From our archives: The Age of Mezzotint

Julie Warchol was our 2012-2013 Brown Post-Baccalaureate Curatorial Fellow in the Cunningham Center and now works as the Collection and Exhibition Manager, Arts of the Americas, at The Art Institute of Chicago.

Before the invention of the camera in the 1820s and the even more recent explosion of digital photography and the Internet in the 1990s, printmaking was the only means of reproducing and disseminating images in large quantities. While many printmakers throughout history created original compositions and were famous in their own right, some teamed up with painters to reproduce their paintings in great numbers. For both the painter and the printmaker it was a mutually beneficial partnership which increased the reputations of both artists through the broad distribution of these prints after paintings.

Mezzotint, a printmaking technique invented by the German amateur artist Lugwig von Siegen in 1642, created unprecedented capabilities for translating paintings into prints. Its name comes from the Italian mezzo-tinto, meaning “half-tone” Mezzotint is the first intaglio technique which could create a range of shades between black and white without the exclusive use of lines, such as the cross-hatching of engraving and etching. Mezzotint is also unique in that the artist creates the image from dark to light. The metal printing plates are first worked with an instrument called a “rocker” to create the darkest tone. The mezzotint-engraver subsequently scrapes particular areas which will print in shades of gray or, finally, the brightest white. (Click to see videos of a mezzotint-engraver performing these first and second stages in the process.) Mezzotints are characterized by their velvety blacks and incredibly rich tones, which make mezzotint an ideal print medium for meticulously recreating the soft manner and texture of paintings. However, for this reason, mezzotint (unlike engraving and etching) was rarely used by artists to create original compositions.

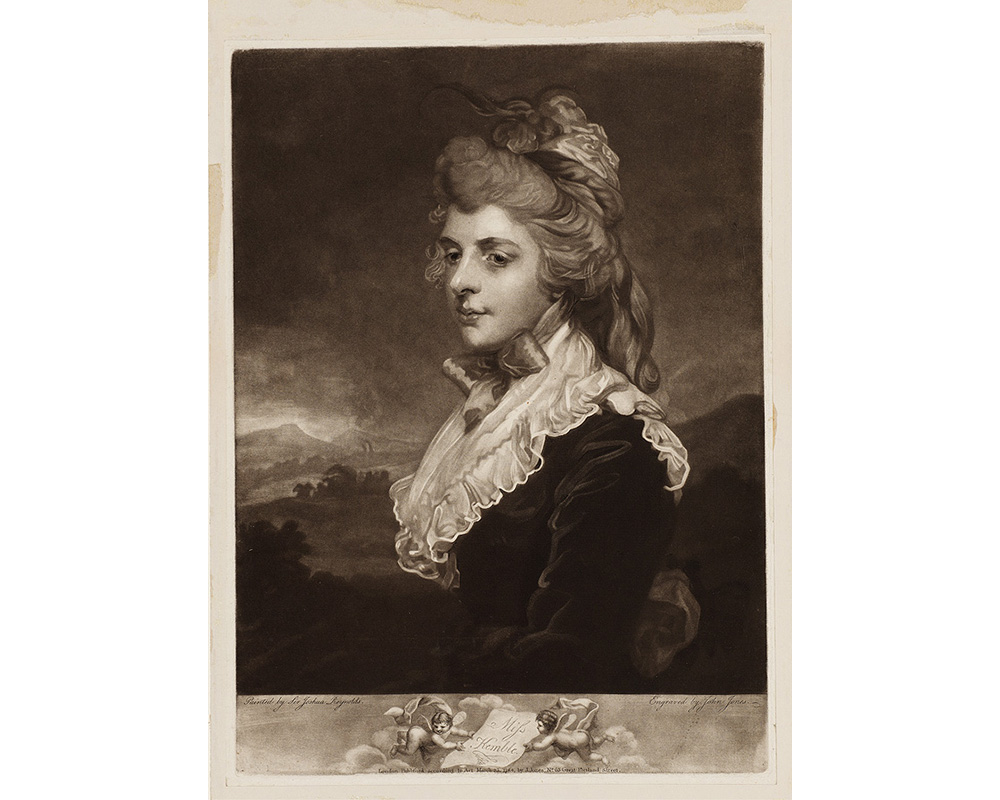

James McArdell; after Joshua Reynolds. British, McArdell ca. 1729–1765; Reynolds 1723–1792. Mrs. Turner of Clints in Yorkshire, n.d. Mezzotint on paper. Gift of Clara Culver Gilbert, class of 1892. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1953.76.

