Liz Chalfin on Spirituality, Creation, and Alternative Printmaking

Indigo Casais ‘23 is a STRIDE scholar working with curator Emma Chubb and an Art History and English double major at Smith. Indigo is the curator of a cabinet titled 'Fits of Passion': Visualizing Romanticism in the Contemporary, which pairs Romantic and contemporary artworks. The cabinet is currently on view on SCMA's third floor.

Printmaker Liz Chalfin is the founder of Zea Mays Printmaking in Florence, MA, a studio that provides artists with a safe place to work and conducts research in alternative printmaking methods. Chalfin’s print Vishnu Dreaming Vishnu is displayed in the Fits of Passion cabinet.

Romanticism was a wide-ranging artistic and literary movement that explored alternatives to reason. Romantic poets and artists drew inspiration from subjects such as the supernatural, spirituality, dreams, nature, and political revolution. In this interview from March 2020, Chalfin and I discuss how some of these themes appear in her prints. We also talk about the process of researching alternative printing techniques and the social inequalities of the contemporary printmaking world.

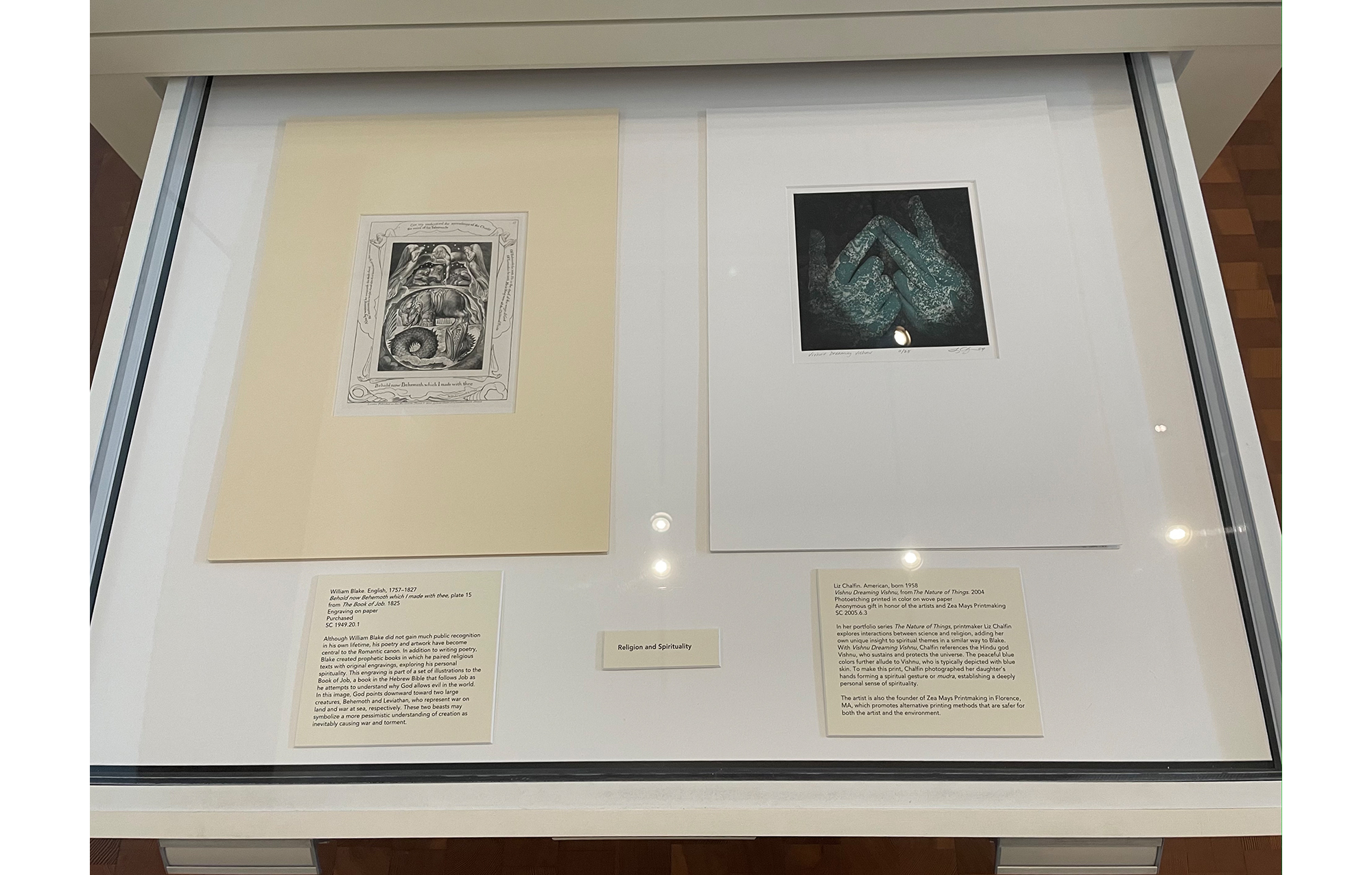

Could you speak to your motivations behind the print Vishnu Dreaming Vishnu, as well as the portfolio The Nature of Things, which the print is a part of?

