Objects in Limbo

Guest blogger Saraphina Masters is a Smith College student and the 2013-2015 STRIDE Scholar in the Cunningham Center for Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

The concept of “limbo,” of objects existing without information in an art museum, is discordant with the casual observer’s perception of fine arts institutions. Don’t we live in an age of digital databases and intense organization, both of which ought to prevent the displacement of any work of art? A look behind the scenes, however, can show how easily human error or simple forgetfulness can lead a piece of art into limbo, into an existence without cataloging, captioning, or even a proper home.

Since time is such a large factor in this concept, it makes sense to mention the evolution of collecting and cataloguing in museums. Early catalogue systems were simply note cards and filing cabinets, while today we use electronic databases and software. Additionally, the value of a piece can, and often does, change over time. That can affect the way it is catalogued and handled, which can in turn lead to its misplacement. These variables and more all contribute to the story of an object and how it ended up where it was when I found it.

My work with a box of loose prints, which I refer to as Box B2, led me down multiple rabbit holes of research and intrigue. My task was to gather as much information on each piece as possible. This collection of seemingly random prints came with varied levels of information. Some were clearly and helpfully labeled, while others came with nothing at all. My first steps were translating captions in other languages, deciphering antiquated handwriting, and making educated guesses about origin and style.

Then, the unexpectedly intense research process comes in. Simply googling the words on a print can produce some results, if the piece is relatively well known or unique. However, many of the prints were too obscure or unforthcoming for such an easy solution. This is where databases such as that of the Five College Museums and the Getty Research Institute’s searchable list of artists’ names, ULAN, can be useful. These resources, in addition to auction results and historical websites, make the investigatory task of information gathering possible.

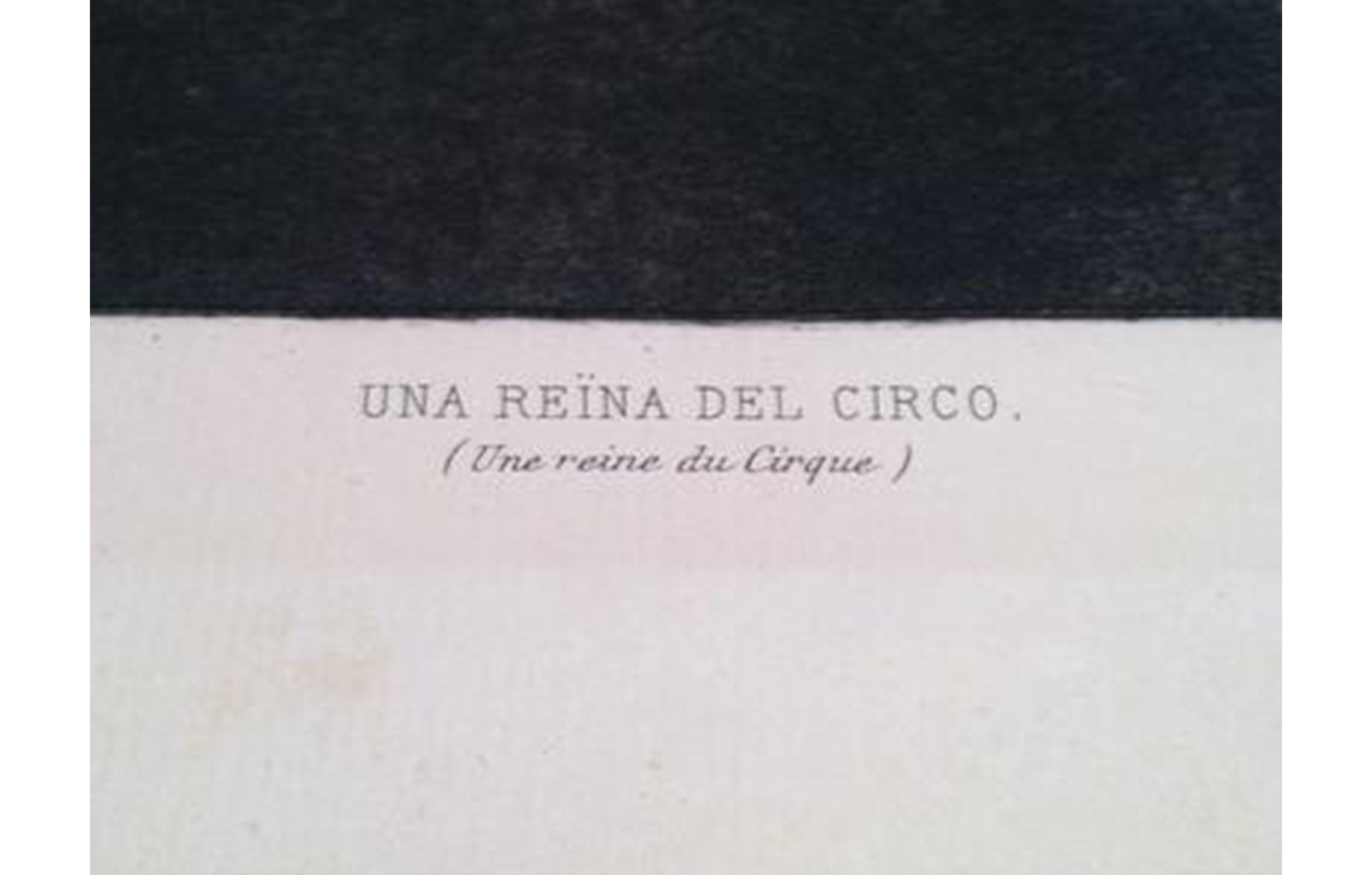

One particular print that required quite a bit of research was a Goya etching that upon first examination seemed to be called Una Reïna Del Circo. Translated as The Queen of the Circus from Catalan, I assumed the caption of the piece to be the title. However, I went to Hillyer Art Library to find out more about the etching and after looking in quite a few books on Goya, I recognized the image of the etching under a different name.

This piece is actually called Disparate puntualor, or Precise/Sure Folly, and is part of Francisco de Goya’s 18 piece series called Los Proverbios; in English, the Proverbs or the Follies. From there I was able to move forward with my research, trying to find out more about its origin and how it came to the museum. The confusing labels, as well as the multiple translations, made this story layered and complex. Uncovering information about this print took more than simple observation. Like much art historical research, multiple sources, including auction sites, textbooks, and the Cunningham Center itself, were used to learn more. This Goya print has quite a story, only a fraction of which played out in my examination of it.

Each work has a narrative as engaging and complicated as the Goya print, and there is a whole box of them, in addition to other unidentified prints in museum. Perhaps that provides an idea of the scope and quantity of suspended objects that are unknown in origin. In Box B2 there was an entire sheaf of prints that was labeled “The following were found in a closet in a campus security office in 1989”. We may never know how those works of art came to be in that closet, and who put them there. What matters is that we have them now, and can do our best to find out what we can about them. Little by little, we can pick away at the indeterminate “limbo” of objects, and through research bring the histories of lost pieces to light.