Monsters

Henriette Kets de Vries is the Manager of the Cunningham Center for Prints, Drawings and Photographs and Assistant Curator of Prints, Drawings and Photographs at SCMA.

My nine-year-old daughter loves Halloween. She loves the thrill of being frightened under safe conditions and, of course, the free candy. Walking past ghouls and monsters, she pinches my hand in gleeful but nervous anticipation. She is not the only one; the love of the uncanny and creepy is innate and a way of dealing with the darker side of life for many of us. Fellow Halloween-lovers can see the creatures that live within the SCMA vaults in the current Cunningham Corridor installation Monsters.

I’m personally not a big fan of horror movies, but I love a good ghost story. We all have a relationship to the monsters we create in our subconscious or the ones we find in newspaper headlines. The obsession with modern day monsters, like serial killers, has only grown and has even made it to the mainstream, as TV shows like Dexter demonstrate. Monsters have always been part of us. They are familiar and the ‘other’ at the same time. Throughout history and across all cultures monsters have found their place. They frequent our dreams and nightmares, and surface in our stories and visual arts. In ancient Greek myths, many fantastical beings were brought to life to embody the darker, internal struggles of the hero while infusing the tale with complexity and wonder.

Elliot Offner. American, 1931–2010. Griffin, 1974. Woodcut printed in color on deckle edge paper. Bequest of Phyllis Williams Lehmann. Photograph by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 2005.11.39.