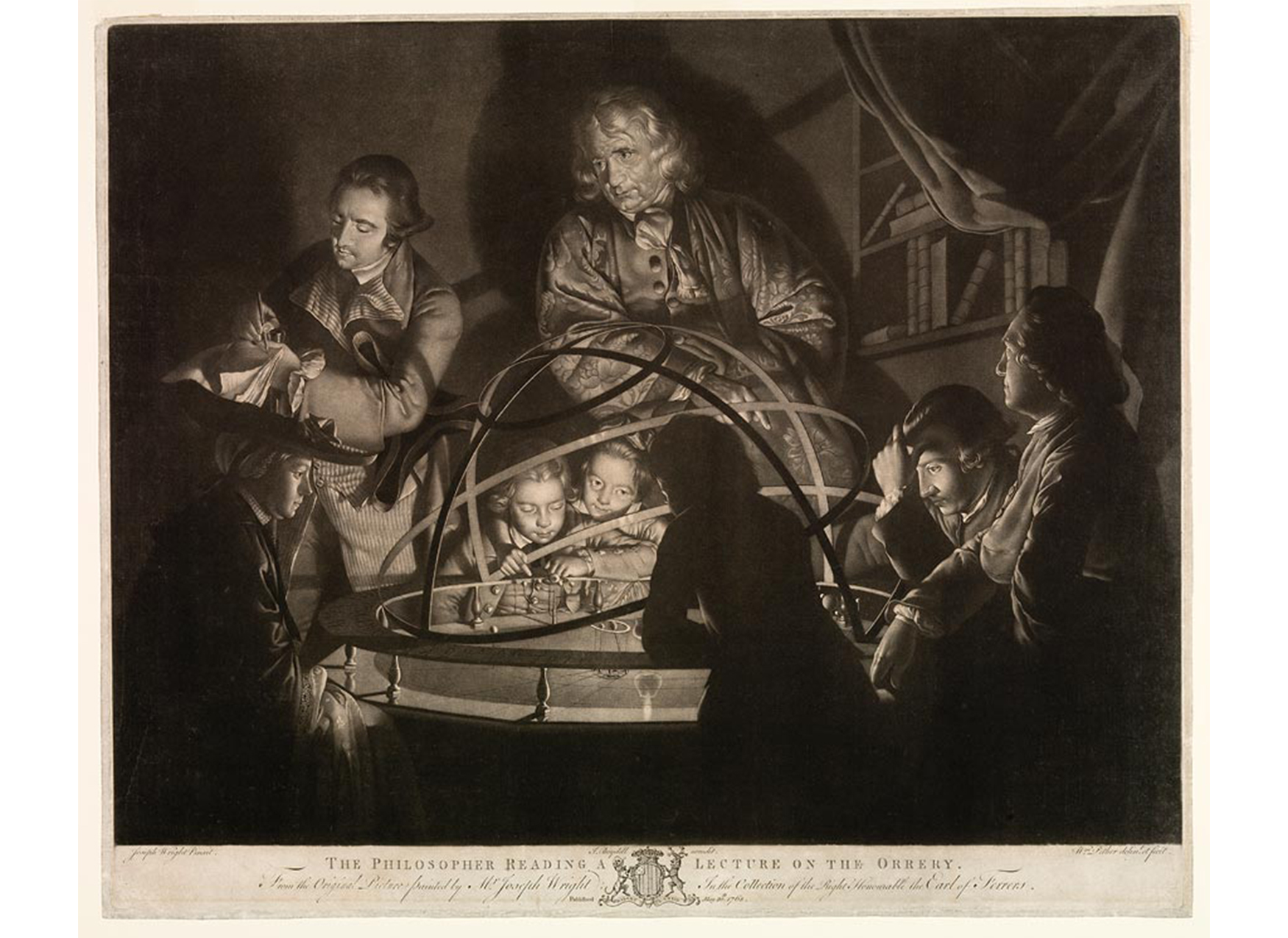

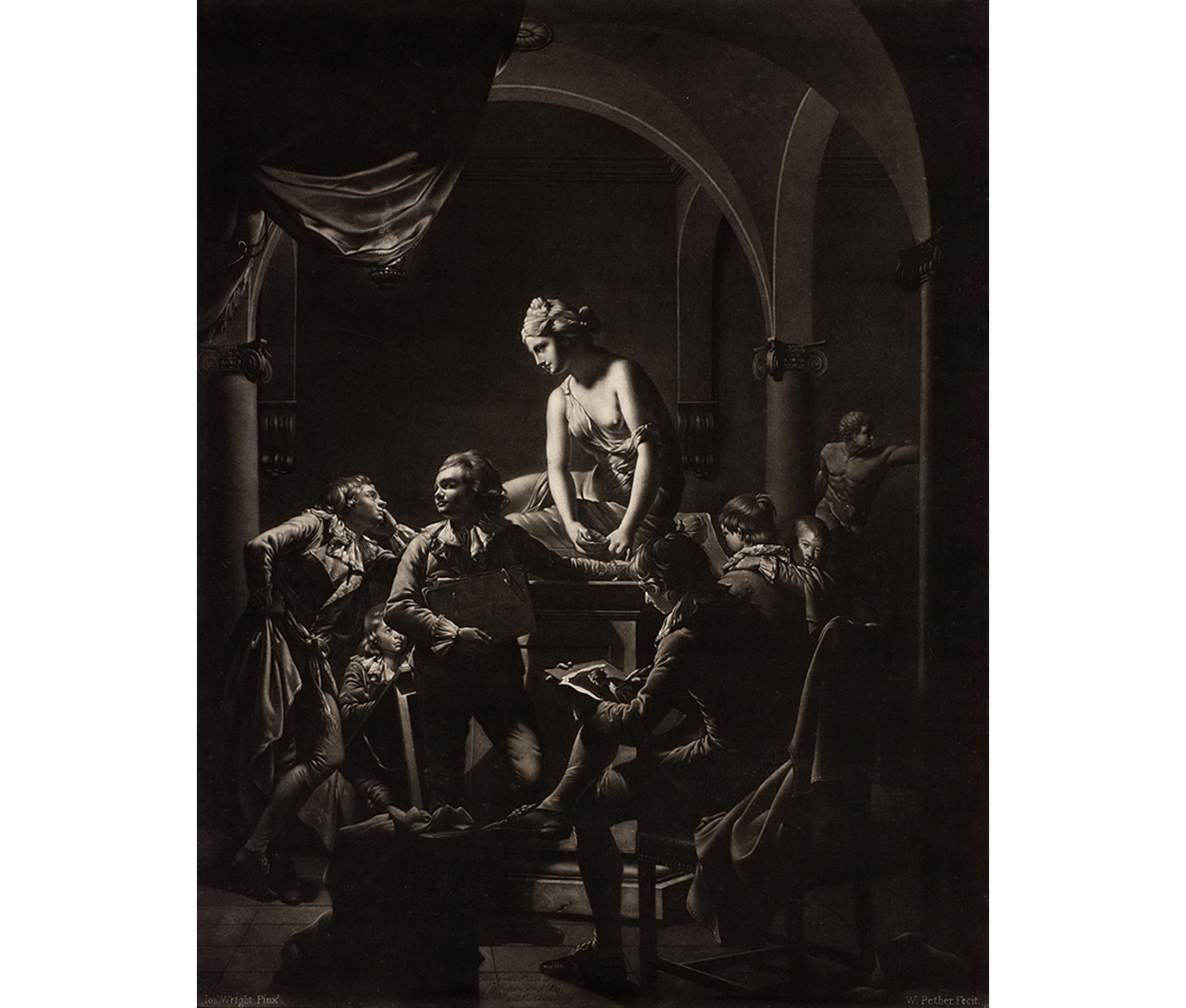

Mezzotint reached its peak in popularity during the 18th and early 19th-centuries, mainly in Britain. In the 18th-century, prints after paintings by such famous British painters as Sir Joshua Reynolds (above) and Joseph Wright of Derby (below) circulated throughout Europe, increasing the visibility and reputations of these artists. The mezzotint technique brilliantly captures and translates the elegant, flowing clothing of Reynolds’ British nobility portraits as well as the dramatic chiaroscuro(light-dark) contrast of Wright’s scenes which depict the Age of Enlightenment. Mezzotint-engravers were often known for their unique skill in transcribing the work of particular painters, such as British mezzotint-engraver William Pether’s reputation for recreating Joseph Wright of Derby’s paintings.

William Pether; after Joseph Wright (Wright of Derby). British, Pether 1731/38–1821; Wright 1734–1797. A Philosopher Reading a Lecture on the Orrery, 1768. Mezzotint on paper. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1953.16.

William Pether; after Joseph Wright (Wright of Derby). British, Pether 1731/38–1821; Wright 1734–1797. An Academy by Lamplight, 1772. Mezzotint on paper. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1954.44.

