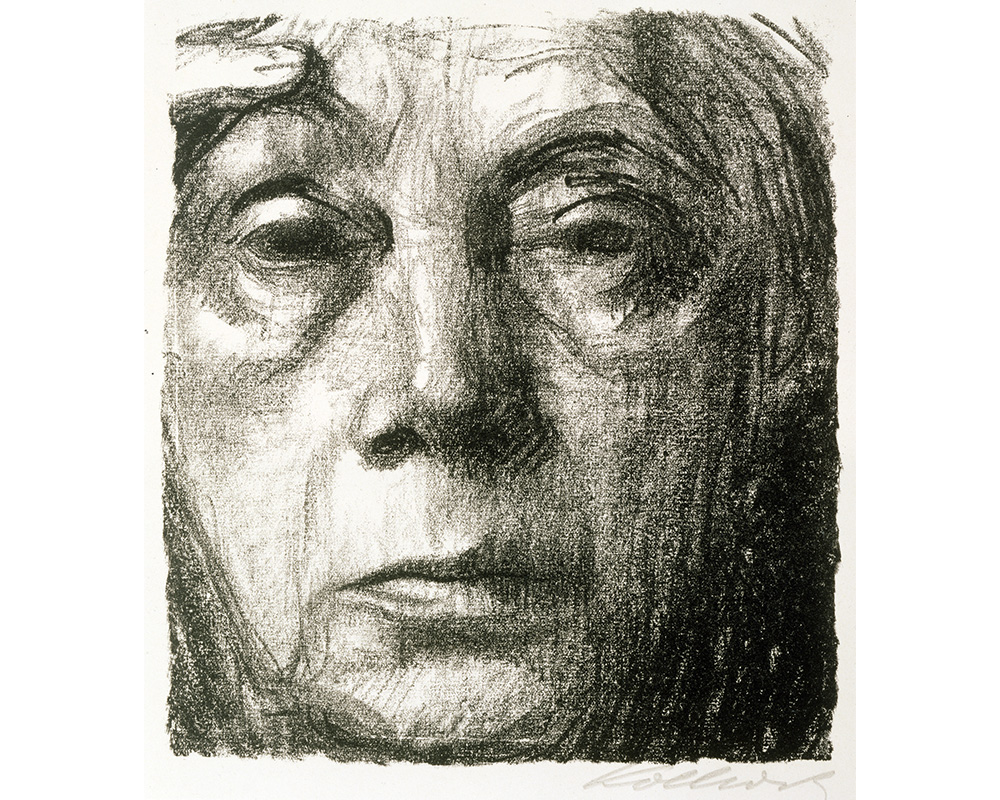

Kollwitz’s prints are haunting, unsettling and provocative, but even as they show scenes of suffering, pain, death and loss, they are not unrelentingly grim. Empathy suffuses Kollwitz’s work, as though art were a way of identifying faces among the masses, drawing them out of anonymity. The sense of figures drawn out of darkness is also a compositional idea in Kollwitz’s prints. Often shrouded in dark, shapeless clothes, her figures come to life in their faces and hands, both communicators of feeling and experience. Take a look at this print called Battlefield, from the series The Peasant’s War:

Käthe Kollwitz. German, 1867–1945. Schlachtfeld (Battlefield), Plate VI from series Bauernkrieg (The Peasants' War), 1907. Etching, mechanical grain, aquatint and engraving on paper. Gift of Mrs. John Wintersteen (Bernice M. McIlhenny, class of 1925). SC 1957.80.