I did a series of etchings that Vishnu Dreaming Vishnu came out of, and they all had to do with the intersection of religion and science. The Kansas State Board of Education was debating whether to include creationism as a part of the school curriculum, and it raised a lot of red flags for me that this was even being discussed as part of general education. It got me thinking about this intersection of how religion looks at ideas of creation and how science looks at ideas of creation.

I started to use material of religious sculpture and painting from different cultures over a long period of time, and one of them that I looked at was the Hindu sculptures of their gods that are involved with creation and destruction. The hand gesture in Vishnu Dreaming Vishnu is from one of these sculptures, but I had my daughter pose for me. All of the hands in this series are my daughter’s hands taking on the pose from a work of art from some point in history, from some culture that is dealing with these ideas of creation.

I was also looking at scientific ways of looking at creation, and so, superimposed on the hands is this microscopic imagery of plant life and sea life and things like that. Combining these two felt, to me, like a way to speak about the intersection of religious thoughts around creation and scientific thoughts around creation, and how there are areas where they overlap as well as distinct areas where they separate.

The Nature of Things is a portfolio that Zea Mays Printmaking published to showcase some of the art coming out of our studio in the early years. I invited a select group of artists to create an edition of prints on the theme “The Nature of Things,” intentionally open-ended. We have published two other portfolios since then, all with different themes.

