New York's Most Famous Unknown Artist

Kate Dempsey Martineau '04 was an OCIP Intern in the Cunningham Center during her senior year at Smith. She has since earned her doctorate in art history from the University of Texas in Austin and taught at both Keene State College and the University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Her book Selective Inheritance: Ray Johnson in Correspondence with and Beyond Marcel Duchamp is forthcoming from the University of California Press.

Two collages by “New York’s most famous unknown artist,” Ray Johnson, have recently arrived at SCMA as part of a promised gift. These are the first works by Johnson in the Five Colleges.

Johnson is known for his work in two media: collage and the mail. A prolific letter writer and illustrator, Johnson’s postal project grew dramatically over the years to become the New York Correspondence School. Ed Plunkett, a friend of Johnson’s, gave the group this title in reference to the New York School (another name for the Abstract Expressionists) as well as the popular classes one could take through the mail. Johnson dictated who could be a part of the school by sending out mailings to his chosen participants. After 1958 Johnson’s mailings often included the instructions “Please Send To [a specific person]” so that the first recipient served as a middleman. At times Johnson encouraged the first person to add to the contents before forwarding them, thus confusing the idea of authorship.

Johnson began working in collage around 1952. His early works tend to be spare emphasizing his strong sense of formal composition—he studied with Josef Albers, after all. He also served as an assistant for Ad Reinhardt in the early 1950s, whose work at this time was equally minimalist.

