Luxury Objects in the Age of Marie Antoinette: Lace and Porcelain

The Smith College Museum of Art is dedicated to bringing out works on paper into the main galleries, where all visitors can see them. Since works on paper are more sensitive to light than other mediums, SCMA has installed special Works on Paper cabinets throughout the galleries for the display of prints, drawings and photographs. Today’s post is part of a series about the current installations of the Works on Paper cabinets, which will remain on view through August 2016.

Guest bloggers Madison Agresti ‘19 and Emma Ning ‘19 are Smith College students and two of the authors of this cabinet. This installation derives from a First Year Seminar in Fall 2015, Re-Membering Marie Antoinette, taught by Professor Janie Vanpée. In this seminar the students collaborated to create an online exhibition that examined the economic, social, and aesthetic roles of an array of luxury objects and cultural practices in the late eighteenth century.

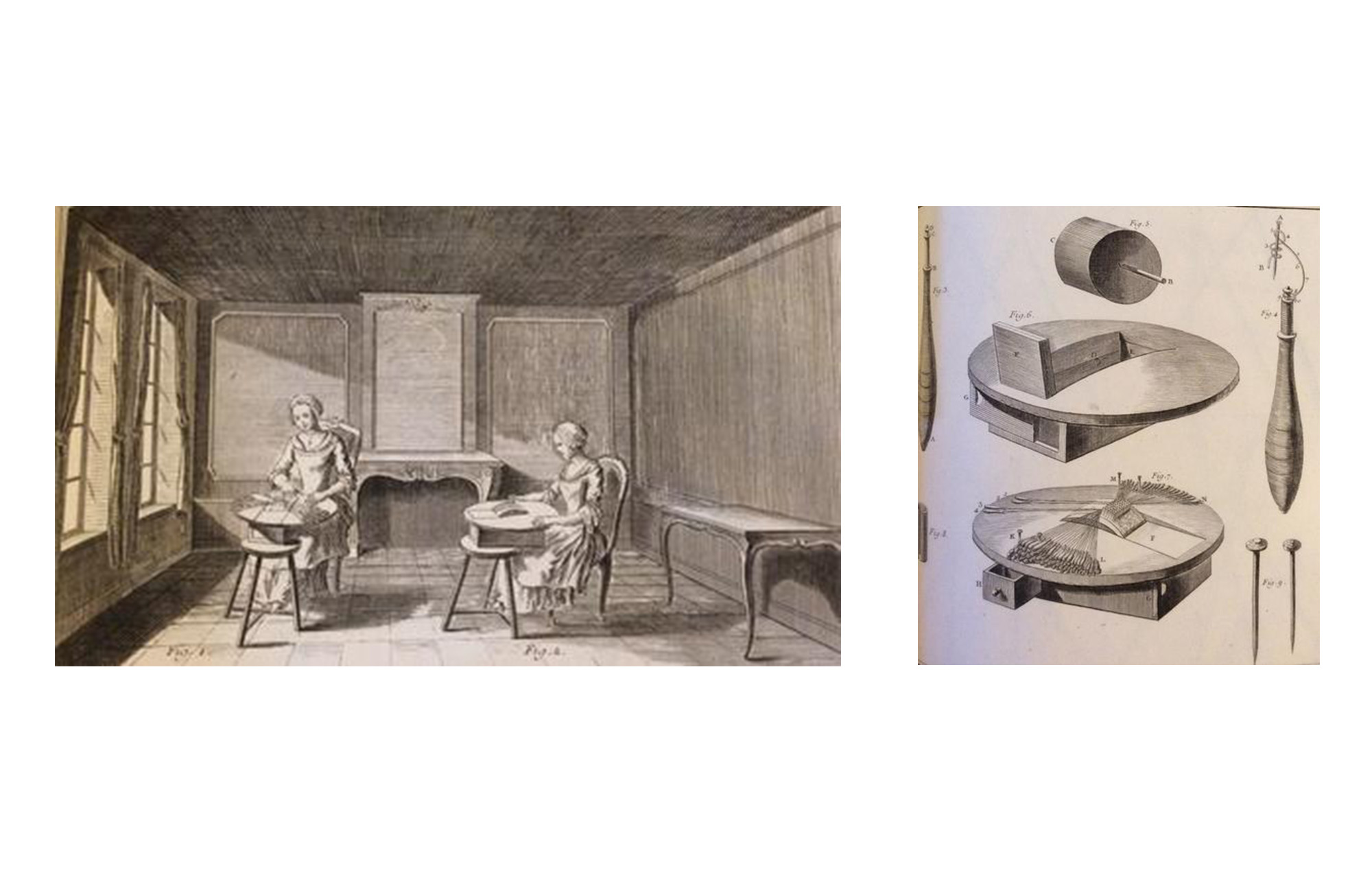

During the eighteenth century lace adorned almost every ensemble worn by the French aristocracy and the wealthy bourgeoisie. Lace originated in Italy and Flanders in the early sixteenth century, but Colbert, Louis XIV’s finance minister, began to promote it as a French industry to rival that of Venice in the latter half of the sixteenth century. The first cradle of lacemaking in France was Alençon, celebrated for its own particular pattern, the point de France. As plates from Diderot’s Encyclopédie illustrate, lace makers, or dentellières, were mostly women who typically worked at home, sometimes going blind from spending so much time turning thread into intricate designs.

