Odd Couples: Venus vs. Eve

Henriette Kets de Vries is the Cunningham Center manager and Assistant Curator of Prints, Drawings and Photographs.

Marcantonio Raimondi. Italian, ca. 1482–ca. 1534. Venus and Adonis, n.d. Engraving on paper. Purchased. SC 1940.16.1. Photograph by Petegorsky/Gipe.

The Cunningham Center harbors a wonderful collection of old master prints that is especially strong in the area of Northern European Renaissance works. One of the eye-opening experiences you can have when working with old master prints is uncovering their insights into the history and philosophy of a past culture.

The portability of prints in the early Renaissance made them the perfect medium to propagate cultural beliefs, as well as subjects and trends in art. Prints travelled easily and were relatively affordable, enabling a cross-pollination of art and ideas between northern and southern Europe. Relatively egoless, printmakers of the early fifteenth century readily shared with and copied works from other artists. One such well-known and respected copyist was Marcantonio Raimondi, considered an important innovator in the history of Italian printmaking. While most Italian printmakers of the time copied directly from known painted works, Raimondi was also famous for his free interpretations of works by other artists.

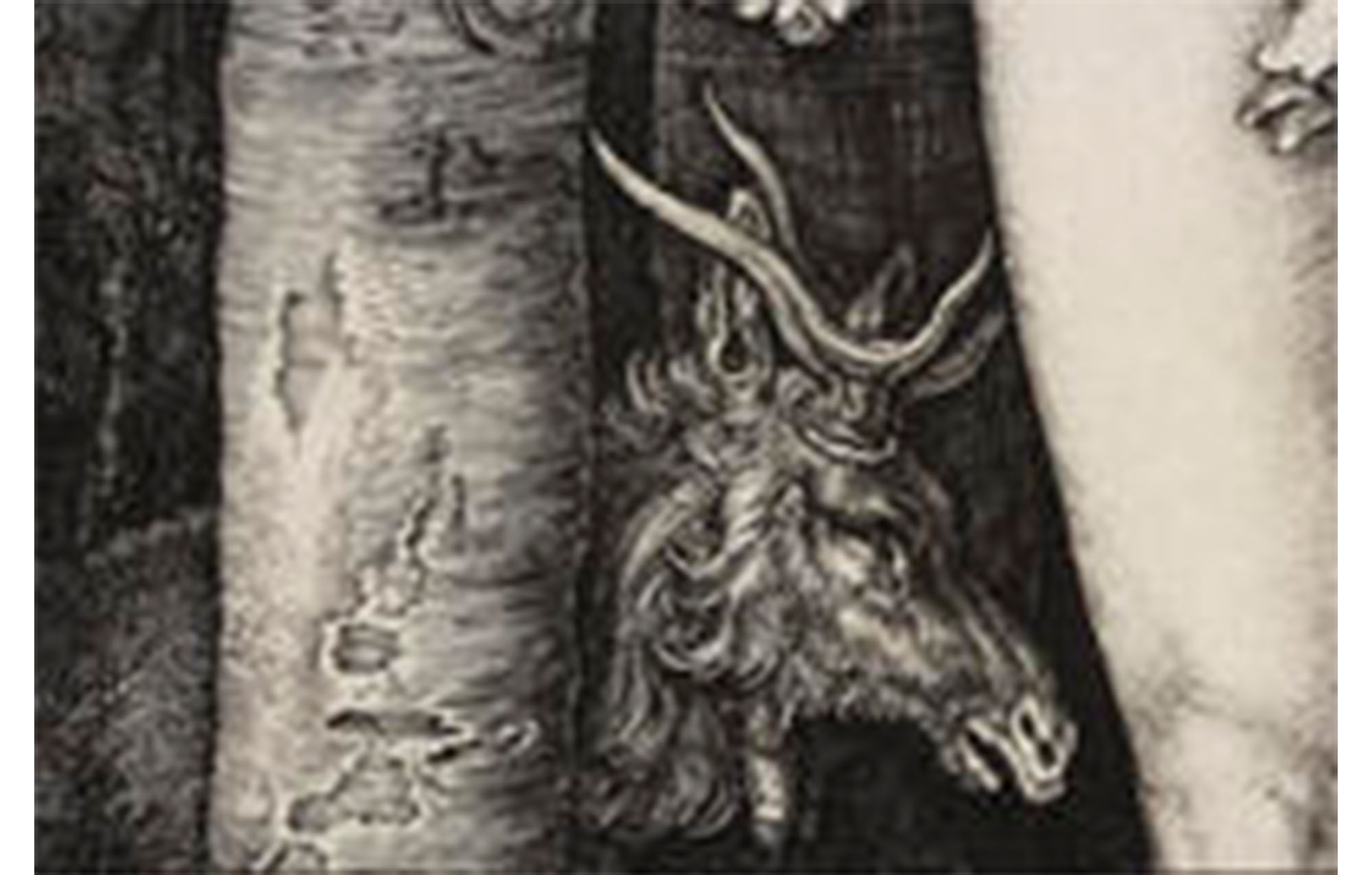

Raimondi’s Venus and Adonis is a fascinating example of this practice. Raimondi re-works portions of Adam and Eve, an engraving by the famous German artist Albrecht Dürer. In Venus and Adonis, Raimondi depicts a nude man and woman situated in a landscape composed similarly to Dürer’s in Adam and Eve, and directly copies Dürer’s lazy-eyed stag, which appears in both prints from behind a centrally located skinny tree.