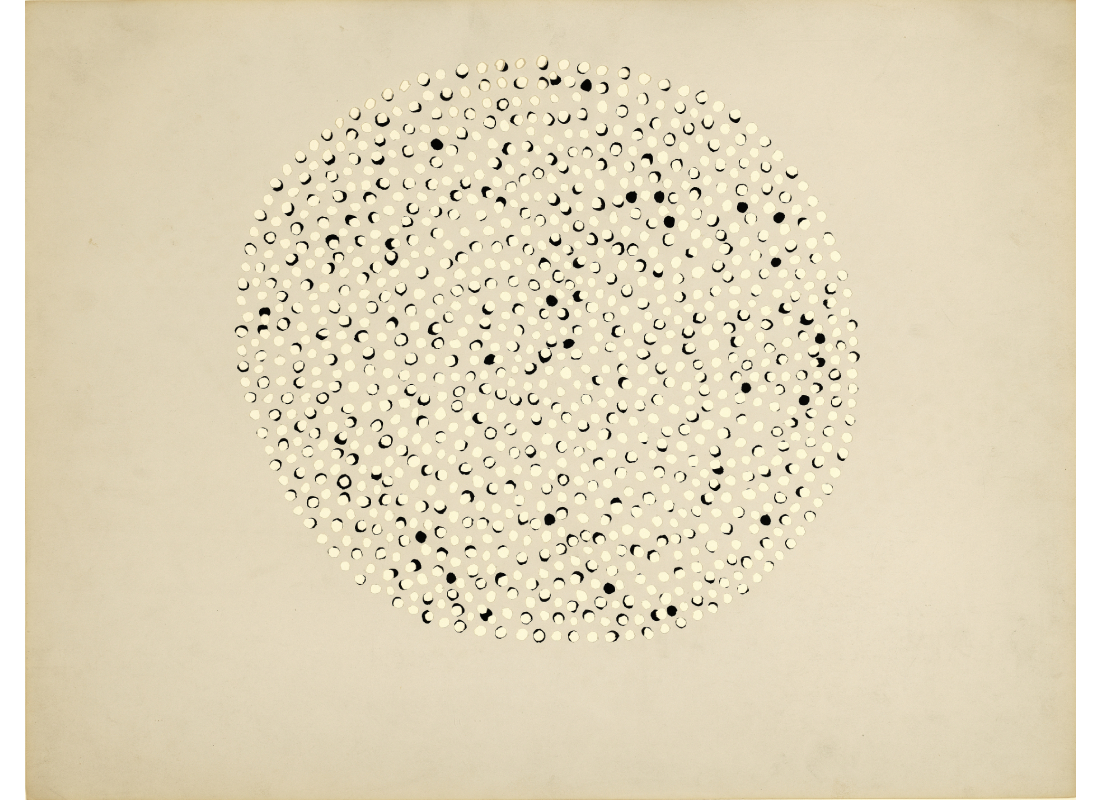

The first collage promised to SCMA is untitled and dates from the early 1950s and is very different than the work for which Johnson is best known. One could argue that this work is not actually a collage, for it does not appear to have involved any pasting (the usual criteria for the medium). Rather it consists of hand cut circles selectively emphasized with black ink. At first glance (or particularly in reproduction) one might assume that the white circles were added with paint just like the black or even that the black is what was cut away. The holes’ slight irregularity, their arrangement that never conforms to a perfect spiral, and the seemingly random highlighting with ink cause the work to visually pulsate or even spin in a counter clockwise direction. Although all of the white circles remain round (if slightly irregular), the range of shapes created with the black ink call to mind the phases of the moon and therefore contribute to the idea of orbiting. Later on Johnson would work in the negative in an analogous way, creating star-like specs of white amid dark sections of his collages by meticulously inking around small areas of blank page.