From Diderot's Encyclopédie. Paris, 1782–1832. Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College.

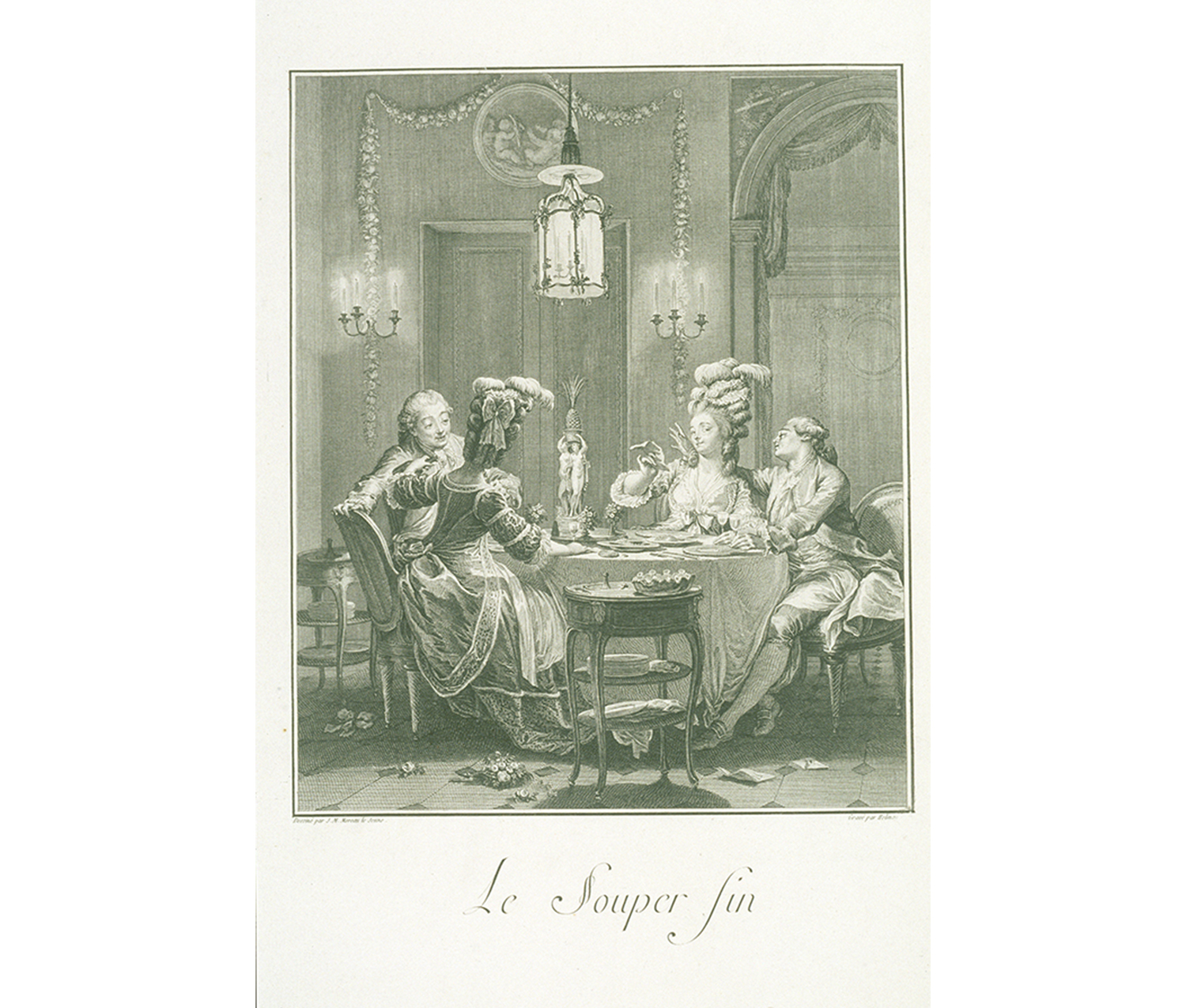

Porcelain also had many uses in eighteenth-century France, from decorative sculptural pieces to more utilitarian cosmetic pots, vases, inkstands, and tableware like wine coolers, tureens, and tiered table centerpieces, as the scene of two couples flirting over a late supper in Moreau le Jeune’s Le Souper fin illustrates well.

Jean-Michel Moreau le Jeune. French, 1741–1814. Le Souper fin, from Monument du costume physique et moral de la fin du dix-huitième siècle ou tableaux de la vie, 1789. Engraving on paper. Purchased with the gift of Mrs. Charles Lincoln Taylor (Margaret Rand Goldthwait, class of 1921). SC 1964.24.24.

The extensive gilding and range of enamel colors on this porcelain cup and plate are typical of the decorative style developed by the Sèvres Porcelain Royal Manufactury after the discovery in the 1760s of the once-secret ingredient, kaolin, used in China to make high-fire, hard-paste porcelain. Unlike the porcelain plates and decorative centerpiece featured in the print, Le Souper fin whose style dates from the late eighteenth-century, this cup and plate reflect the Neoclassical style fashionable under Louis Philippe.

Sevres Porcelain Royal Manufactory. French, established c. 1750. Cup and Saucer, 1846. Porcelain. Gift of Harriet D. Carter, AB class of 1931, MLA class of 1935. SC 1979.36.1ab.