Look at Me, Me, Me! The Art of Narcissism

Henriette Kets de Vries is the Manager of the Cunningham Center for Prints, Drawings and Photographs and Assistant Curator of Prints, Drawings and Photographs at SCMA.

A recent New York Times article described the latest trend in diets. It was called “The Mirror Fast.” This diet was not prescribing the usual avoidance of certain foods or some exercise regime, but instead suggested a diet of one’s own mirror reflection. While the author of this new diet, who did not look at her own reflection for a year, recommended it mostly to women who might suffer from societally induced body image distortion, we might propose something along these lines as a more general solution for our society which has come to exhibit over the past couple decades an arguably unprecedented degree of self-obsessive disorders. Just the same, narcissism is not a new thing. Just read from Shakespeare or the classics and you come across many a picture perfect narcissist.

Pop artist Andy Warhol predicted in 1968 that a time would come when everyone would be famous for 15 minutes. Fast forward to 2013 and we find ourselves living in a culture where we advertise the most intimate details of our lives through tweets and Facebook while recording our selfies with our iPhone cameras―a brave new generation, hunched over, umbilically connected to our devices waiting for our “friends” to virtually “like” us.

Of course much has already been written on the rise of what seems to be an increasingly self-absorbed and exhibitionistic society that promotes and publicizes the “I” perhaps at the expense of the “We.”