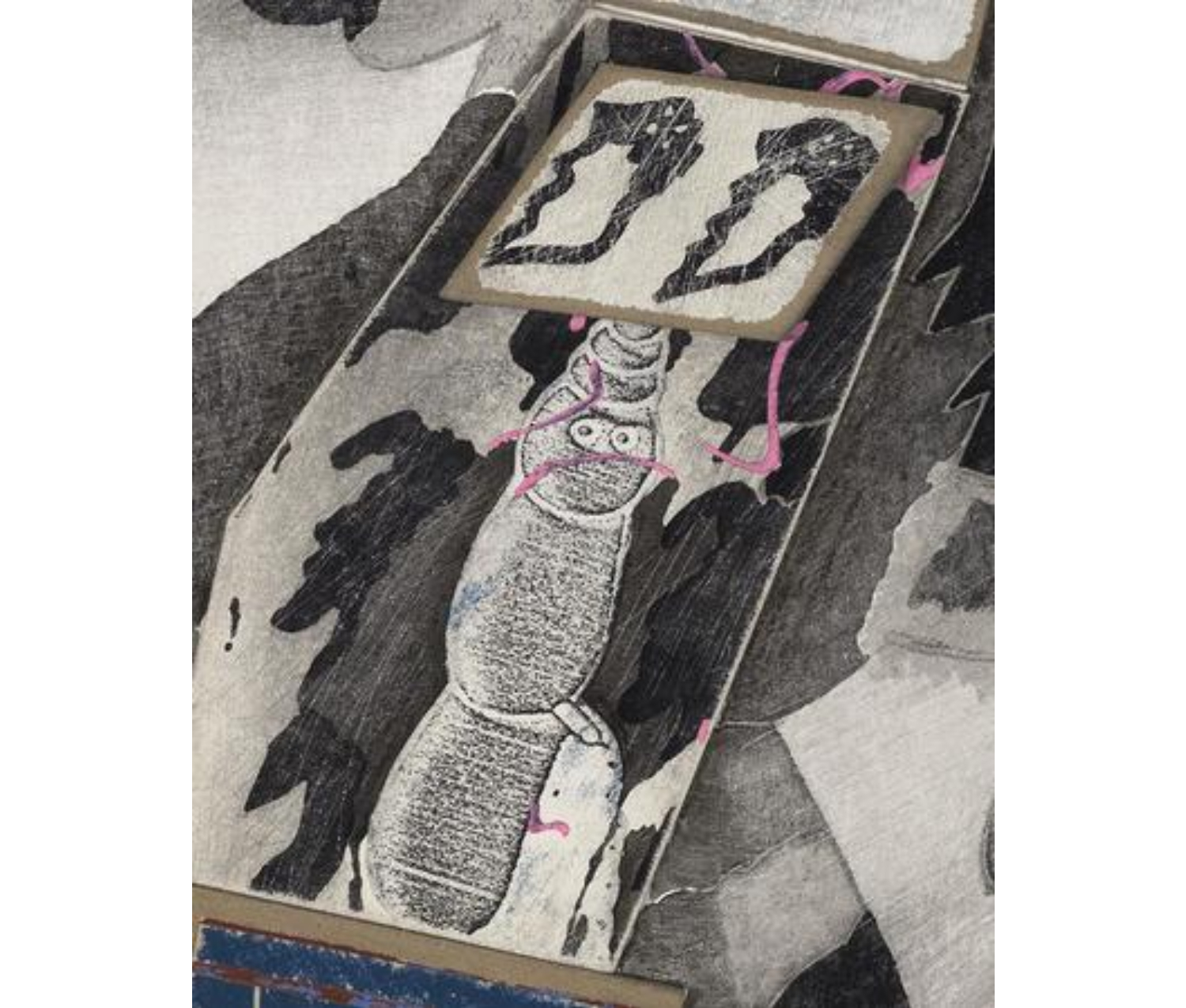

Over the years Johnson’s collages became more and more complex, often incorporating pieces of earlier works that he cut up. The second collage, Pink, features many of Johnson’s favorite motifs: a cupid, a urinating snowman, morphing black shapes, hints of text, and collaged tesserae (small pieces probably from earlier collages that Johnson has cut up, mounted, and glued on to this collage).

Ray Johnson. American, 1927 –1995. The Pink Collage, 1973. Graphite, sanding, acrylic, watercolor, gouache, ink, crayon and cardboard on thick, smooth, white paper. Promised gift from a Private Collection, Houston.

Although the cupid figure appears in many of Johnson’s collages and mail art in this example its “arrow” has been exchanged for what looks like a double headed penis or dildo. Johnson dates this collage to 1973 but dating his work can be tricky—Johnson often worked on collages for years and typically noted the dates of each edition so that a string of dates may be associated with one collage. Curiously (although not necessarily related) in 1974 Johnson’s friend, Lynda Benglis published her infamous photo spread that included a double headed dildo. At some point Johnson posed nude for Benglis in a series of polaroids holding her spectacular prop. In one he holds it up to his face like a gigantic smile.

The urinating snowmen (or Buddhas as Johnson alternatingly called them) are usually understood as a Zen reference to water and waste (or lack thereof) and the continually flowing and changing nature of the universe. While playful, like much of Johnson’s oeuvre, these figures also have ominous overtones for snowmen invariably melt, becoming water once more.

Detail of The Pink Collage

The ambiguous, continually changing black shapes throughout the collage sometimes appear zoomorphic. The five above Johnson’s signature mimic the shape of Duchamp’s Paris Air, a readymade created by asking a pharmacist to break and reseal a glass vial thus capturing some air in Paris. Johnson, who defined everything through correspondence, often quoted Duchamp’s art and ideas and situated himself as an heir of the well-known artist.

If the cupid is breathing out Paris Air, he/she is breathing in through a large pipe. This is likely a reference to one of Johnson’s other favorite French artists, Rene Magritte’s famous work Ceci n'est pas une pipe—an image that Johnson played with often in his art. Collage is a particularly appropriate medium for this reference since many times the images are physically taken from other sources (even if in Johnson’s case the other source is another of his own collages) so they are “real” rather than illusions of what they represent.

Detail of The Pink Collage

The bright pink paint in the center of the cupid’s lower head is something that Johnson added to many of his collages in 1973. A brief obsession, it really bothered some of his friends and collectors. The artist Peter Schyuff who owned this work at one time recalls feeling very distracted by the pink. Johnson sometimes did not give his collectors much choice in terms of which collages they could purchase, according to Schyuff. He would have finally saved up enough to buy something and then the only thing Johnson would claim to have available was a collage that Schyuff had issues with. Schyuff recalls: “Ray was fascinated by the fact that I didn't like this work.” Johnson’s advice when he heard that one of his friends disliked the “pink lumps” in a collage was to “paint over them with a grey wash.”