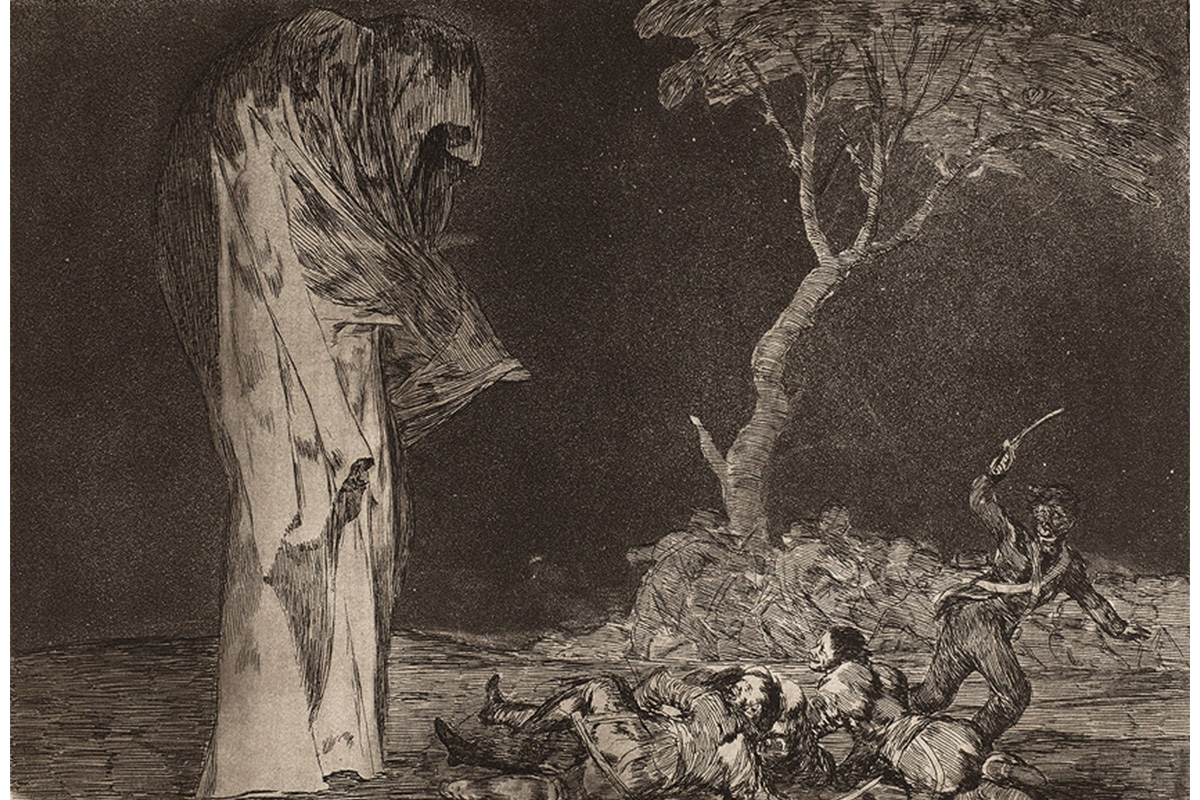

Early Christianity, with its apocalyptic worldview, introduced a new visual vocabulary of monstrosities. In the course of their devout labors, monastic scribes would be ‘visited’ by grotesque and ribald creatures who were then inserted into the margins of their illuminated manuscripts. While some of these monsters appear to be light-hearted or trivial marginalia, other manifestations came to be directly equated with Satan, Hell, and the seven deadly sins. Meanwhile, in everyday life, disfiguring diseases and birth defects were taken as evidence of the sufferers’ depravity, making them seem like monsters themselves.

Non-western art was just as replete with monstrosities. Whether in early Japanese woodblock prints, Persian Mughal court painting, Inuit or African art, artists illustrated their own myths and folktales with colorful and complex demons and monsters.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi. Japanese, 1798–1861. Kuwana, Station 43, from the series Fifty-three Pairs of the Tokaido, n.d. Woodcut printed in color on paper. Purchased with the Winthrop Hillyer Fund. Photograph by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1915.10.25.

