Leonard Baskin and Barry Moser

Guest blogger Renee Klann is a Smith College student, class of 2019. She is the 2015-2017 STRIDE Scholar in the Cunningham Center for Prints, Drawings, and Photographs. This post discusses the art of Barry Moser, an printmaker and professor at Smith College. A recent gift of 91 of his works was made to the museum by Jeff Dwyer and Elizabeth O'Grady.

Leonard Baskin and Barry Moser were both typographers and printmakers who lived and worked in the Pioneer Valley. Initially Baskin was a mentor to Moser, but over time the two became peers with distinct styles and subjects.

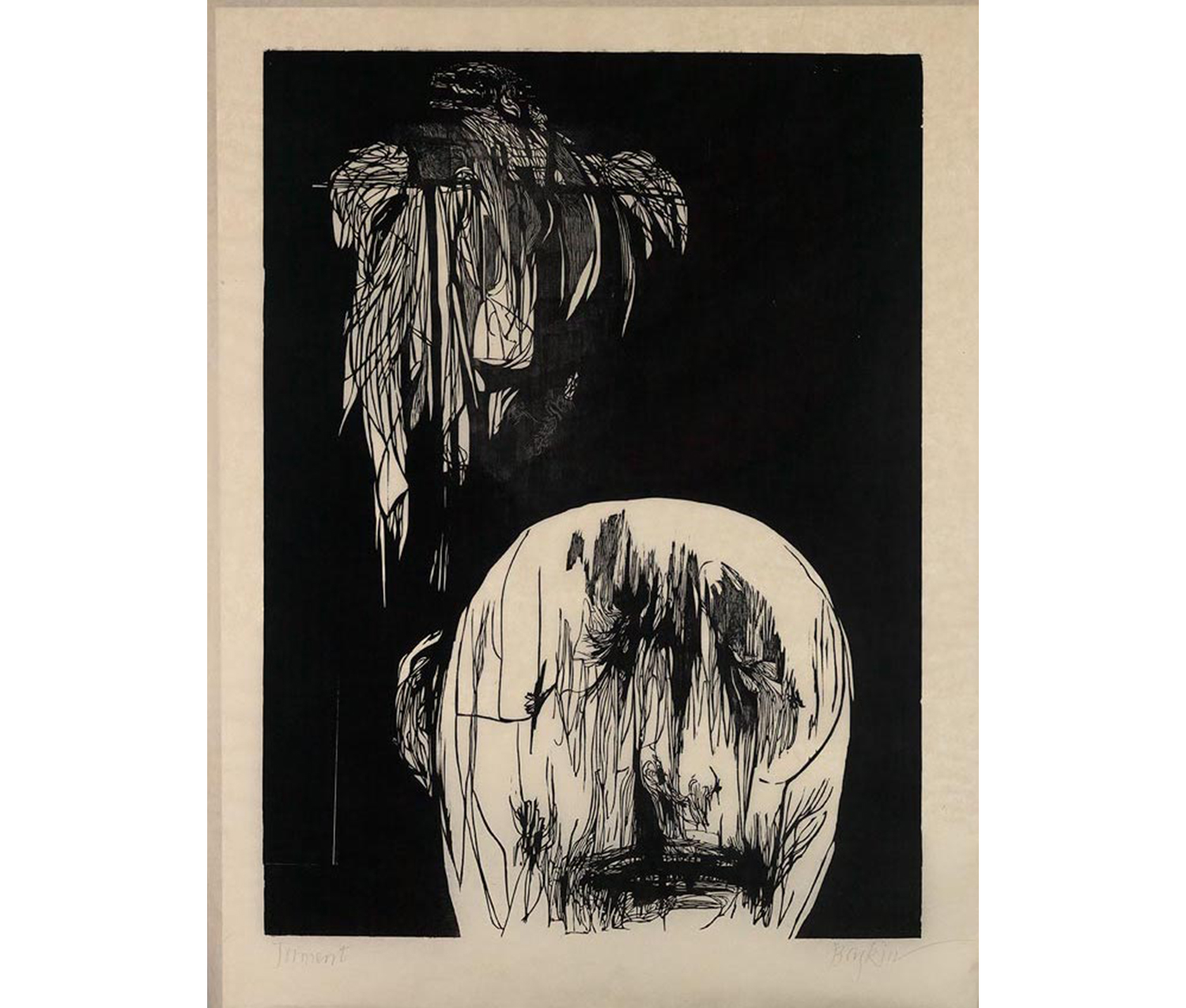

Baskin was the son of a rabbi, and religious and mythological imagery were major influences on his work. Although abstract expressionism was the dominant artistic style at the start of his career, Baskin preferred to make representational art. He claimed that the human figure “contains all and it can express all,” and aimed to depict the human condition in his work. His view of humanity was influenced by his service in the Navy during World War II and the cruelty he saw people inflicting on each other. Baskin didn’t shy away from portraying frightening and painful subjects because he wanted to show viewers what was wrong with the world.

Great Bronze Dead Man is an example of Baskin’s focus on the human body’s expressive possibilities. The figure’s facial features are not sculpted in much detail, so he could be anyone, and the rough, wrinkled cloth wrapping hides his body, making him a solid, imposing form. He is an ambiguous presence reminding viewers that death is inescapable but not necessarily horrifying.

Leonard Baskin. American, 1922–2000. Torment, 1958. Woodcut printed in black on thin cream Asian paper. Gift of Paul Seton in memory of Cynthia Propper Seton, class of 1948. SC 2011.24.4.

Leonard Baskin. American, 1922–2000. Tobias and the Angel, 1958. Wood engraving on paper. Gift of Priscilla Paine Van der Poel, class of 1928. SC 1977.32.35.