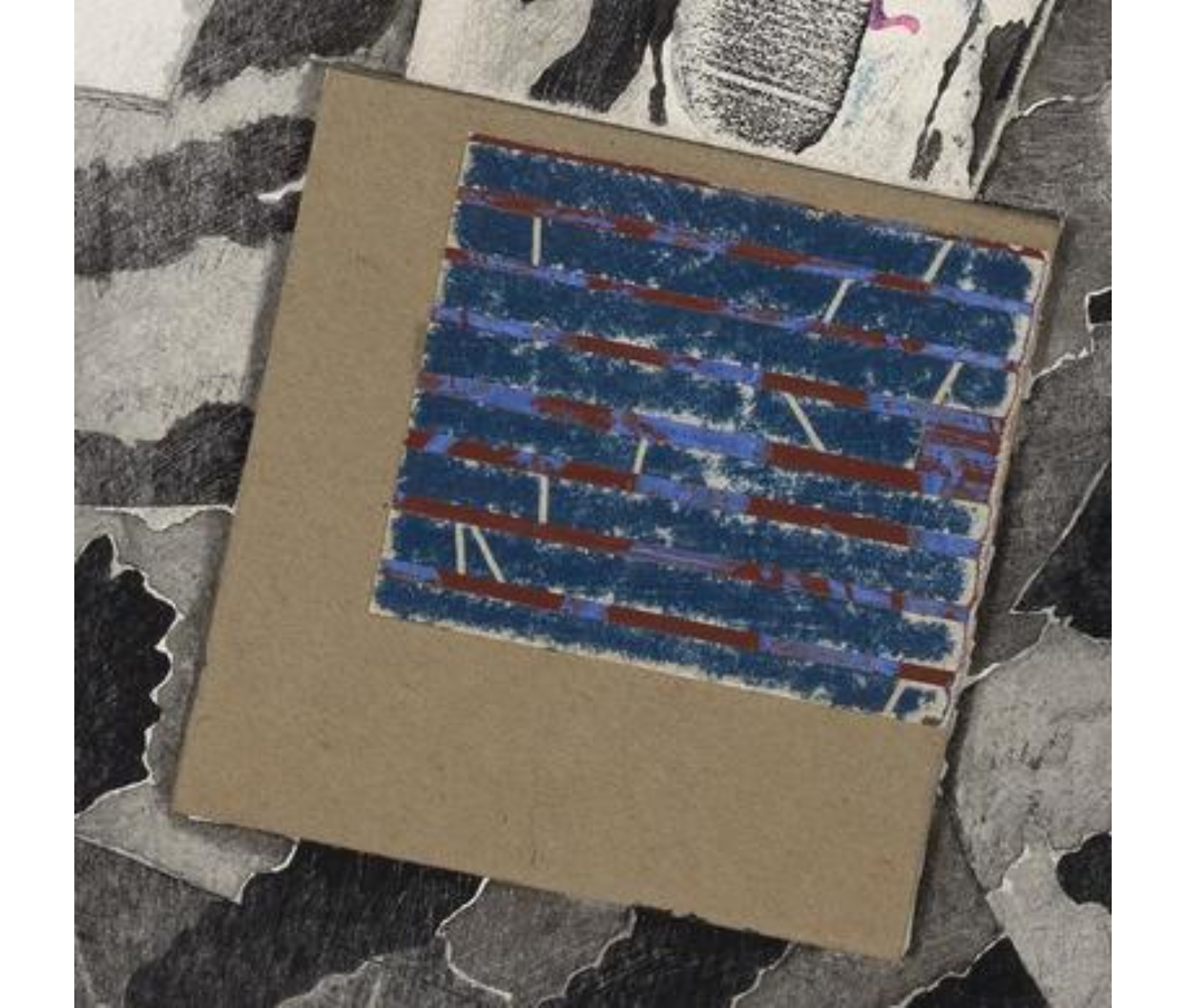

The other color in the collage, the vibrant blue at the bottom near the cupid’s knees, is most likely a fragment of one of Johnson’s early collages. He did a whole series involving cutting venetian blind-like strips, arranging them slightly off kilter, and then sanding down the paint to give them an intriguing, weathered texture.

Detail of The Pink Collage

These two collages represent very different periods in Johnson’s oeuvre—one a very unique early work, the other a more prototypical Johnson. Both are valuable additions to the Museum’s collection, offering students the opportunity to learn about an artist who is just now experiencing renewed interest from the art world. Like most artists, Johnson’s collages really come alive when you stand in front of them and can appreciate the detail, the careful craftsmanship, and the layered (both literal and figural) humor that can easily be missed in reproduction. I encourage you to come see these works for yourself!