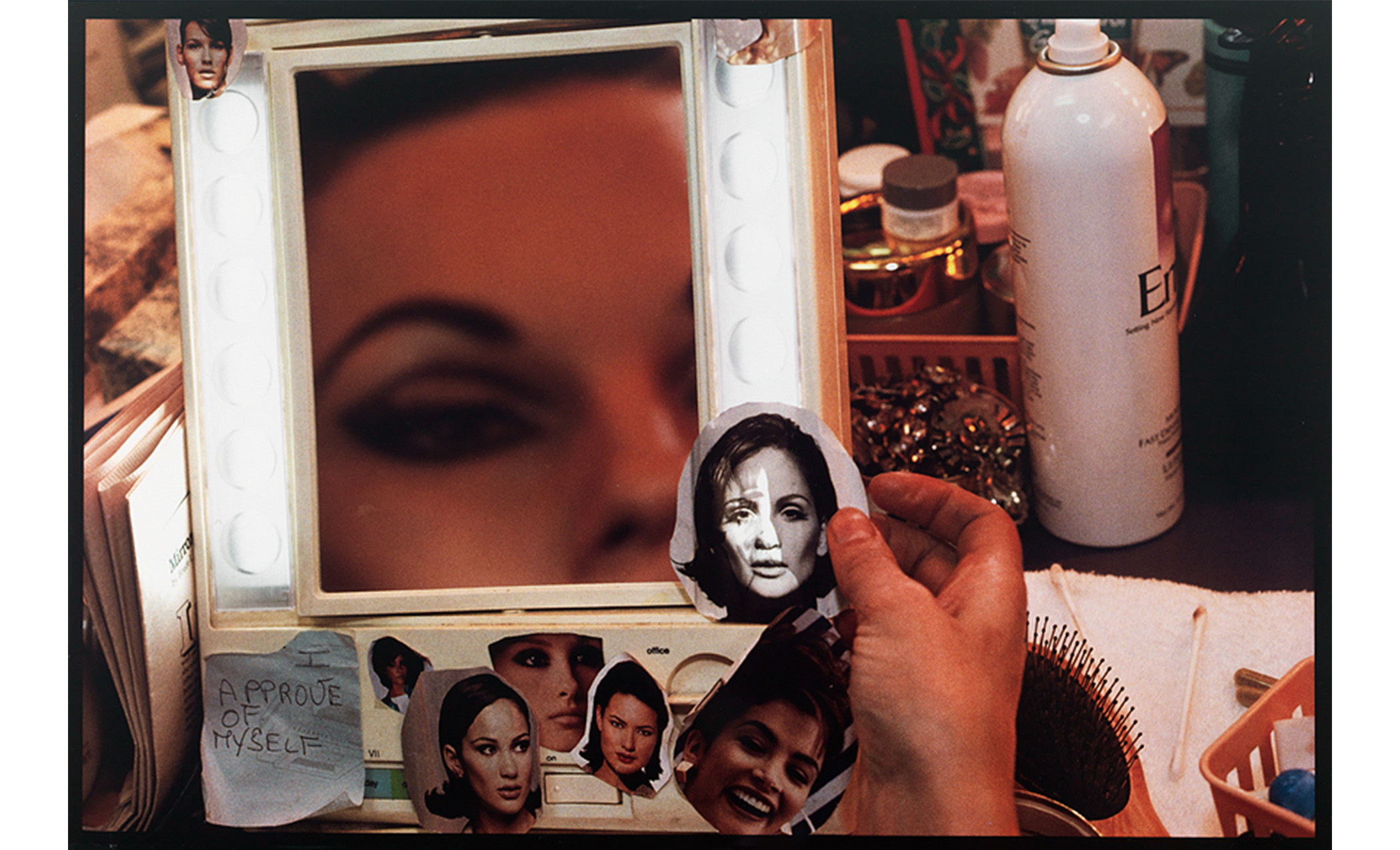

Lauren Greenfield. American, b. 1966. Showgirl Anne-Margaret in her dressing room at the Stardust Hotel, Las Vegas, Nevada. She tapes a note that says, "I approve of myself" and pictures of models she admires to her mirror for inspiration, from Girl Culture, 1998. Dye destruction print. Gift of Susan and Peter MacGill. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2011.72.25.

The emergence of these books and articles about the rise of narcissism could however also be a sign of a rising awareness urging for some societal recalibration. Historically humanity has reached similar realizations and often societal limits were created to reign in these excesses. In ancient Greece societal myths like the famous story of the youth Narcissus, who pined away after falling in love with his own reflection, warned of the detrimental consequences of such vices as self-love, vanity, and pride. In the early Middle Ages, basic moral edicts were cast as the cardinal (or Seven) deadly sins. While the early Christian theologians did not always agree on the number or order of mortal sins, Pride and (or Vainglory) was ultimately regarded as the worst: the origin of all evil, the one that started it all…

Government and church implemented sumptuary laws that have functioned over the ages as a sort of “fashion police,” restricting the type and number of luxury goods a person could buy or wear. Such laws were instituted by the Greeks, and after them the Romans, continuing on in various forms not only throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance, but even into to puritanical New England, where flashy lace collars were just not done.

