Lawdy Mama (1969): Celebrating The Ordinariness of Black Women in ‘Black Refractions'

Camille Bacon is an Africana Studies major and member of the Class of 2021. In this post she reflects on a Barkley L. Hendricks painting from Black Refractions: Highlights from The Studio Museum in Harlem, which was on view before the museum's closure.

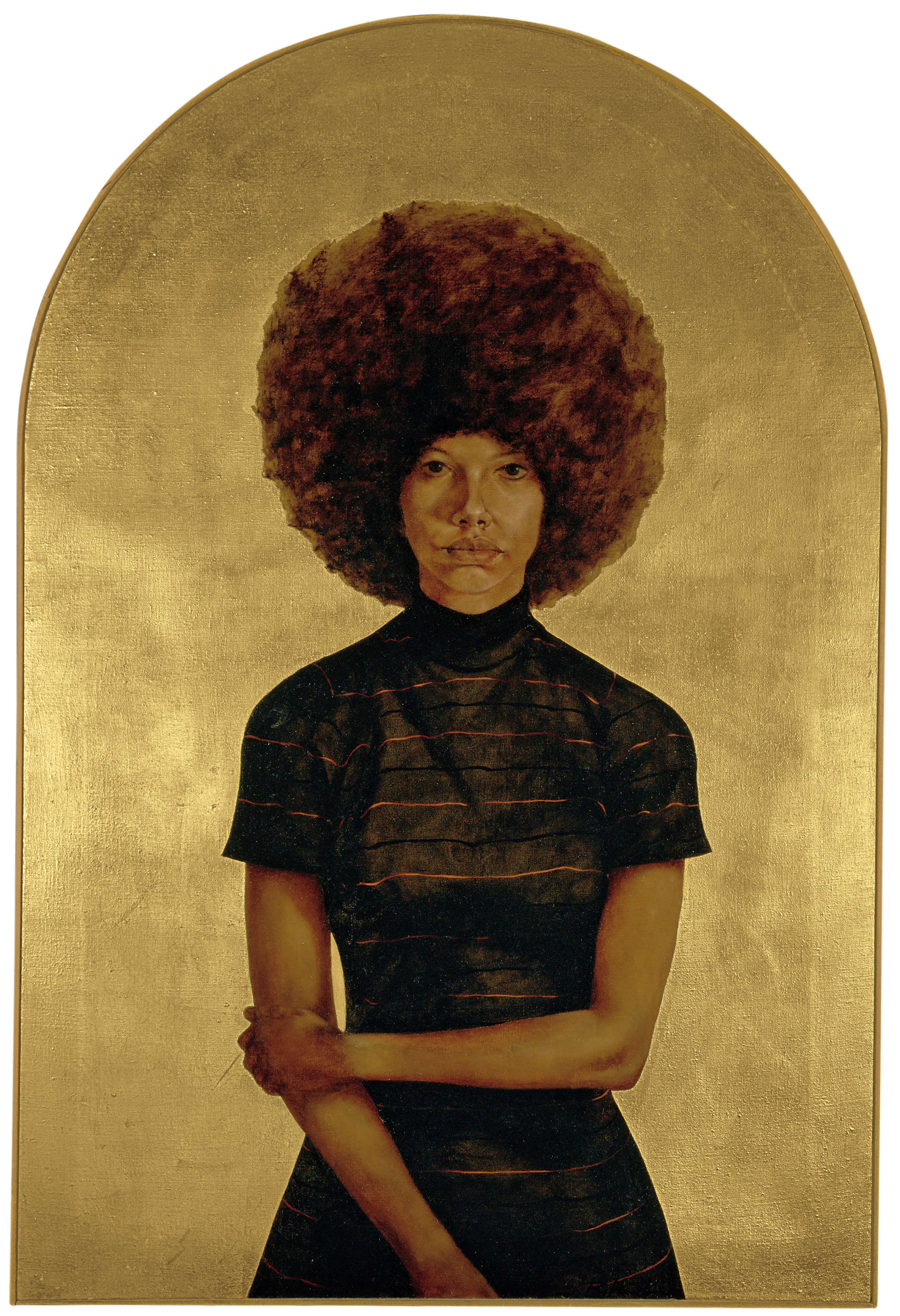

Almost 50 years after its creation, Barkley L. Hendricks’ iconic masterpiece ‘Lawdy Mama’ sits gazing out over the facade of The Smith College Museum of Art, inviting onlookers in with a soft gaze. When I first encountered Hendricks’ piece, which has arguably become a motif of black contemporary art, I was struck by the subjects ordinariness. I got the sense that she could be any black woman — she could be my mother, my friend, my teacher... she could be me — looking at the piece gave me the sense that I, along with the other black women I know, had finally been seen. And now I wonder, what does the existence of a piece like Lawdy Mama mean in a moment that demands excess from black women?

Infused with the poison of anti-black racism, popular culture insists on depicting black women one dimensionally. We appear as pillars of strength (think of the women in Black Panther, tasked with defending the kingdom) or as disparaged victims of our circumstances (think of Viola Davis as Aibileen Clark in The Help). Little room has been left for a complex and nuanced black female subject in visual art. Scholar and cultural critic Nicole Fleetwood argues that polarized renderings of black women (as either superhuman or sub human) are damaging because they obliterate any possibility of returning to an ethical and humanizing representation of a black female subject.

By placing both the ordinary and the iconic within the boundaries of his frame, Hendricks swings the representational pendulum back to center. A simple cotton dress and modest pose saturates his subject with normalcy. What does it mean to veer away from opulent attire and an eye catching pose such as hands-on-the-hips that could make the subject look more queenly... more “worthy” of celebration?

Hendricks' subject could be any black woman caught in an intimately regular moment: getting ready for work, on the way to the store, waiting for the bus, posing for a photo -- or trying to be while a friend is giggling on the other side of the lens. This is a woman we could encounter anywhere in our daily lives, giving her a sense of universality. And Hendricks makes a point in asserting that despite her normalcy, this subject is not only deemed important enough to paint, but to appear dignified and celebrated within a frame.

In a subtle stroke of genius, Hendricks juxtaposes the subject's mundanity by uplifting his plain-jane subject as if a deity. Her expansive afro gathers divinely around her head, as if forming a halo. A rounded frame alludes to Byzantine and Orthodox imagery of culturally relished religious icons. The gold background makes the subject appear regal, like a monarch. In this sense, Hendricks seems to be saying “all black women deserve to be celebrated, just the way they are.”

Comments

I appreciate this

Thank you for this insightful reflection. I loved reading this.