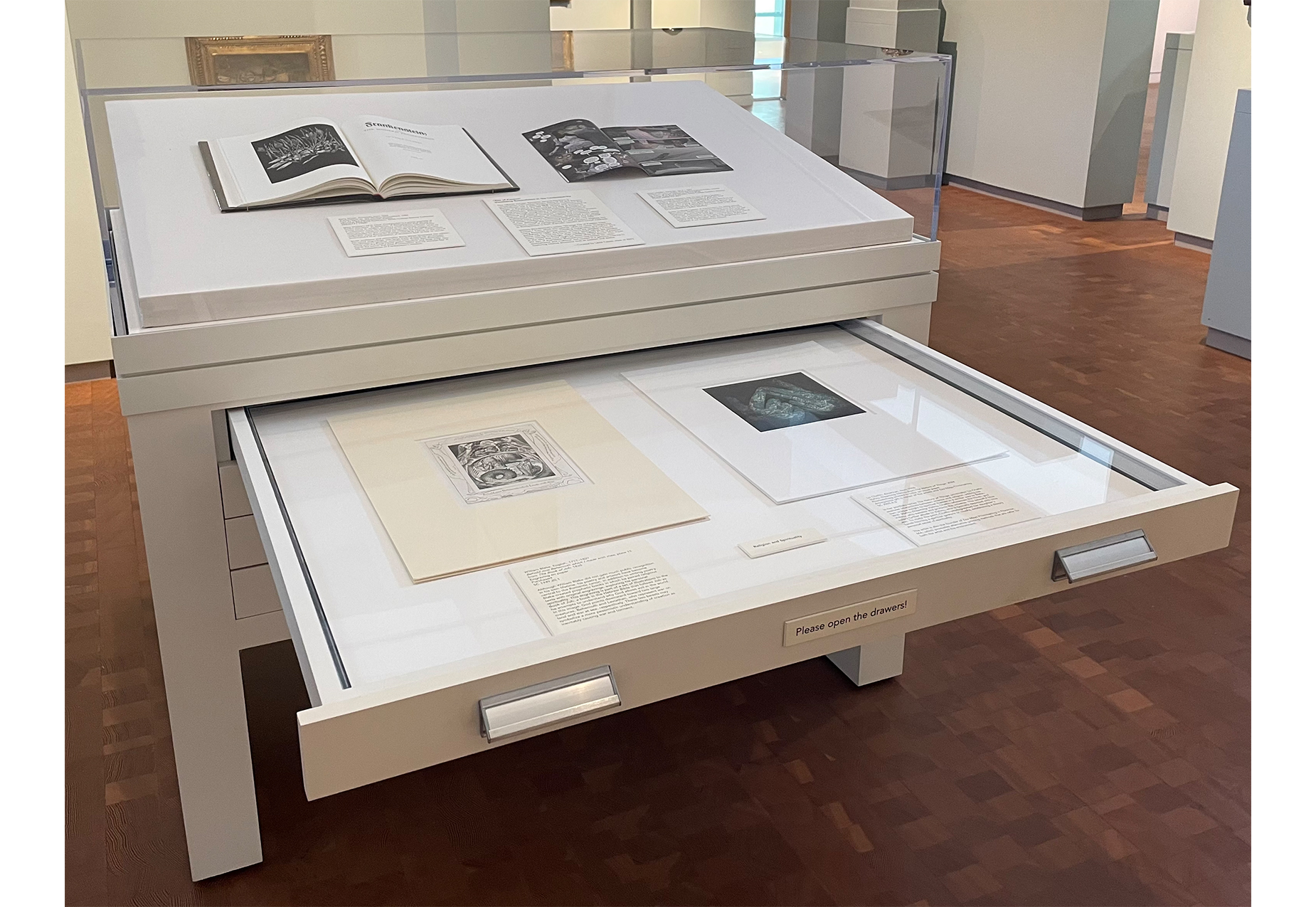

Vishnu Dreaming Vishnu (bottom right) displayed in the Fits of Passion cabinet.

Works shown:

Top left: Barry Moser. American, b. 1940. Frankenstein or, The Modern Prometheus, 1984. Text by Mary Wollstonecraft Shelly. Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College Special Collection. PR5397.F7 1984b.

Top right: Victor LaValle’s Destroyer, Issue 6, 2017. Written by Victor LaValle; illustrated by Dietrich Smith; colored by Joana Lafuente; lettered by Jim Campbell. Mortimer Rare Book Collection, Smith College Special Collection. PS3562.A8458 V52 2017.

Bottom left: William Blake. English, 1757–1827. Behold now Behemoth Which I Made with Thee, plate 15 from The Book of Job. 1825. Engraving on paper. Purchased. SC 1949.20.1.

Bottom right: Liz Chalfin. American, b. 1958. Vishnu Dreaming Vishnu from the portfolio The Nature of Things, 2004. Photoetching printed in color on wove paper. Anonymous gift in honor of the artists and Zea Mays Printmaking. SC 2005.6.3.

Do you frequently reference religion and spirituality in your work?

Religion and spirituality come into my work on occasion. I feel that religion deals with a lot of the giant issues that art deals with: what is the meaning of life, why are we here, how do we connect with the unseeable world, all those questions. They're often dealt with in a very dogmatic way in religion, and in a very open kind of way in art, but they are two paths seeking similar answers, in a way. Even though I’m not a very religious person, I do feel that religion has been one way that people explore the ineffable and the mysteries of life. And for me, I do it more through art, but I’m trying to work in the same terrain.

I’m interested in your work because it addresses the idea of creation, which you mentioned earlier. Romantic artists addressed this theme, but only in a very Christian context. Your piece adds multiple new dimensions to this topic. It addresses spirituality, as we discussed, but your printmaking techniques also show the physical creation process and document it very well. Could you speak more to the physical creation aspect of Vishnu Dreaming Vishnu?

These are etchings, and that’s one of the primary mediums I work in. What I like about that is, as you’re saying, I feel like etching really speaks to the documentation of creation because so much of the history of the process is apparent in the plate. [Vishnu Dreaming Vishnu] is a two-plate etching. It started out as a photo-etching of my daughter’s hand, which I then etched that image into copper and then worked on top of that with hand work, dry points, hard and soft ground, aquatint, and other printmaking techniques, to enhance the image. Similarly, the scan of the microbial information started as a photo-etching, but then was enhanced through my own handwork and reprocessing the plate. And then those were printed on top of each other, one plate first and then the second plate, with a transparent ink color overlay on one of the plates to bring out the color.