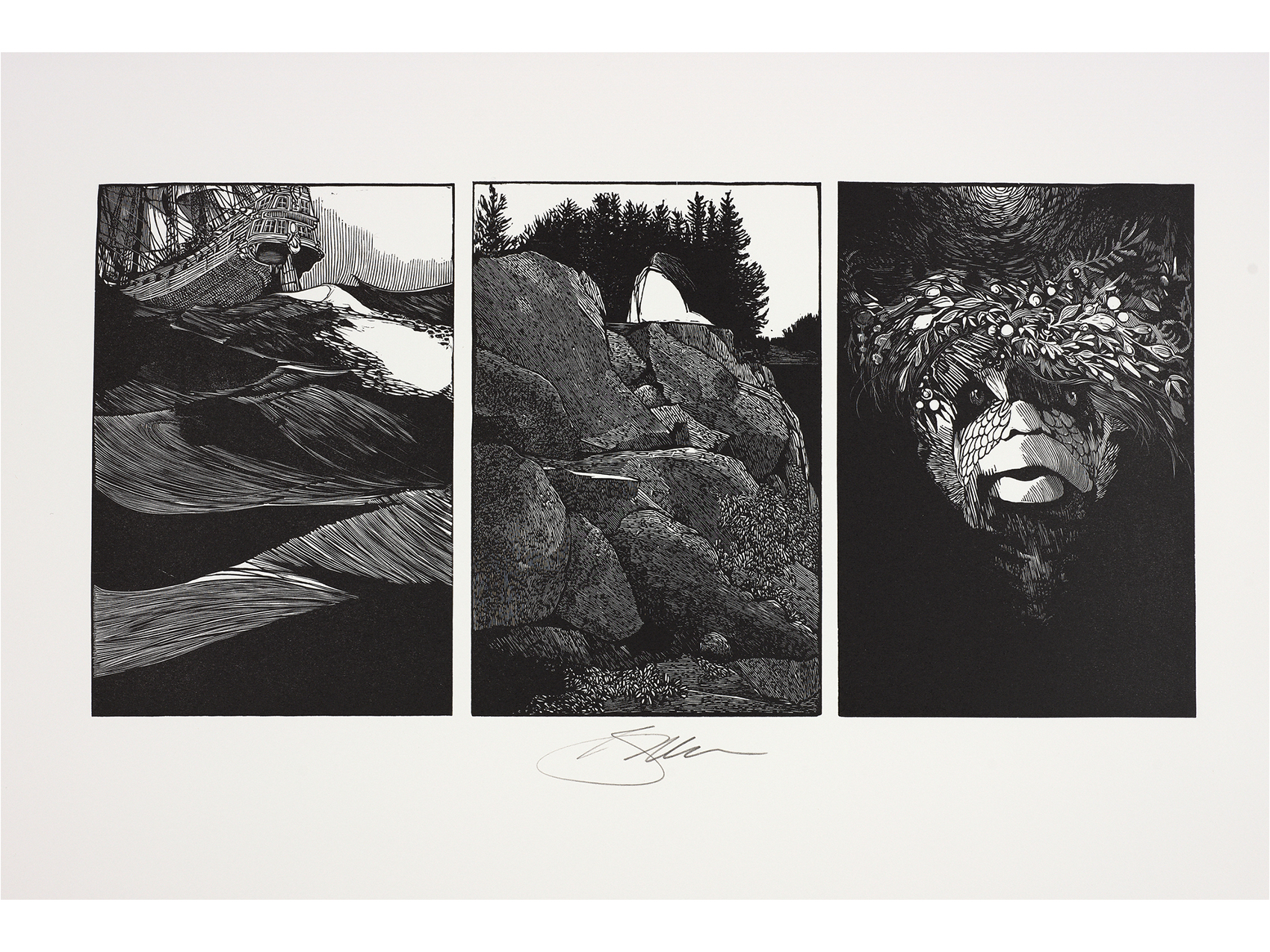

Although Baskin considered himself a sculptor first, he was also a skilled printmaker, and published fine-art illustrated books at the Gehenna Press in Northampton. His wood engraving Tobias and the Angel depicts a story from the biblical Book of Tobit, in which an angel appears to the boy Tobias and tells him to use the heart, liver, and gall from a fish to make a cure for his father’s blindness. The landscape in the print is bleak and the figure of the angel is dark and almost frightening, but he is a benevolent figure trying to help Tobias. Baskin’s work continually incorporates this tension between good and evil, suffering and hope.

Barry Moser began to admire Baskin’s work as a college student. He was particularly struck by Baskin’s wood engravings, which inspired him to try the medium for himself. Moser later recalled that he was “trying, with little success, to get a handle on that devilish medium by emulating Baskin’s style.” A few years later, Moser moved to the Pioneer Valley and was introduced to Baskin, who agreed to informally teach him. Baskin told him to get a pen with a fine point and a rough sheet of paper, and to go draw a tree from life. When Moser returned with the finished drawing Baskin was unsatisfied. He told Moser to try again. Moser had about six “terse and remarkably brief” meetings with Baskin over the next few months, and each time Baskin told him to redraw the tree. These unconventional lessons taught Moser to pay attention to materials and craftsmanship and not to settle for mediocre work.

Although Moser never had specific lessons from Baskin on wood engraving, he called Baskin “a huge influence on me. A powerful influence that was difficult to get out from under.”

Barry Moser. American, born 1940. Phorkyads, 1971. Wood engraving printed in black on thin, slightly textured, white laid paper. Gift of Elizabeth O'Grady and Jeffrey P. Dwyer. SC 2016.65.112.

One of Moser’s fairly early works, Phorkyads, displays a similarity to Baskin’s style of cutting. The Phorkyads were three mythological sisters who shared one eye and one tooth among them. They lived in a dark cave because they were too monstrous for the sun or moon to look at. The visual similarity between Moser’s Phorkyads and Baskin’s work stems from the grotesque nature of the faces and the web of black lines that define the facial features. This texture creates recalls the texture of creased and pitted skin, and the contrast between the smooth white foreheads with the black eye sockets effectively emphasizes the repulsive nature of the Phorkyads.