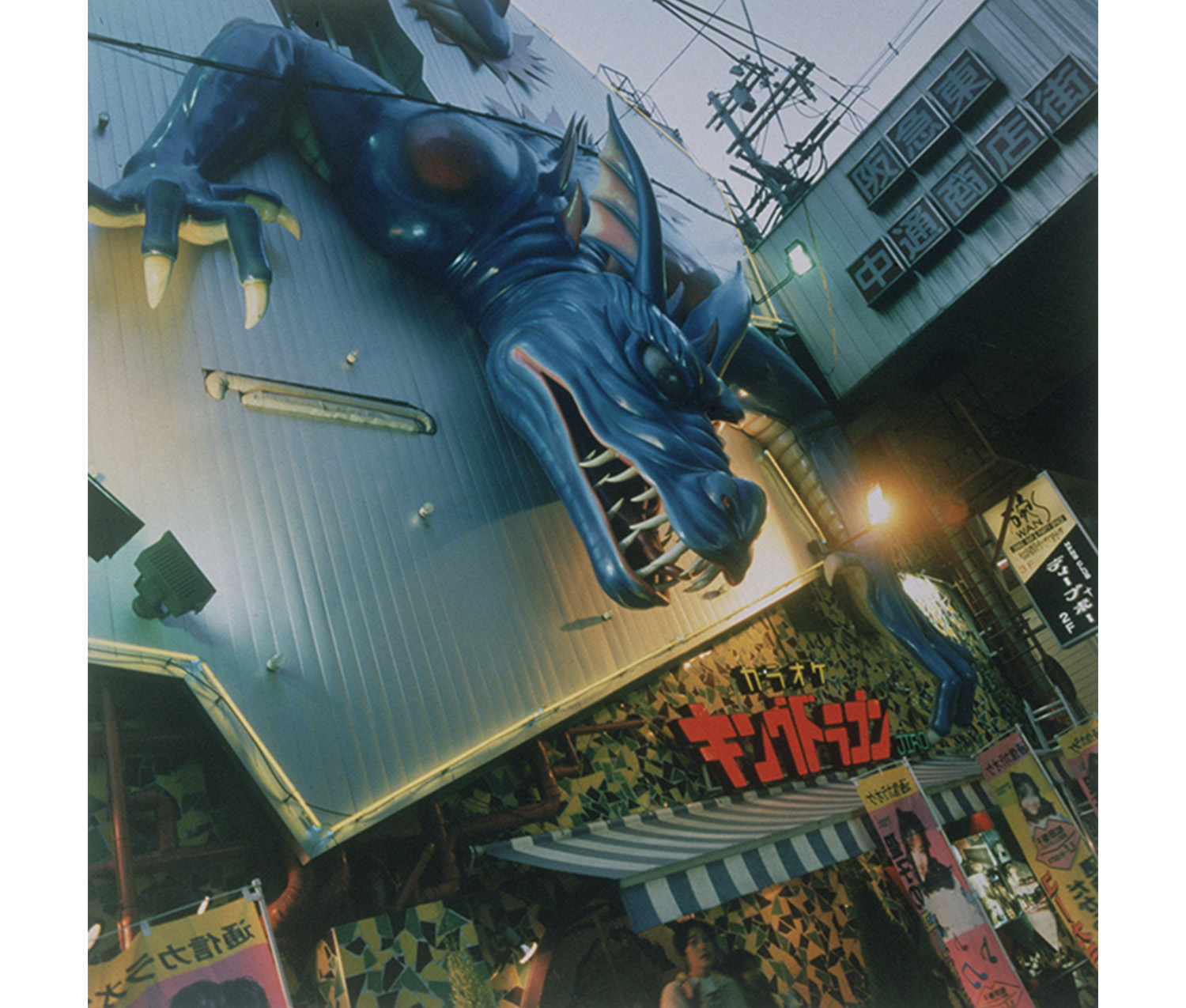

The Japanese horror and anime genre has grown significantly in popularity in the West over the last twenty years. Originally an oral tradition, pre-air-conditioning Japan loved the ‘cold chills’ that came with the telling of horror or ghost stories on hot summer nights. Its roots can be found in ancient Japanese folklore which gave birth to innumerable yokai and or mononoke (strange apparitions, i.e., monsters) rivaling our western fascination with monsters.

In contrast with the interpretation of monsters in the West, which relies heavily on the Christian doctrine of Good versus Evil, the Japanese yokai have a deep connection to nature and depend on the Taoist principles of Yin-Yang (“shadow and light”). Japanese monsters are fluid and can fluctuate between being interpreted as good, bad, funny, or evil, or sometimes all of the above. They are there to remind us of the transmutability of all things uncertain and boundless. Yokai represent the imperceptible things that surround us that are given form by the boundless fears, anxieties, and contradictions in our lives.

Unknown. Japanese. Man in the Grip of a Beast, n.d. Black ink with green, yellow, gray and rose watercolor on paper. Purchased with the Winthrop Hillyer Fund. Photograph by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1938.12.19.

Chester J. Michalik. American, born 1935. Osaka Japan, 1996. C-print. Purchased. Photograph by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1998.21.2.