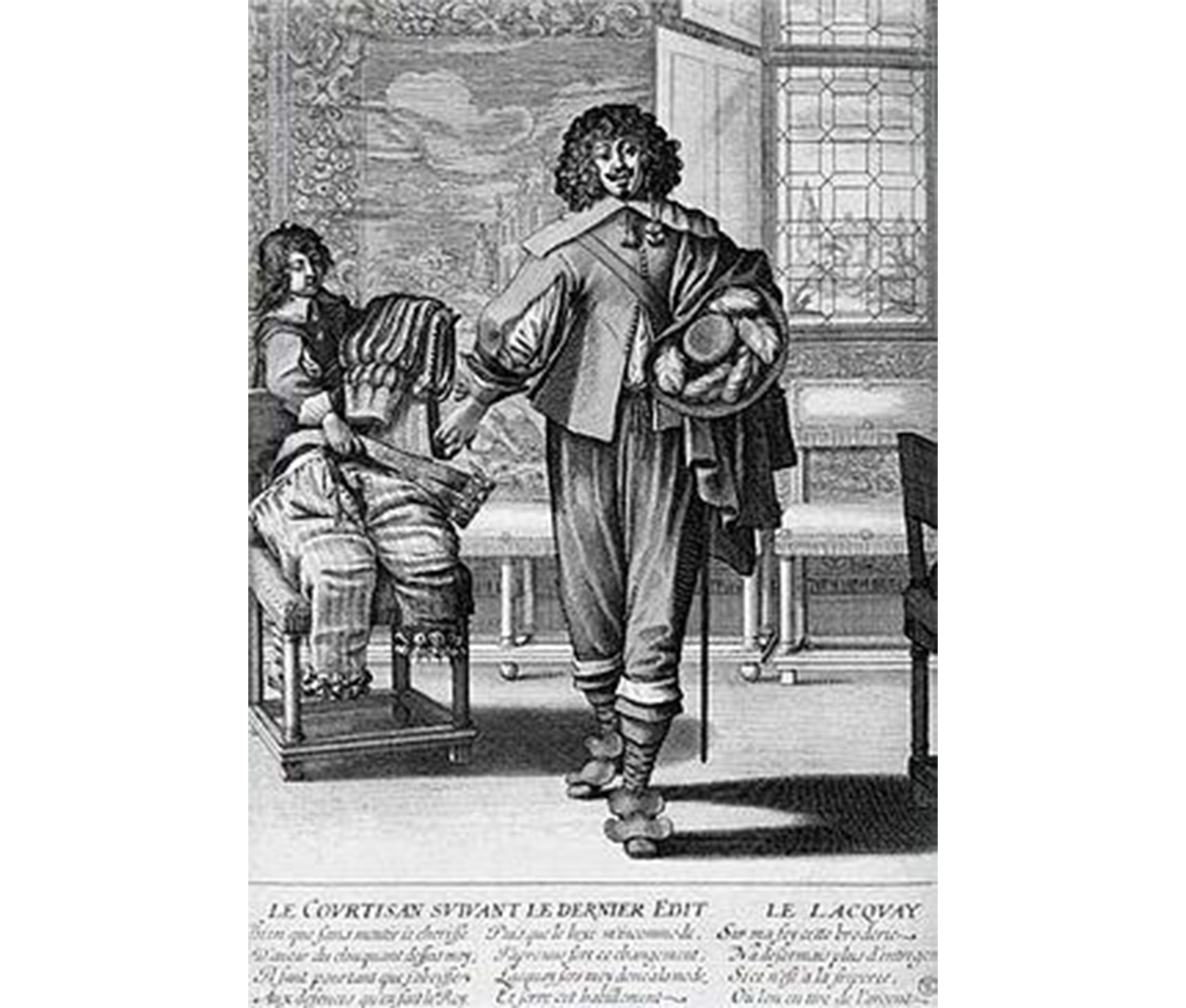

Abraham Bosse. French, 1602–1676). Le Courtisan suivant le dernier édit, ca. 1633. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 53.523 (print not part of the Smith College Museum of Art collection).

[above] Louis XIII (quite the dandy himself) imposed on the 6th of February 1620, laws that ordered the population to wear simpler clothes with less ornament. The courtier in this print is taking off his elaborate clothing and replaces it with simpler garb.

We feature a newly acquired series of wonderful moralizing prints in our collection that addresses this concern with the subject aptly titled: The cycle of the Vicissitudes of human life. These prints were rendered as a warning to the good and wealthy Flemish folk of the 16th century, demonstrating in strong symbolic visual language that one phase of the human condition could lead to the next. It all starts with Lady Prosperity whose actions lead to Pride, who births the child Envy with its snakes for hair, which in turn will lead to War, who will give birth to Poverty dressed in rags, which will lead to Humility, out of which will come Peace and finally go back to Prosperity which will deliver etc…..