Detail from Adam and Eve

Detail from Venus and Adonis

In a way, these iconographic borrowings transform Raimondi’s Venus and Adonis into a southern “pagan” equivalent to Dürer’s northern Christian Adam and Eve.

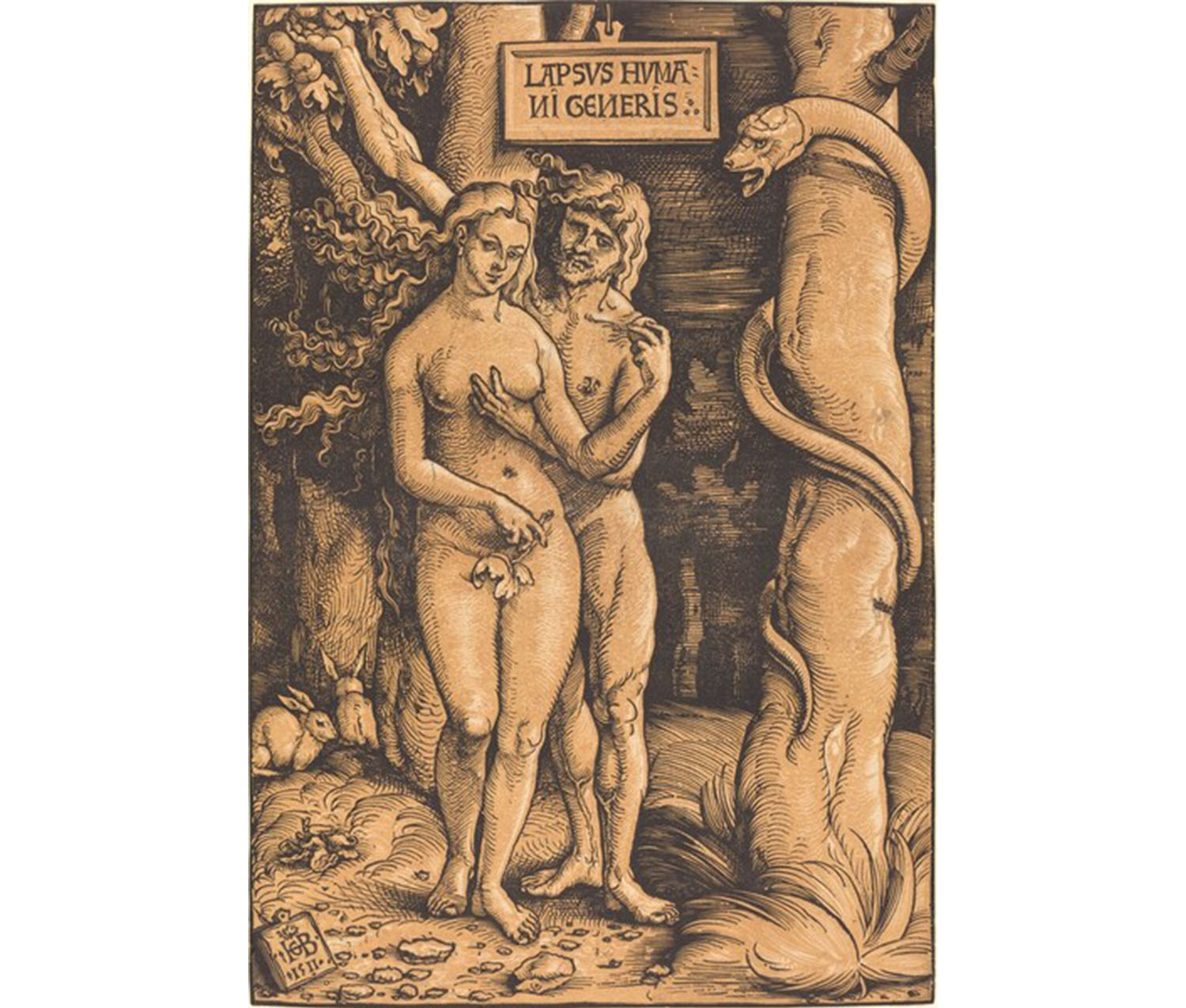

The correlation between Adam and Eve and Venus and Adonis is not as farfetched as it may seem at first glance. In Ovid’s story of Venus and Adonis it is Venus who actively seduces Adonis. Often portrayed as a manipulative seductress, Venus’s attributes were easily transposed onto the biblical Eve, who, according to Saint Augustine (354–430), probably the most influential Christian theologian of all time, used her womanly charms to entice the innocent Adam into sin, ultimately leading to the Fall of mankind.

That Eve used her womanly charm to achieve this feat leads us to an interesting detail that connects the two stories in these prints even further. In Raimondi’s print, Adonis is holding Venus’s breast. The breast is easily confused in this context with the seductive round apple Eve offers to Adam, a correlation that has been made in other works of art.

Hans Baldung Grien. German, 1484/85–1545. Adam and Eve, 1511. Chiaroscuro woodcut. Rosenwald Collection, National Gallery of Art, Washington. 1943.3.907.

Comparing these two works by Raimondi and Dürer reveals how artists of the time made interpretive choices to convey cultural and religious ideas, in this case regarding the cunning and destructive sexual power of women—an idea that had currency in both northern and southern Europe, and that unfortunately still resonates in our time.