Now You See Me

The Smith College Museum of Art is dedicated to bringing out works on paper into the main galleries, where all visitors can see them. Since works on paper are more sensitive to light than other mediums, SCMA has installed special Works on Paper cabinets throughout the galleries for the display of prints, drawings and photographs. Guest blogger Janna Singer-Baefsky, class of 2015, curated the current installation of the second floor Works on Paper cabinet, titled Now You See Me: The Relationship between the Printed and Painted Portrait. It will be on view through June 2015.

Janna Singer-Baefsky ‘15 sets out her labels for her Works on Paper cabinet

In two sentences, French poet and art critic Charles Baudelaire captures the inherent paradox of portraiture: “Nothing in a portrait is a matter of indifference. Gesture, grimace, clothing, decor even – all must combine to realize a character.” Portraiture, a seemingly biographical and documentary genre, is often more farce than fact. Every aspect of monarchical portraiture, for example, was constructed by the sitters to display not only their opulence and grandeur but also their power and control, both believed to have been given by God.

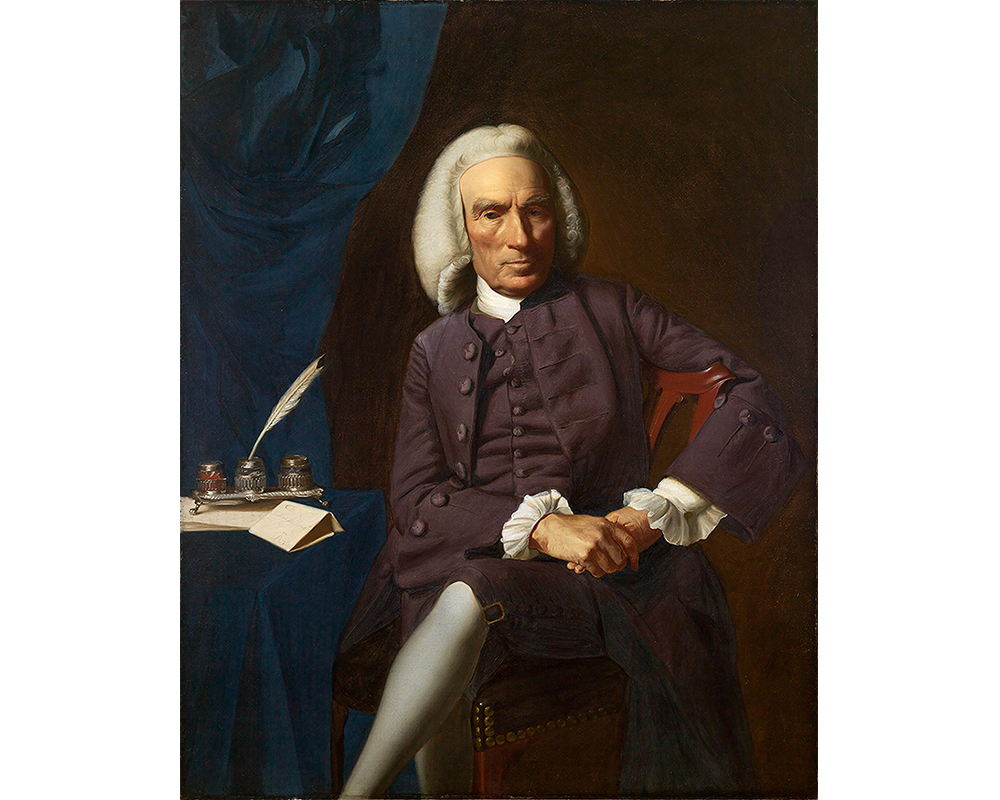

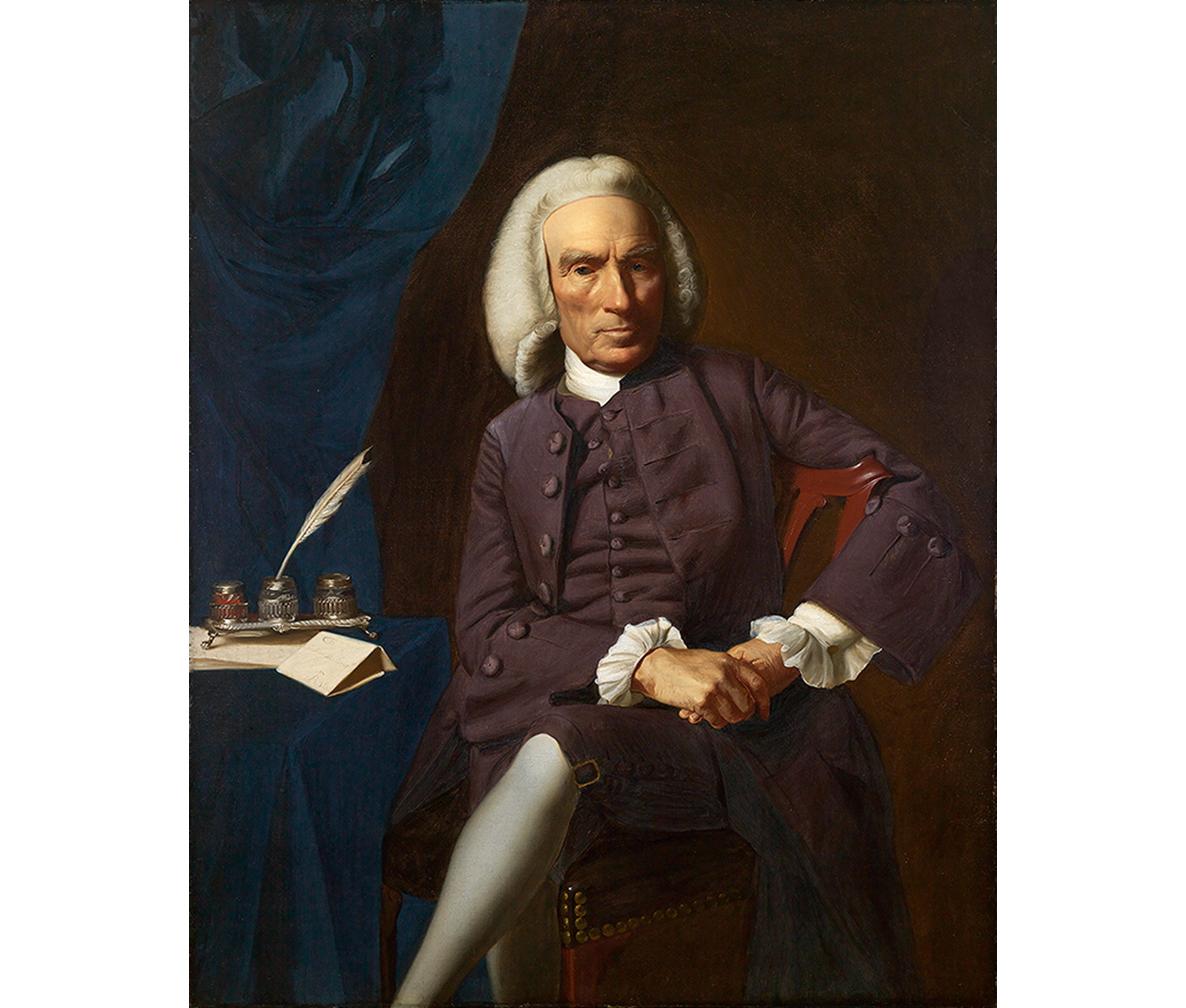

Portraiture did not die out as the age of monarchs came to a close. Instead it reinvented itself to cater to the needs of the colonists. Coming from a European tradition, the tenets of portraiture remained; it was still the primary method of documenting success. Only now, in the democratic colonies, portraiture illustrated social mobility. It was the genre of the upper-middle working class and so merchants, tradesmen, and lawyers all utilized portraiture to show they were well-traveled, literate, and cultured gentlemen. Serving somewhat as a pictorial “take that, King George!,” portraiture became less about divine authority and more about displaying social advancements.

John Singleton Copley. American, 1737–1815. The Honorable John Erving (1693-1796), ca. 1772. Oil on canvas. Bequest of Anne Rutherford Erving, class of 1929. SC 1975.52.1