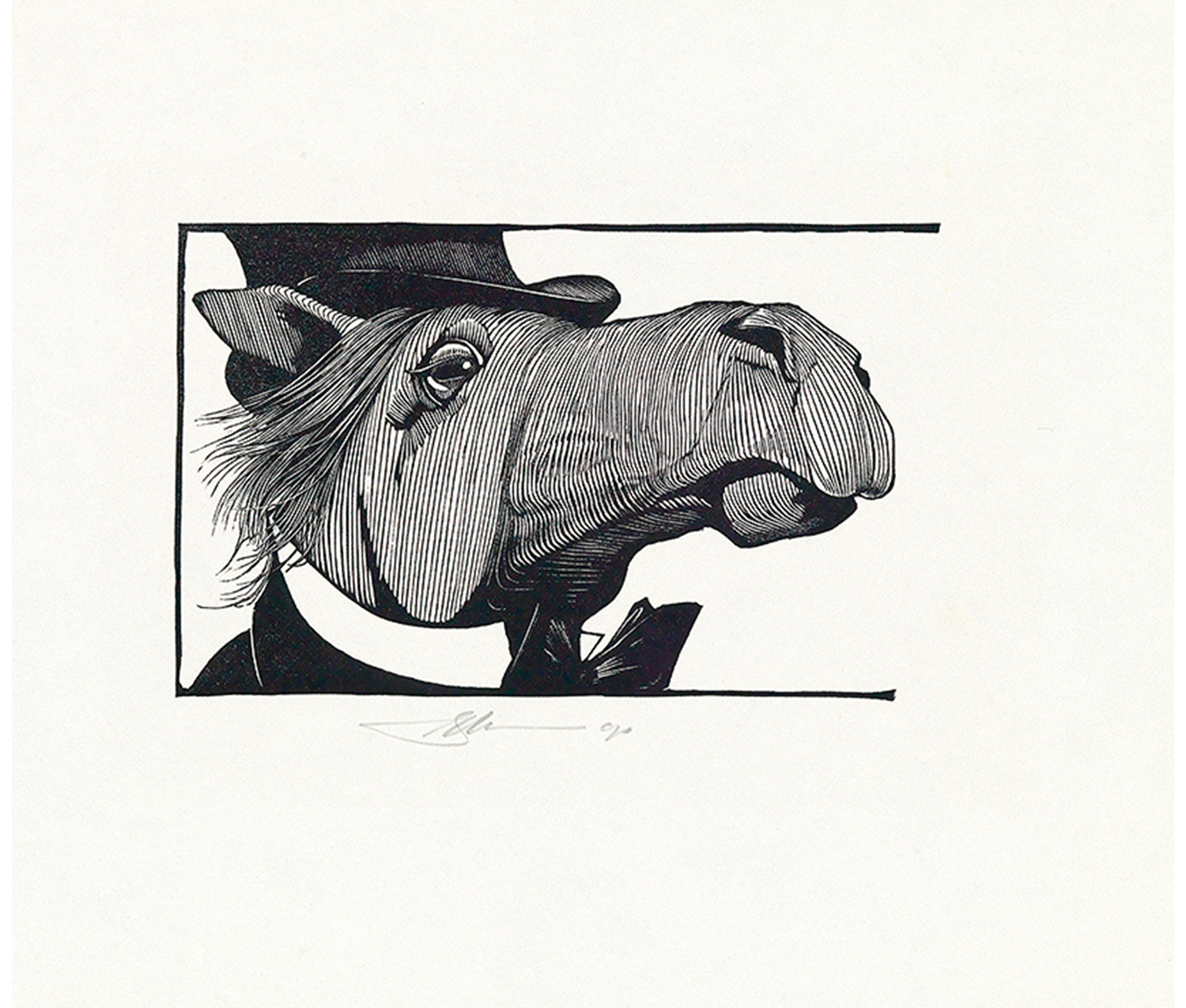

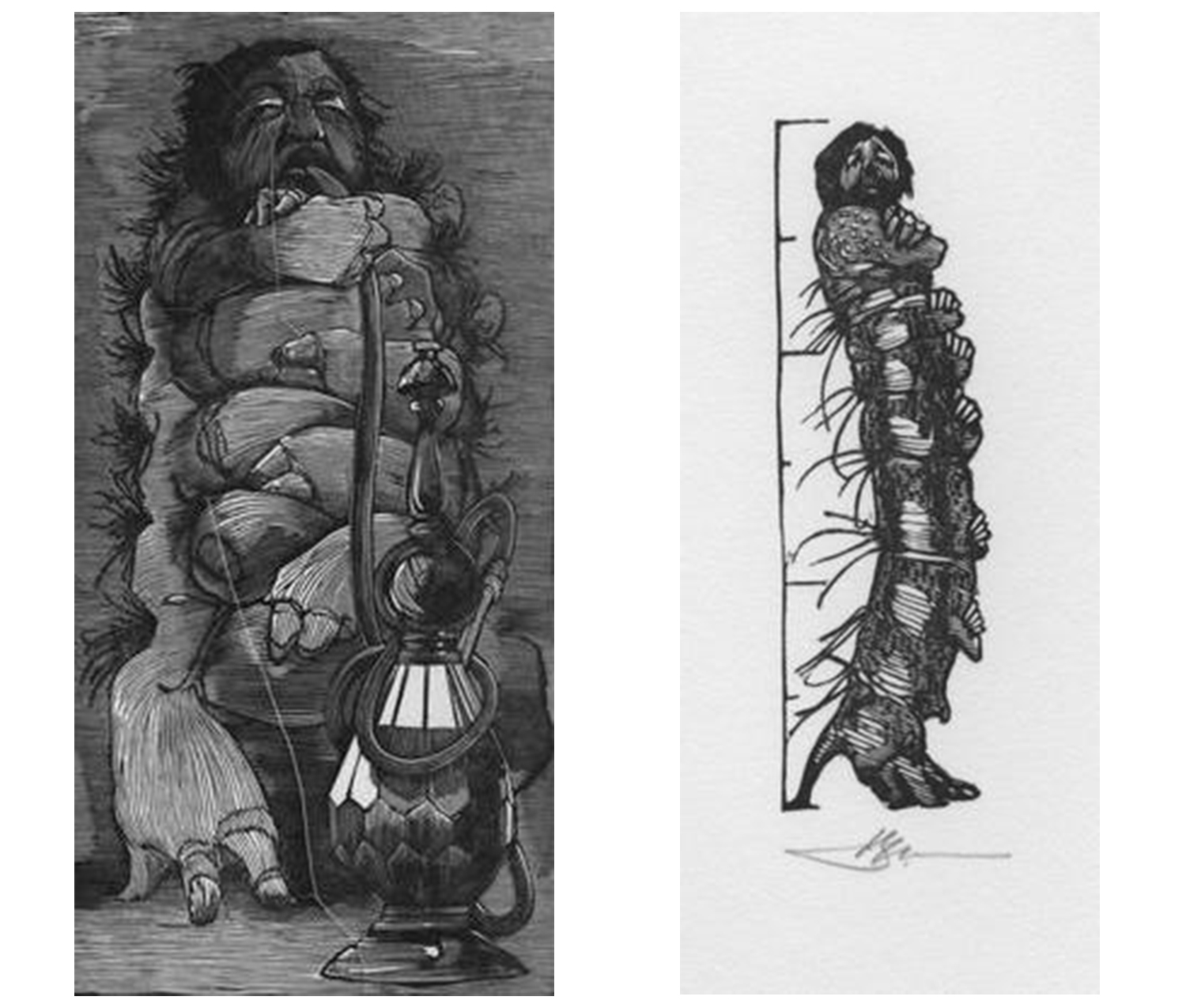

Although Moser looked up to Baskin, he soon developed his own style, saying “As I became comfortable with the fact of Baskin’s humanness . . . I began to think for myself and to form and respect my own opinions, independent of his--or anyone else’s.” This allowed him to develop in new directions for his Pennyroyal Press book projects such as Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There.

Barry Moser. American, born 1940. The Lady and the Merman: He Sailed Off on His Great Ship..., She Sat There, Still as a Rock..., Up From the Depths Came the Merman, from Fifty Woodengravings, 1977 print; 1978 published. Wood engraving on white wove Mohawk Superfine. Gift of William M. MacRae. SC 1981.23.3.

Barry Moser. American, born 1940. The Horse from Through the Looking Glass and what Alice found there, 1983. Wood engraving printed in black on medium weight, slightly textured, cream-colored paper. Gift of Elizabeth O'Grady and Jeffrey P. Dwyer. SC 2014.54.21.

Moser based his illustrations of the caterpillar in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland on Leonard Baskin, first depicting him as a large, imposing figure with arms crossed and then as a figure who, while stern, is only three inches tall. This could represent the way Moser’s relationship to Baskin had evolved: initially Moser viewed Baskin as a somewhat intimidating giant of the art world, but eventually he felt that they were on more equal footing.

The Caterpillar from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Images courtesy of Barry Moser.

Both Leonard Baskin and Barry Moser made representational art including illustrated books, and both incorporated religious and mythological themes into their work. Moser learned important lessons from Baskin, but he didn’t stay in the shadow of the older artist for long. Throughout their respective careers, both artists developed their own styles and strengths while maintaining an atmosphere of mutual respect.