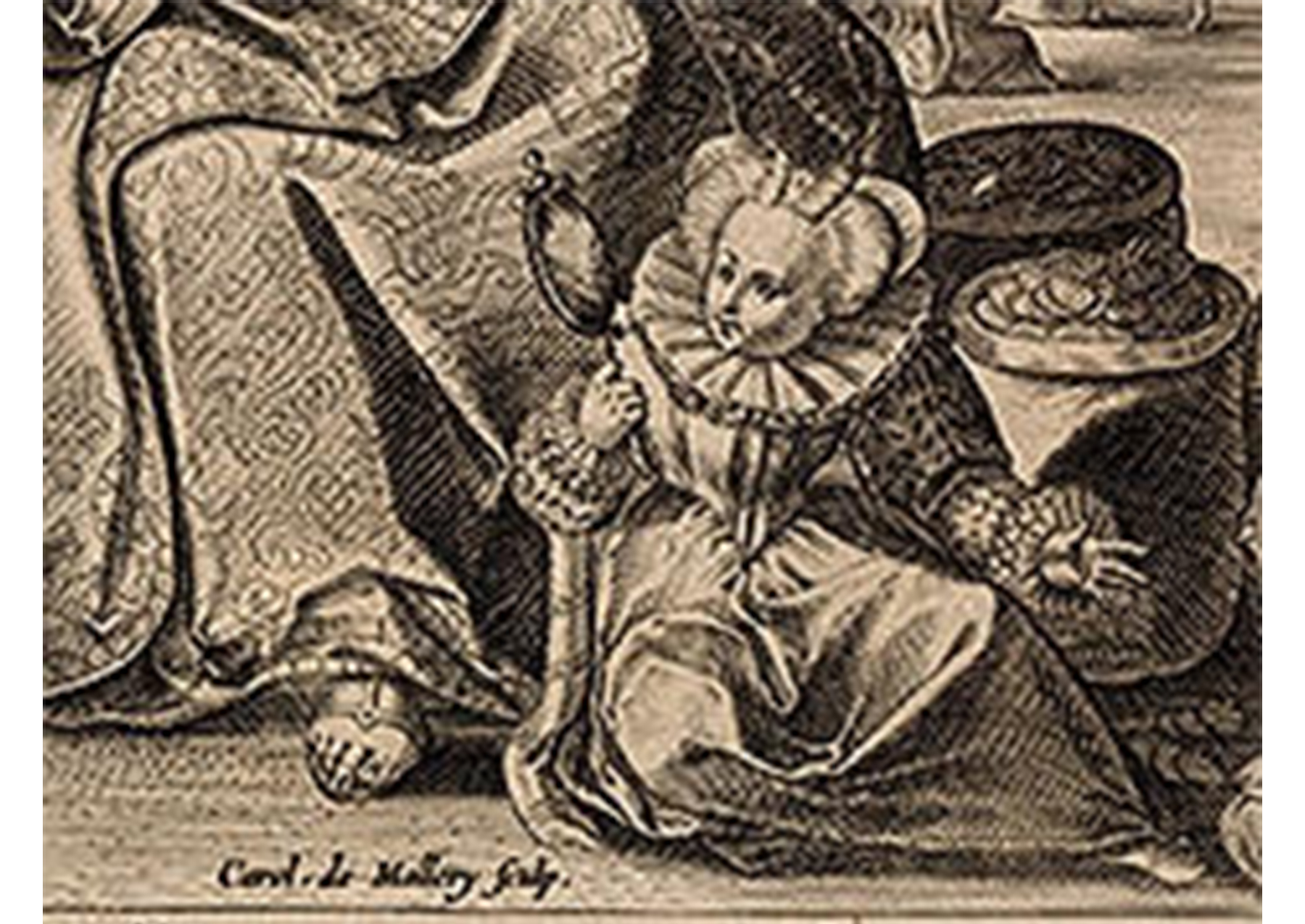

Karel van Mallery. Flemish, 1571–1635. After Maarten de Vos. Flemish, 1532–1603. Wealth Brings Forth Pride from The Cycle of the Vicissitudes of Human Life, 1581–1635. Engraving printed in black on paper. Purchased with the gift of Catherine Blanton Freedberg, class of 1964, in honor of Suzannah Fabing, Director of the Smith College Museum of Art, 1991-2005. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2013.40.2.

Detail of baby Pride from Wealth Brings Forth Pride, looking in her mirror

The prints were based on another series of prints by the well-known Haarlem artist Maarten van Heemskerck who drew his inspiration from a religious procession celebrating the Feast of the Circumcision in Antwerp in 1561.

Print 4 by Cornelis Cort (1533-1578) after Maarten van Heemskerk. Dutch, 1498–1574. The Cycle of Human Vicissitudes, 1564. Depicted is Pride holding her mirror. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 49.95.2371(3). (not part of Smith College Museum of Art collection).

While it may be hard to imagine such a colorful parade with its elaborate didactic scenes processing through the streets of present day Antwerp, it does say something about the popular awareness of such complex concerns.

During the Middle Ages the creation of art in the West had been more a communal undertaking. Artists were for the most part born into the profession. Art in those days was funded by the church or the nobility. Individualized and secular art was rare and these medieval artists were, as a rule, not appreciated for the originality of their work, but rather for its excellence in craftsmanship and technical skill. This all changed in the late Renaissance with the resurgence of individualism and humanism and the concomitant changes in the status of the artist. This was a time when self-portraits and aggrandizing portraits of the “average” person became quite popular. Artists also started to sign their name to their work and some even “hid” images of themselves in their own compositions.

Hendrik Goltzius. Dutch, 1558–1617. Circumcision, 1594. Engraving (detail). Metropolitan Museum of Art, 17.37.36. (print not part of the Smith College Museum of Art collection).

However in Northern Europe no self-respecting portrait was complete without some reminder of things to come. This often came in the form of a skull or an hourglass or putti blowing bubbles or a flower losing a petal or two; all symbols of the fragility of life and the vulnerability of times of prosperity. These visual reminders of death were placed as evidence of the sitter’s modesty and morality.

Jacob Matham. Dutch, 1571–1631. After Paul Morelsen. Portrait of the artist Abraham Bloemaert, 1610. Engraving on paper. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Ralph Rose (Clarice Goldstein, class of 1927). Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1973.9.6.

Detail from Portrait of the artist Abraham Bloemaert

Hendrik Goltzius. Dutch, 1558–1617. Quis Evadet?, ca. 1594. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 51.501.4929. (Not part of the Smith College Museum of Art collection)

While it’s clear that narcissism is not a new phenomenon, what does seem to be new is the status it has gained in our western society; narcissism has become our new religion. We now carry our narcissism with pride. While we imagine ourselves a society of individuals, social media suggests a miscarried longing for a lost communal spirit. We clearly still need acknowledgement from others, yet we find ourselves stuck staring at our own reflection in the mirror.

Francisco José de Goya y Lucientes. Spanish, 1746–1828. Hasta la muerte. (Till Death), Plate 55 from Los Caprichos, 1799. Etching and aquatint printed in black on laid paper. Purchased with the gift of Albert H. Gordon. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1964.34.55.

I guess what history and art teaches us is that we all could use a symbolic hourglass or two on our bedside table or an occasional mirror fast. It won’t change our longing for feeling special but might make for a better and maybe healthier worldview.