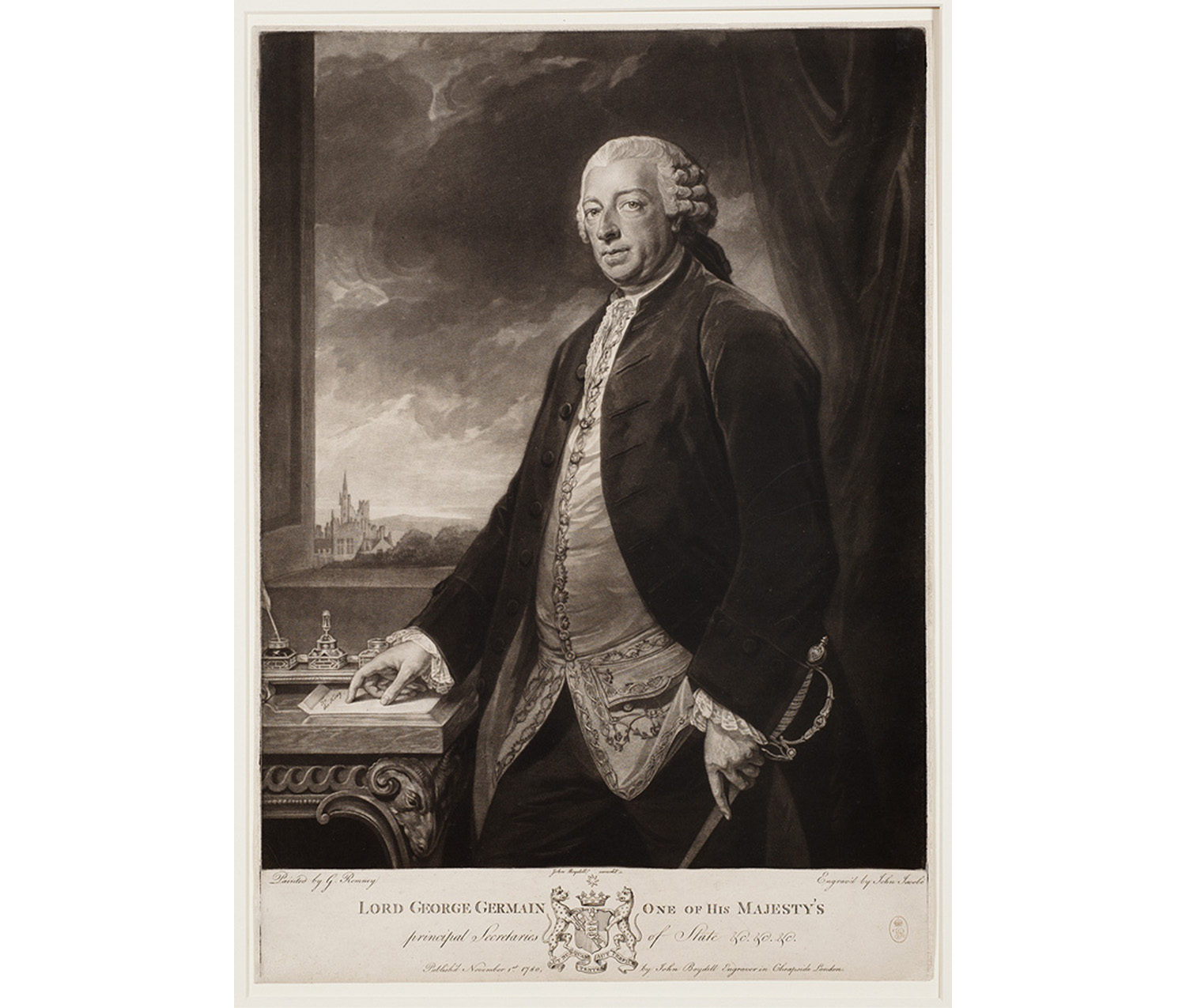

Johann Jacobé. Austrian, 1733–1797. After George Romney. British, 1734–1802. Lord George Germain, 1790. Mezzotint on ivory laid paper. Bequest of Henry L. Seaver. SC 1976.54.380.

The stories and subtle nuances contained within a seemingly simple image have made portraiture one of my favorite artistic genres. Thus, when I was given the opportunity to propose and curate an exhibition for my museum studies capstone I decided to delve into portraiture. I have spent two years working in the Cunningham Center for Prints, Drawings, and Photographs so it was only fitting to propose something that allowed me to work with a collection with which I had spent so much time fostering a personal relationship. Having had the privilege to conduct extensive research on mezzotints at the Smithsonian Institute’s National Museum of American History, this exhibition would also function as a testament to my scholarship.

