Pandora's Box

Guest blogger Nathan Rubinfeld is a participant in the 2012 Summer Institute in Art Museum Studies at Smith College and a 2012 graduate of Hampshire College.

Master ZBM’s exquisite print, Pandora’s Box or An Allegory of Les Sciences qui Éclairent l'esprit de l'homme (The Sciences that Illuminate the Human Spirit) is an ideal point of entry into the Summer Institute in Art Museum Studies’ current exhibition Outside The [Box] (on view in the Nixon Gallery at the Smith College Museum of Art from July 27 to September 30, 2012). Gathering fifteen students together from across the country for a six-week museum boot camp, the SIAMS program is a Pandora’s box of sorts. It has certain defined limits – like the four sides of a box – that both contain and open onto innumerable and mysterious fragments of knowledge for its participants.

Coming from a range of schools, and having studied in a variety of disciplines, the fifteen students were brought together to live and learn every aspect of the daily life of a museum and its staff. In addition to weekly assignments, we were given a room, roughly thirty objects thematically selected by the Smith College Museum of Art, and the task of mounting all aspects of a professional exhibition. The fifteen became three groups of five, as the students were divided into teams to take on the tasks that would make up the exhibition: Curatorial, Design and Public Presentation, and Education.

As a member of the Curatorial Team, I had the opportunity to experience the difficulties that go into an exhibition’s conception. Handed a considerably large gallery and thirty-some boxes, or artworks related thereto, we were presented with a challenge in defining the thematic overview of the exhibition. How could we make such a seemingly banal, everyday object be seen as exciting and enticing? How were we to adequately address the differing cultural origins of many of the works, as well as being sensitive to alternative meanings given to the box within cultures?

As our conversation began, one piece we had been given quickly became a pivotal work: Master ZBM’s print, Pandora's Box. We latched onto the etching for the story it enclosed, rather than for a primarily aesthetic reason. We saw Pandora’s box as the first box, as a paradigmatic box. But more than this, we saw in the myth of Pandora an instance in which a box had served as more than a box, functioning outside the realm of the purely utilitarian. The underlying themes that became guiding for us in defining the parameters of the exhibition were the box as an object that could excite curiosity, and the box as an everyday object that would invite thoughtful reconsideration and reinterpretation.

The myth of Pandora is definitive in Western ideas of the box as an object of curiosity and a container of mysterious contents. The myth is also a prime example of the historical transformation of a particular box. Though “Pandora’s box” is a common idiom today, it was not always a box, but rather a large and immovable earthenware vessel. Pandora, linked with the Biblical Eve as a woman unable to avoid temptation, was taken up by the Fathers of the Church who were influential in the transmission of the myth and the transformation of her vessel into a box. Just as Eve was understood to be responsible for the fall of man in delivering the apple to Adam, so Pandora became responsible in turn, as her cumbersome vessel was turned into a portable box.