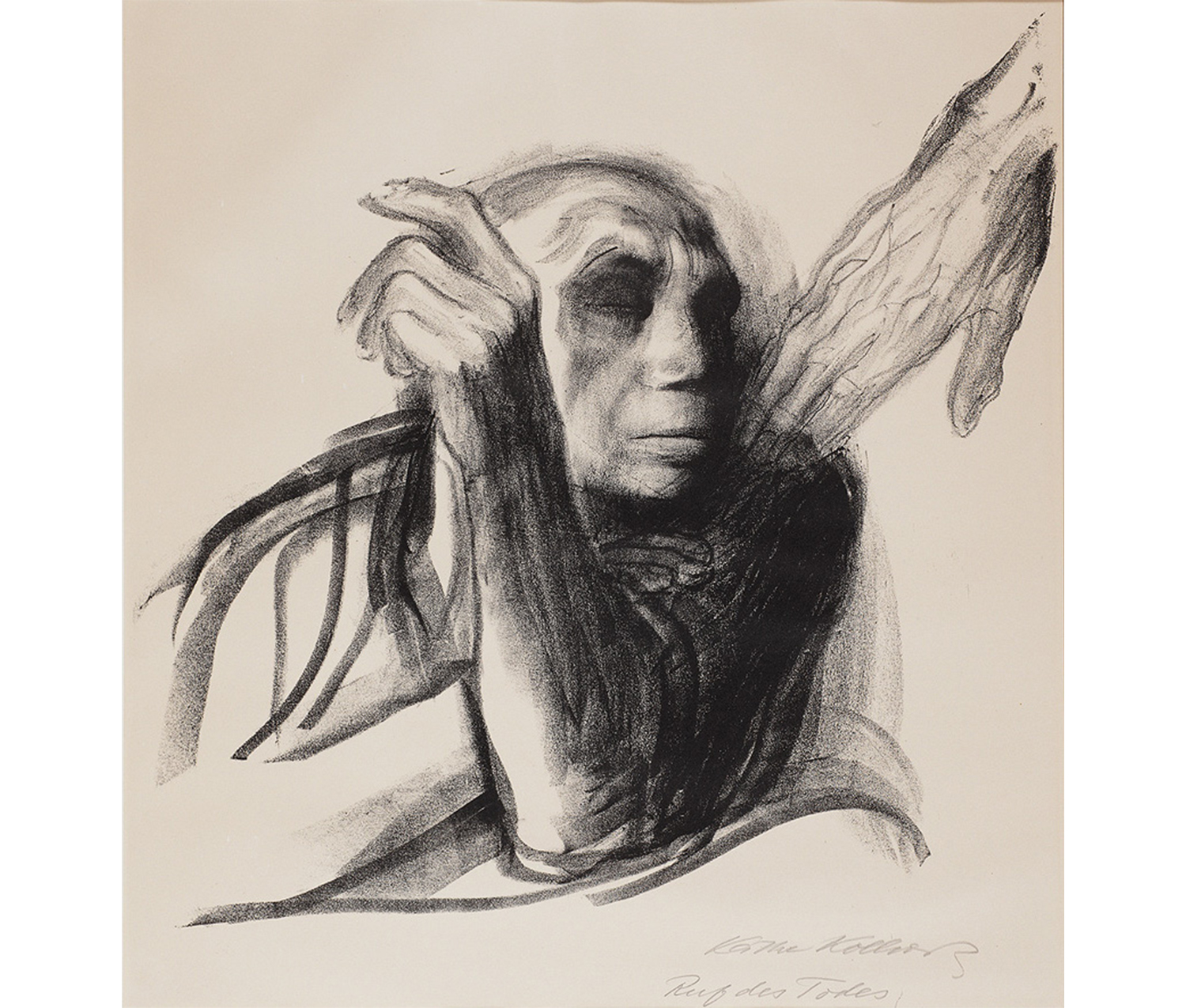

In the dark of night, a woman holding a lamp searches for a face she recognizes among the dead. (Given Kollwitz’s frequent depictions of mothers and children, I always imagine this woman is looking for her son.) Notice the dramatic illumination of her hand and the man’s face. I love the expressive use of shadow, light and tone in this print that allows Kollwitz to picture this interaction between the living and the dead, the hand and the face. Kollwitz’s art is, in a sense, a recovery of the dead: like the woman seeking her son, she shines her lamp on the obscure, the victimized and the suffering. This act of bringing light to darkness is, I think, both an act of empathy and of political engagement. She lends dignity to the sufferers and gravitas to those willing to face difficult truths. Her lithograph Call of Death suggests that facing death, even facing one’s own death, can be a moment of connection.

Käthe Kollwitz. German, 1867–1945. Ruf des Todes (Call of Death), 1934–1935. Lithograph printed in black ink on cream colored wove paper. Gift of Mary B. Mace, class of 1935, in memory of Jere Abbott. SC 2003.29.2.