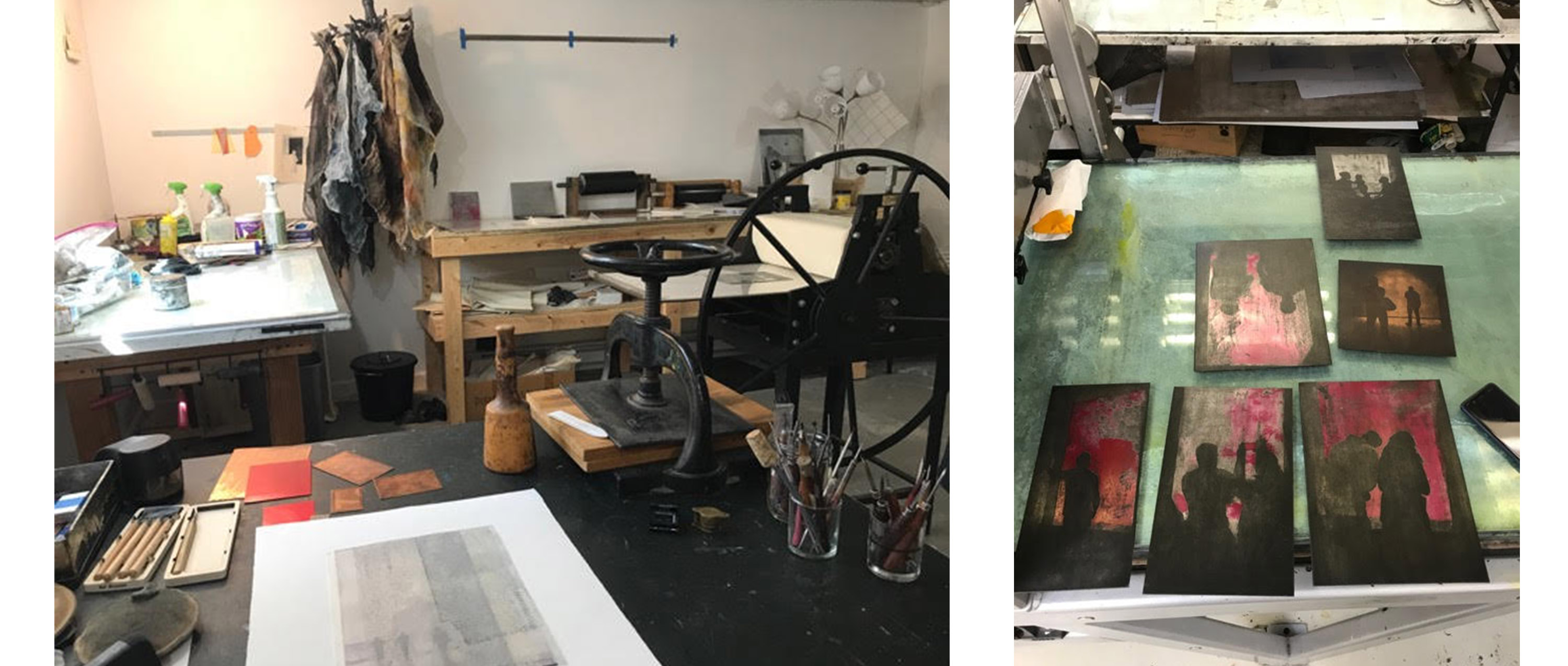

Left: Chalfin's home studio. Photo courtesy of artist.

Right: Etching plates in progress. Photo courtesy of artist.

Your work has been helpful in my studies, as well as many artists’ studies, in alternative and green printmaking techniques. How did you first get involved in green printmaking, and how do you think that the material sustainability of your work influences its content?

Well, I got into this over 25 years ago, actually. In the early 1990s, I was teaching at a college in California, Whittier College. They moved the print shop into a basement, with no windows, and wanted me to teach etching. And I was kind of horrified that we were going to create this really dangerous chemical soup and students would be working in this environment that I knew wasn’t healthy. At that time there were some artists and scientists working in Scotland and Canada who were starting to do research on this. I reached out to them and they were super generous in terms of sharing with me their formulas and recipes and ideas, and that’s kind of what sparked my interest in safer printmaking.

I switched over the shop at Whittier College to work with these safer materials, and it changed my whole thinking about teaching, printmaking, health and safety, and the environment. All of that came together at that time, and that’s when I started to conceive of the idea of opening up a studio that could be a research center to really research new techniques and alternatives, and also to provide a working space for artists to try all these things out, to create a space for artists who are not in academia. And so all of that kind of drove the founding of my print studio.

In terms of my own work, because we’re so research-based, we’re always trying out new techniques, new chemistry, new products that come on the market. My work has kind of followed along with that. As I’m experimenting with things, they get woven into my own work. It’s really hard for me to separate the research we do here from my own practice, because they really dovetail.

Vishnu Dreaming Vishnu (right) displayed next to William Blake's Behold now Behemoth Which I Made with Thee (left).

Romantic art and literature were very male-dominated. Are there any similar inequalities in the contemporary printmaking world that frustrate you?

Yes. It’s so interesting because I think most of the people who are practicing printmaking these days are women. And yet, most of the people in positions of power within printmaking are men. I feel like there is a gender imbalance, and a glass ceiling, in terms of who gets shown and who gets collected, that still hasn’t broken down. I feel, definitely, like there are class barriers for people. Even here at my own studio, because of the cost of equipment and maintaining materials, in order to survive as a business, we have to charge certain amounts for people to have access, which leaves out a lot of people. There’s a lot of class stratification within printmaking because of access to resources. And then there’s also who gets trained, who has access to courses and schools, what the public schools offer. That is completely based on class, race, and gender bias, I believe.