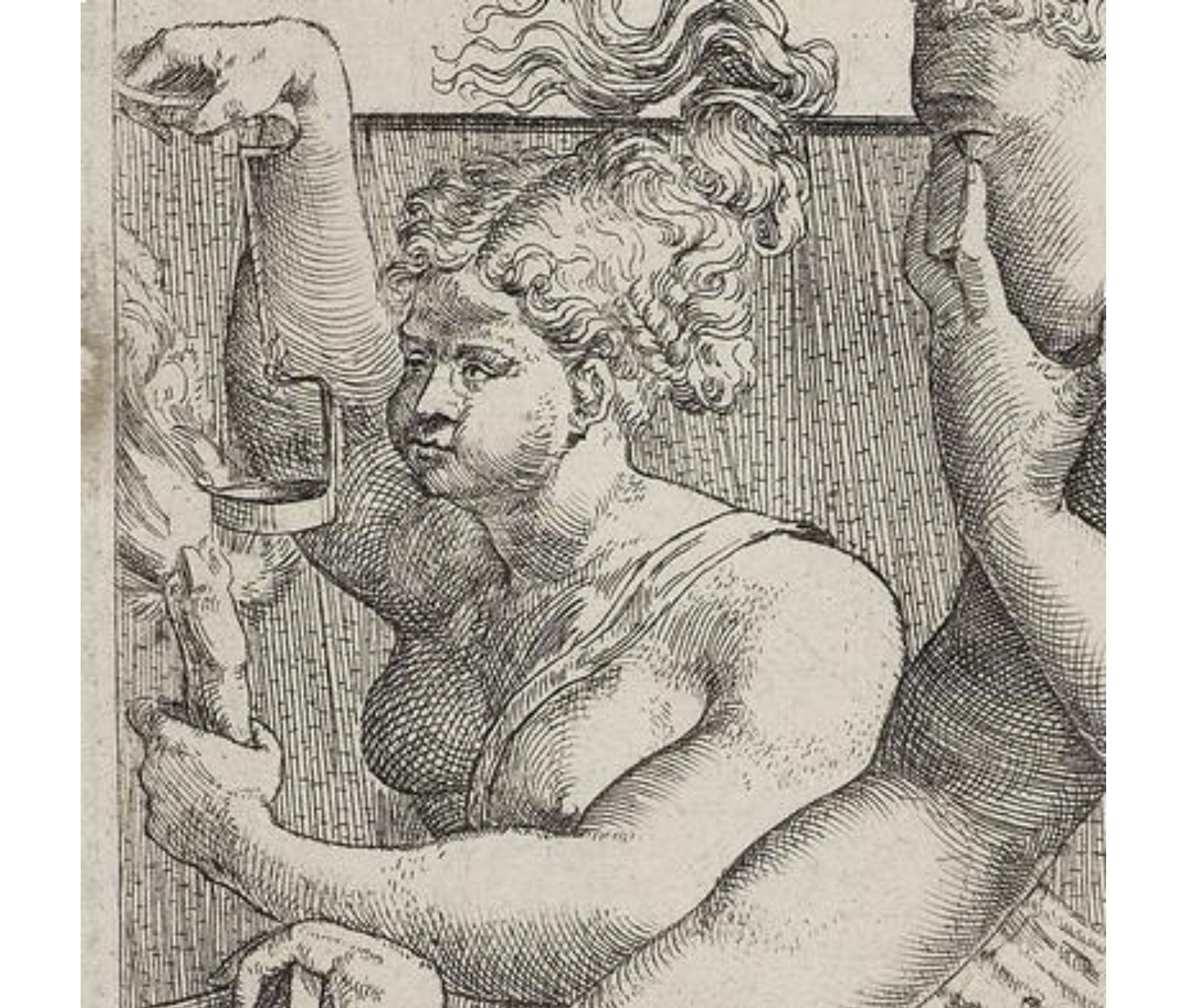

Detail from Pandora’s Box or An Allegory of Les Sciences qui Éclairent l'esprit de l'homme (The Sciences that Illuminate the Human Spirit)

Marco Angolo del Moro’s print differs from other representations of Pandora in three important ways, as lucidly described by art historians Dora and Erwin Panofsky in Pandora's Box: The Changing Aspects of a Mythical Symbol. First, though her box traditionally held exclusively good or evil, del Moro’s Pandora released a strange combination of both. From the box emerge symbols of evil, as well as symbols of knowledge. Second, the figure of Pandora is blind, as made clear by her hand gesture, which reveals the absence of pupils. Pandora is not acting upon willful curiosity, but rather unseeingly or unwittingly. Finally, Panofsky describes Pandora’s ignorant action is a blessing in disguise, setting “in motion the powers of light that drive away the creatures of darkness.” The powers of light are personified in the leftmost figure, with her alert gaze and brilliant torch (see above), and the sun-god Apollo, seated in the sky (see below). Apollo points to Aquarius, the zodiacal sign of January, which marks the “Ascent of the Sun” after the peak of winter, symbolizing, in Panofsky’s words, “the beginning of a new year and a new era.” Marco Angolo del Moro’s print allegorically portrays Pandora as Ignorance, an instrument of blind fate bringing about an age of light from which she herself is forever excluded.

Detail from Pandora’s Box or An Allegory of Les Sciences qui Éclairent l'esprit de l'homme (The Sciences that Illuminate the Human Spirit)

Beyond Apollo, and depicted in his infamous descent, is the angel Lucifer (see below). The inclusion of this Christian figure serves to make explicit the theological redefinition of the Pandora myth by the Fathers of the Church. Lucifer, in falling from the heavens, presents a visual analogy to the aforementioned fall of man. Del Moro’s etching, dated to 1557, coincides with the Renaissance and the revival of classical humanist ideals. The archetypal and all-knowing “Renaissance man” of the time presents an analogous embodiment of light to that of the torch holding figure beside Pandora. The print portrays the pursuit of knowledge during the Renaissance as a force of literal enlightenment combating the black night of ignorance feared by the Church. After all, “an idle mind is the Devil’s workshop.”

Detail from Pandora’s Box or An Allegory of Les Sciences qui Éclairent l'esprit de l'homme (The Sciences that Illuminate the Human Spirit)