Maximón Militar

Karla Giorgio AC ’13J is an Art History and Latin American Studies double major at Smith.

Guatemalan saints, beatos (blessed people) and deities usually represent holiness, innocence and purity of heart, yet the enigmatic Maximón, with his taste for alcohol and tobacco, is an unorthodox figure among Guatemalan congregations. Despite his unsavory character, Guatemalans’ worship of Maximón increased after 1880, especially in the highlands.

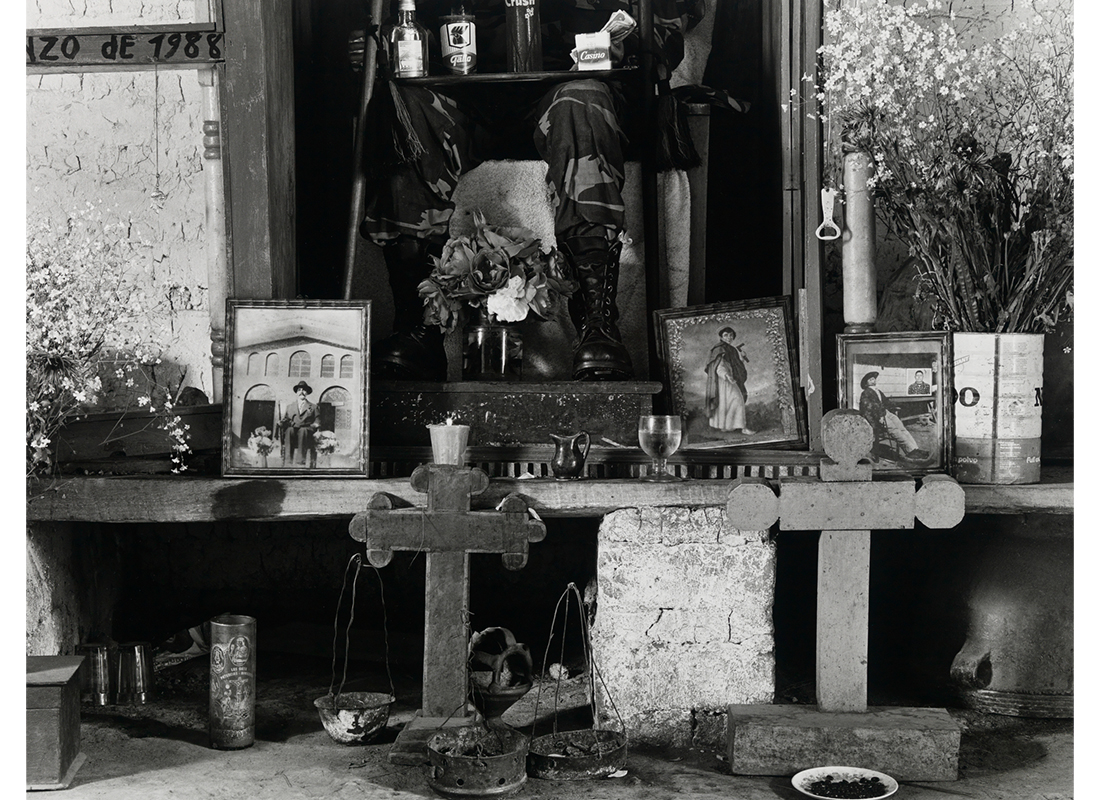

This folk saint has been venerated in a range of forms and dressed in different costumes for public rituals, especially during Holy Week, by Ladinos (people with indigenous and Spanish heritage) and indigenous people. In Chauche’s photograph, however, Maximón is wearing a military uniform and newly polished combat boots. He is holding an elongated object which appears to be a rifle and a rustic tray, which contains his favorite offerings: agua ardiente (alcohol), soda and cigarettes. Chauche only reveals the lower half of Maximón’s body. It is here where Maximón Militar – a deity, a doll, a figure, a religious hybrid – not only embraces two different religious worlds, the Maya and the Spanish, but goes a step further into a new ritual, war.

Daniel Chauche, while avoiding capturing the face of Maximón, finds a way to depict the shame and fear of the Guatemalan people and perhaps, as long term resident, his own, as well as the consequences of a long civil war that plagued the country.

Guatemala, like the majority of the countries in Latin America, gained its independence from Spain in the 1820s yet, at least for the Guatemalans, independence from European tyranny did not assure economic prosperity or peace among its people. Moreover, after independence, Guatemala had been a victim of authoritarian governments, harmful foreign interventions, and an unprecedented military coup in 1954. The coup not only established the modus operandi of foreign and domestic policy aimed at any political party that sympathized with communist or socialist ideals, but it also destabilized the country and unleashed one of the bloodiest civil wars in Latin America lasting nearly forty years.

Daniel Chauche took Maximón Militar in 1989 during the civil war in Guatemala, seven years before the peace accord between the government and rebel groups was signed. The sense of shame and fear is clear, however, questions still are unanswered. What was the real reason why Chauche omitted the upper body of Maximón? Or is perhaps the man/figure wearing the military uniform and the shiny boots not Maximón at all but is instead a member of the military force and the Maximón is depicted only by the two pictures of San Simón/Maximón placed at the feet of the military figure?