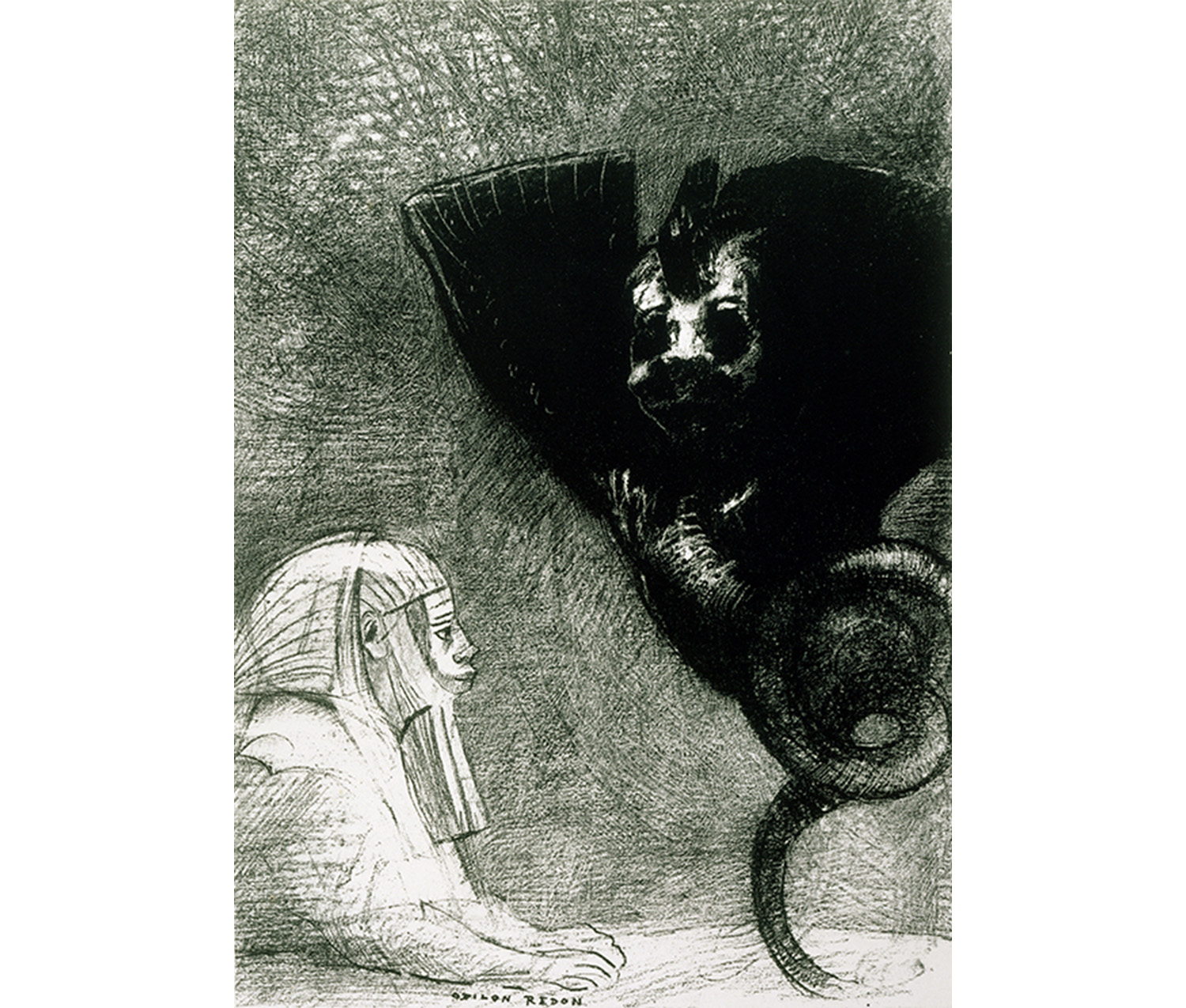

Today’s more secularized monsters, such as those terrorizing audiences of Japanese anime or Hollywood horror films, retain much of their former potency. The descent into the dark underbelly of human consciousness is still not a happy journey. Our fascination with monsters has hardly waned, and artists continue to invent wonderful new abominations that both fascinate and repulse us.

Monsters is on view on the second floor of the Smith College Museum of Art until February 3, 2013.

Odilon Redon; printed by Just Becquet. French, Redon 1840–1916, Becquet 1829–1907. Le Sphinx: ... mon regard, que rien ne peut dévier...,from Gustave Flaubert - La Tentation de St. Antoine, ca. 1889. Lithograph printed in black on chine appliqué on heavy white wove paper. Gift of Mrs. Bertram Gabriel Jr. (Helen Cohen, class of 1948) in memory of her parents, Sadie and Sidney S. Cohen. Photograph by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1989.21.3.