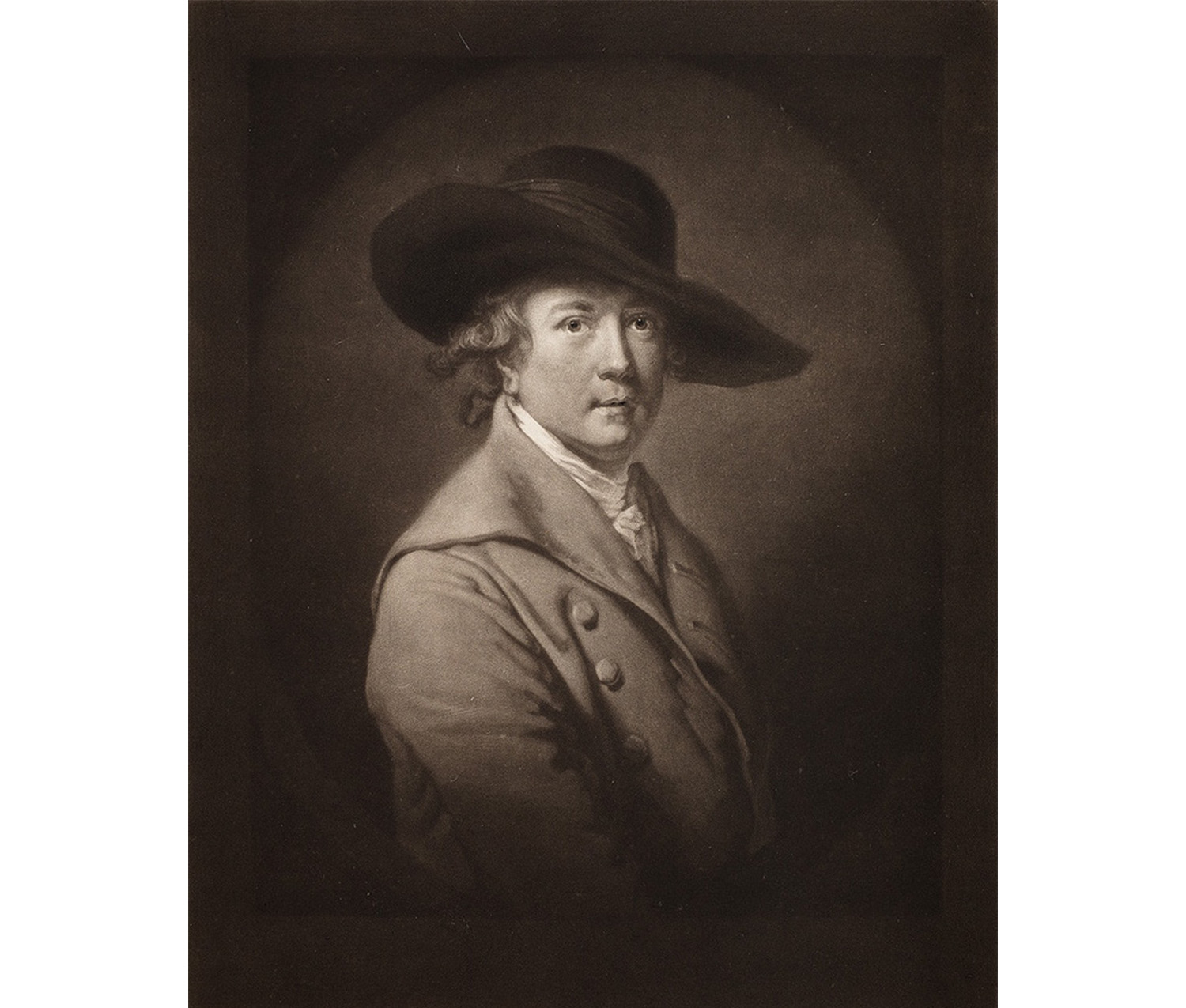

James Ward. British, 1769–1859. After Joseph Wright. British, 1734–1797. Joseph Wright, Esquire, 1807. Mezzotint on paper. Purchased. SC 1953.17.

Joseph Wright of Derby. Self Portrait. 1780. Oil on canvas. Yale Center for British Art (image source)

The mezzotint, a tonal form of printmaking, gained fame and popularity in the 18th century due to its ability to render the three-dimensionality and qualities of oil paintings. Situated in the second floor portrait gallery, the mobile cabinet contains six mezzotint portraits made after oil paintings. It is a media comparison through one genre. It is an exhibition about portraiture that is itself a portrait of my four years at Smith.

Janna Singer-Baefsky ‘15 places a print on the top of her Works on Paper cabinet

Find Now You See Me: The Relationship between the Printed and Painted Portrait on the second floor of the Museum through June 2015.