An Old Man Mad About Art

Guest blogger Anya Gruber is a Smith College student, class of 2016, with a major in Art History. She was a Student Assistant in the Cunningham Center for Prints, Drawings, and Photographs.

The painter Hokasai was given the name Katsushika Hokusai, but repeatedly reinvented himself by taking on new names throughout his life. Each time, these rebirths were followed by a renewed artistic style and spirit. When he was young and first started studying under the famous Japanese artist Katsukawa Shunshō, Hokusai called himself Shunrō, adopting the last letter of his master’s name. After adopting a half a dozen other names throughout his youth and middle age, he began to call himself Gakyōjin. Gakyōjin means ‘an old man mad about painting,’ a fitting epithet for an artist who was absorbed in perfecting his craft, and hardly ceased to continue learning and reinventing himself.

Hokusai was born in 1797 in Edo, a pastoral region of Japan, during the Tokugawa Shogunate. Nakajima Ise, a silver polisher, took a very young Hokusai under his wing. With the help of Nakajima, Hokusai found an assortment of different apprenticeships which apparently didn’t work out for him; by age 15, he moved out of the Nakajima household (though his adopted family remained very dear to him) and found himself working under Katsukawa Shunshō. Here, he mostly helped make portraits of the famous actors of the time. After fifteen years or so, the Katsukawa School began to lose prominence, and Hokusai left to continue making art on his own, and to illustrate novelettes. He began to intensely study a great variety of artistic traditions, including Dutch engravings. Hokusai’s interest in Western-style art had a great effect on his own work and set him apart from his contemporaries.

Beginning in 1753, Hokusai produced many western-influenced pieces that mainly depict landscapes of his hometown, the rural and rugged Edo. Most of the works from this time are created with a perspective that is unusual for traditional Japanese art, and Hokusai employed characteristically European techniques, such as chiaroscuro, which is so closely associated with Renaissance art.

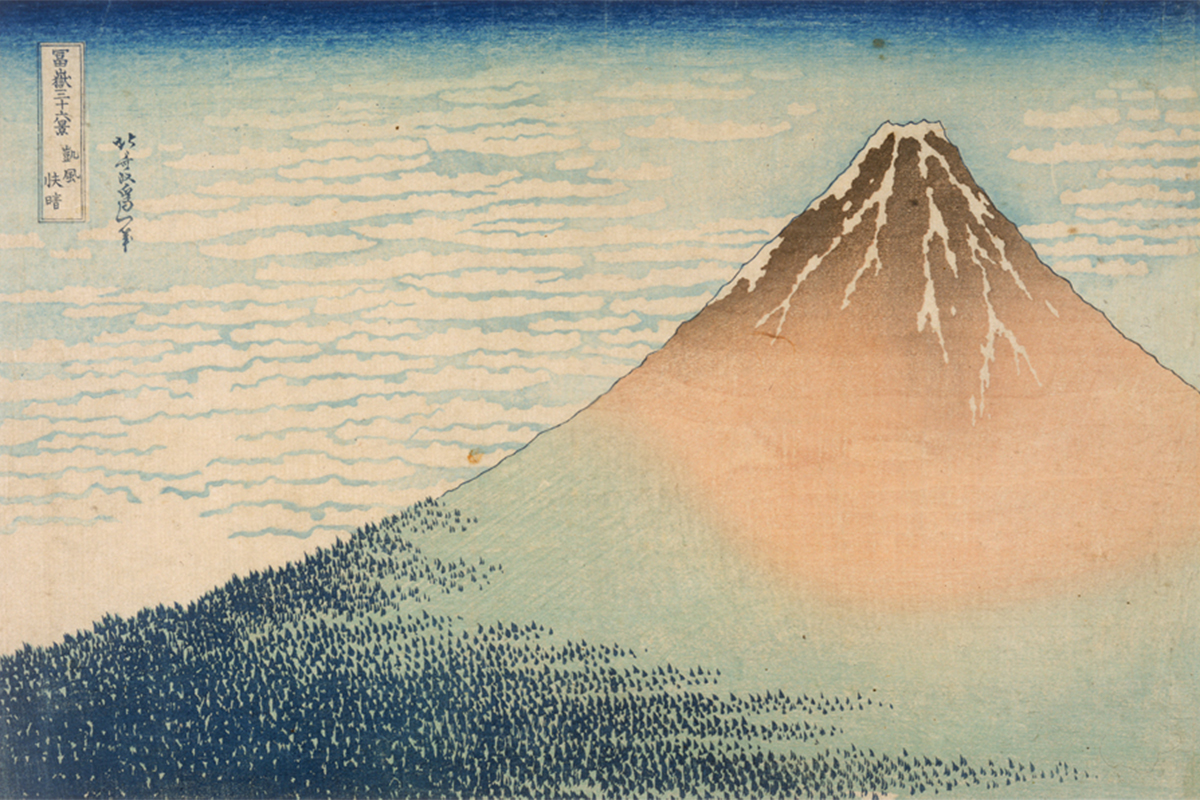

The Cunningham Center has a number of Hokusai prints that exhibit Hokusai’s characteristic blend of East and West. The print below, entitled Suruga Street at Edo, comes from the series Thirty-Six Views of Mt. Fuji. Here, you can see how the sky in the background is softly shaded, and the mountain are stark but still natural-looking. Here, you can see how Hokusai uses on low view point, which was a very Western technique, rather than a more traditionally Japanese flat viewing plane.

Katsushika Hokusai. Japanese, 1760–1849. Suruga Street in Edo, the Mitsui Shop, No. 21 from Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji, ca. 1832. Woodcut printed in color on paper. Gift of Mrs. Arthur B. Schaffner in memory of Louise Stevens Bryant, class of 1908. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1959.268

As he grew older, Hokusai became more and more prolific. He predicted in his autobiography that by the time he was an aged man‘each dot, each line shall surely possess a life of its own.’ By this, I think he meant that by devoting his entire life to his art, his work would be animated so much by his own passion, it would gain its own life. When he was seventy-four years old, he wrote that he thought that no works he produced before the age of seventy were any good; he pushed himself incessantly to become the best artist he could. He was rather an embodiment of the stereotypical artist, in fact; he was focused on his art, and his art only. He lived up to his name Gakyōjin, as he became rather eccentric, still changing his name and moving to new cities in a restless search of perfection. He prayed to live to at least one hundred years old and, in honor of that hope, he created a new seal which read ‘hyaju,’ or ‘one hundred.’ However, he passed away at the age of eighty-nine. Though his life had not spanned a century (as he had hoped), he left behind an incredible trove of artwork and is still renowned not only in Japan but throughout the world.