Notes from the Curator: Mapping the City

Amanda Shubert is the 2010-2012 Brown Post-Baccalaureate Curatorial Fellow at SCMA.

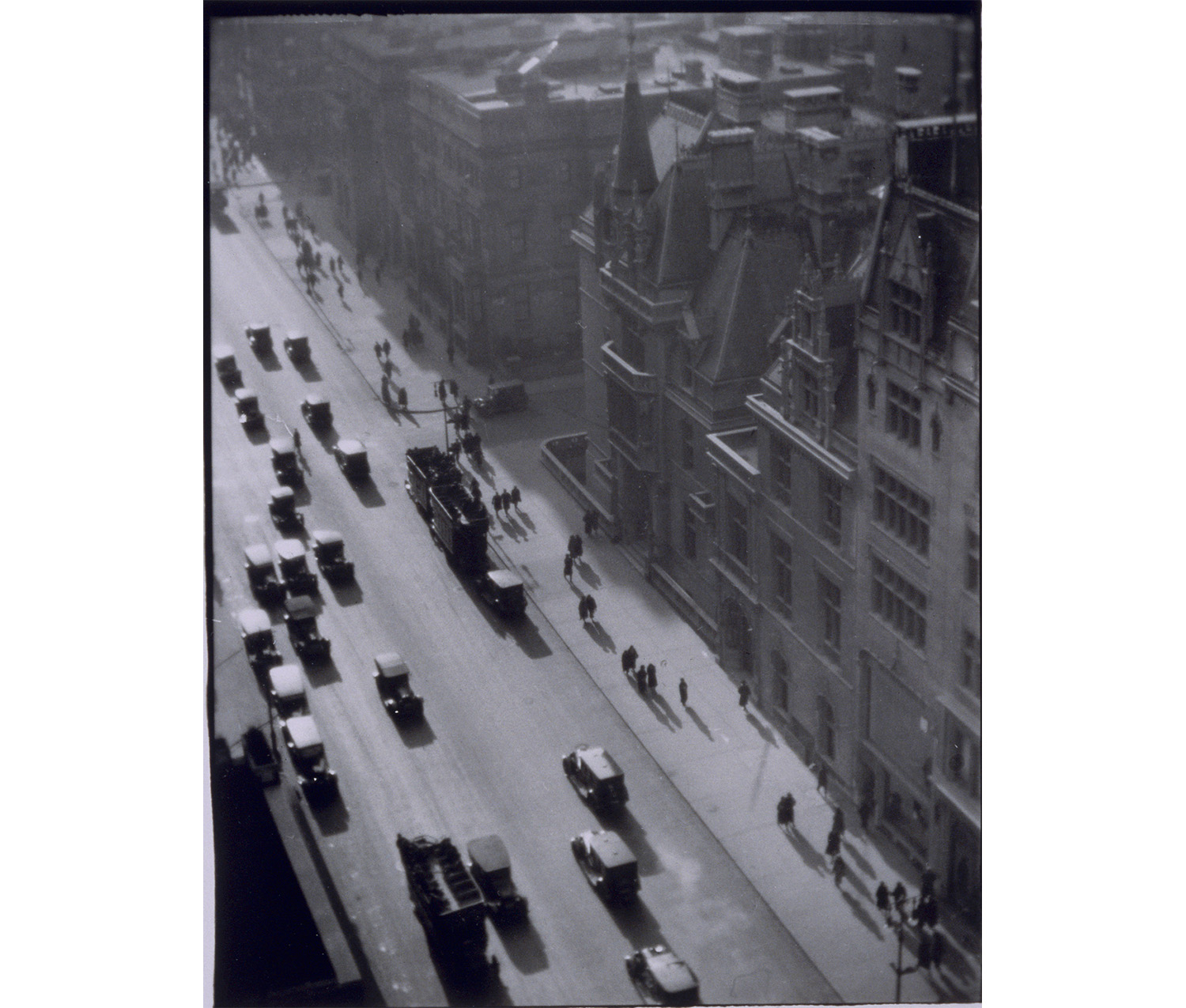

This year I became a curator for the first time: I organized a small exhibition of prints and photographs made in and about New York City in the early part of the twentieth century. I came to the topic through a fortuitous dove-tailing of ideas and events. First, I found myself learning about American prints for a separate collections research project, and as I paged through library books I became fascinated by the repetition and permutation of similar subjects: Brooklyn Bridge after Brooklyn Bridge, a myriad of skyscrapers and street corners. The documentary impulse in these works—representing real places in real time—seemed to give the landmarks they depicted a mythic stature. Second, I taught a session of a First Year Seminar called America in 1925 in which the students and I discussed the similarities and differences between two photographs of New York City, one by Alfred Stieglitz (The Terminal, 1893) and one by Ralph Steiner (Misty Day on Fifth Avenue, 1922). The students raised such provocative and compelling points about the way Stieglitz and Steiner documented urban life that I knew immediately I couldn’t let go of these works or these ideas—I would have to return to them. Third, I fell deeply and totally in love with the New York City photographs of Alfred Stieglitz and the New York City etchings of Edward Hopper, and I wanted to learn as much as possible about the work and careers of these two artists.

With inspiration like this, the exhibition came together with amazing ease. I pursued a range of work that revealed some facet of New York City life, focusing on two primary circles of artists: the printmakers associated with what came to be known as the Eight or the Ashcan School (John Sloan, George Bellows, Edward Hopper), and those associated with the more avant-garde Photo-Secession (Alfred Stieglitz, John Marin). I selected work that seemed to engage the project of documenting real people and places, the spectacles and chance encounters the city produces. I began to understand the attempt to represent the varied dimensions of an urban reality as a kind of map-making—mapping time and space, the public and the private, gender and race, industry and expansion, the nodes of human relationships and encounters that urban spaces both contain and produce. And I read whatever I could get my hands on about this topic and these artists—monographs, textbooks, and exhibition catalogs; criticism, theory, and biography.

In spite of this surfeit of research, perhaps the most fruitful lesson I learned about organizing an exhibition is that the curator doesn’t have the final word; the art does. An exhibition extends the opportunity to look at works of art in a way that is simultaneously mediated and unmediated. I made decisions about what to show and where and beside what, and I wrote a few didactic labels to direct the viewer to certain facts and interpretations, but I also felt that every work I hung was more complex than anything I could say about it. Ultimately, I recognize this as a special quality of working with original objects. The curator’s job is to allow the art to speak. And if the art can be illuminated by an argument or concept, it can also resist, complicate and transcend the argument or concept. I loved working in this unsettled state.

Ralph Steiner. American, 1899–1986. Misty Day on Fifth Avenue, from Portfolio III: Twenty-two Little Contact Prints from 1921 - 1929 Negatives, negative 1923; print 1981. Gelatin silver print mounted on paperboard. Gift of Thomas R. Schiff. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1984.25.3.

Hanging the exhibition

The exhibition Mapping the City is on view in the Cunningham Center corridor through September 25.