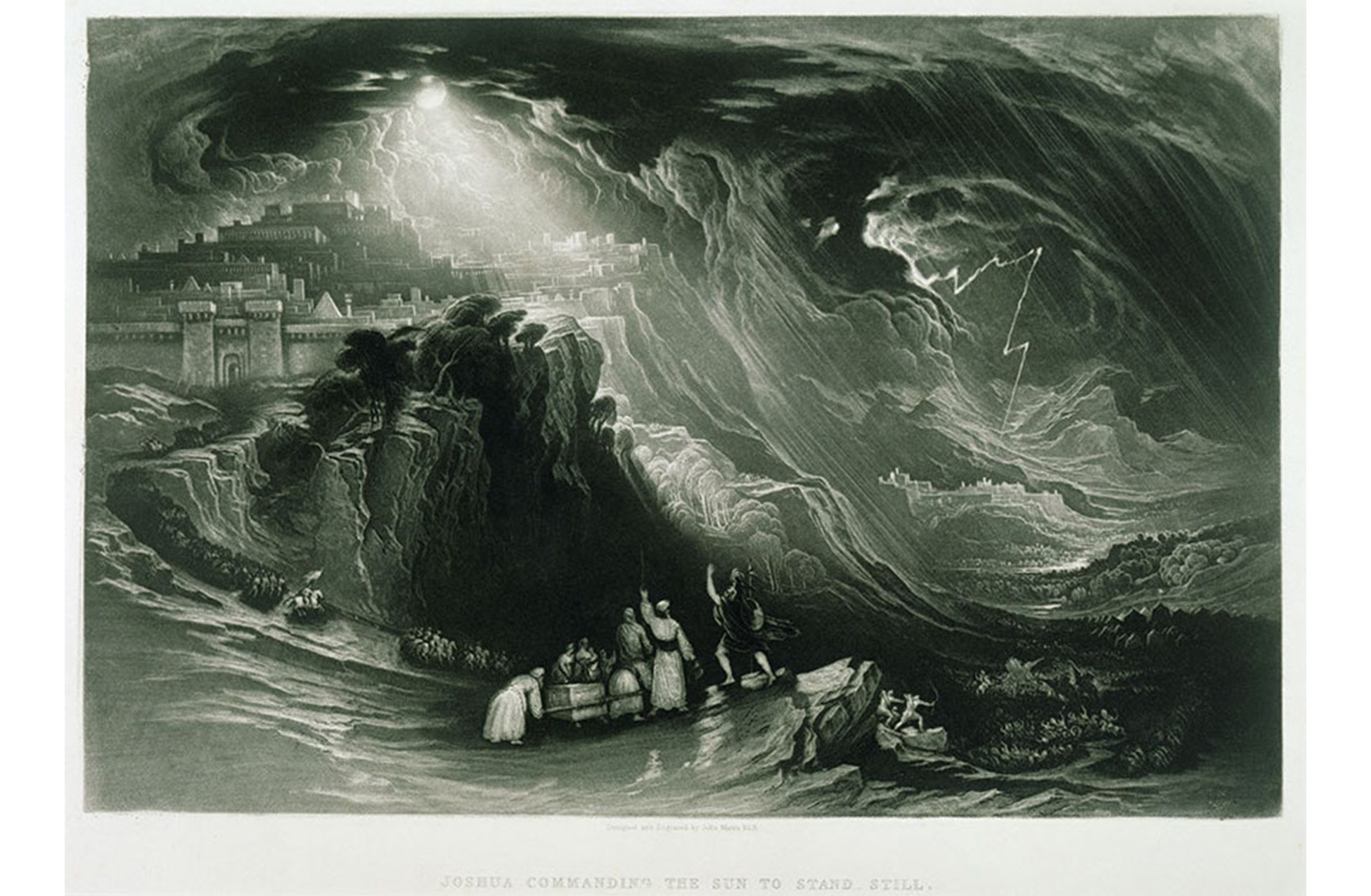

By the early nineteenth century, mezzotint was appropriated by a new generation of British painter-printmakers, such as J.M.W. Turner and John Martin (both shown below), who were both more devoted to depicting landscapes than figures. Unlike their predecessors, Turner and Martin were painters and mezzotint-engravers who used this print medium for original expression. Turner was particularly successful for his work in both painting and printmaking. His collection of seventy landscape mezzotints called Liber Studiorum(Book of Studies) was very widely circulated. Both Turner and Martin exploited mezzotint’s capabilities to create expressive landscapes, full of drama and motion.

Mezzotint fell out of style by the middle of the 19th-century, perhaps in favor of other printmaking techniques, because of the invention of photography, or other unknown reasons. Regardless, this idiosyncratic technique, which beautifully transcribes the softness, expressiveness, and motion inherent to painting, serves as a reminder to us today of the importance of and skill behind creating reproductions before the age of photography.

John Martin. British, 1789–1854. Joshua Commanding the Sun to Stand Still, from Illustrations of the Bible, n.d. Etching and mezzotint on white wove paper. Purchased. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1968.44.

Joseph Mallord William Turner. British, 1775–1851. The Deluge, Plate 82 from Liber Studiorum, n.d. Mezzotint on cream-colored wove paper. Bequest of Henry L. Seaver. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1976.54.288.