The Photographic Imaginary

Guest blogger Julie Warchol is a graduate M.A. student in Modern Art History, Theory, and Criticism at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. She was the 2012-2013 Brown Post-Baccalaureate Curatorial Fellow.

While I often think back fondly on my days as the Brown Post-Baccalaureate Curatorial Fellow at SCMA, my current experience as a graduate student has offered me the wonderful opportunity to further research, study, and write about the prints, drawings, and photographs which I have encountered in SCMA’s collection. This spring semester, I considered Caroline Sturgis Tappan’s collection of Samuel Bourne photographs from India (now in the SCMA) as my seminar paper topic for a class on Orientalism in the nineteenth-century. An American Transcendentalist artist and poet, Tappan (1818—1888) amassed an impressive collection of over one thousand photographs primarily from throughout Europe, the Near East, Egypt, Japan, and India as a tourist throughout the 1850s to the 1870s. Interestingly, however, it appears that Tappan never actually traveled to either Japan or India. Focusing specifically on her photographs from India, this fact led me to wonder: What was Tappan’s interest in India and why might she have collected photographs of a country she never visited?

Samuel Bourne. British, 1834 –1912. Simla: General View from Jakko, ca. 1860s. Albumen print. Purchased with Hillyer-Tryon-Mather Fund, with funds given in memory of Nancy Newhall (Nancy Parker, class of 1930) and in honor of Beaumont Newhall, and with funds given in honor of Ruth Wedgwood Kennedy. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1982.38.312.

Tappan was a close lifelong friend of Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803—1882), who greatly influenced her Transcendentalist attitudes toward spirituality and nature. Emerson, who avidly read and revered ancient Hindu scriptures, seems to have shared his copy of the Bhagvat-Geeta (translated into English by Sir Charles Wilkins in 1785) with Tappan in 1845. After a visit to his home in Concord in 1845, she writes to Emerson from her summer home in Lenox, Massachusetts:

In this short but telling passage, Tappan romanticizes and quite directly associates the Bhagvat-Geeta both with Emerson himself and her solitary experiences in nature. One among the many topics discussed in the Bhagvat-Geeta is the Hindu belief in nature’s sacrality, which no doubt appealed to both Emerson’s and Tappan’s Transcendentalist beliefs. Literary scholar Kathleen Lawrence has shown that throughout their letters, Tappan and Emerson associate one another with moments of divine communion with nature due to their frequent private walks together in the Concord pine woods around Emerson’s home and Walden Pond. [2] Mere weeks after her visit to Concord when she read the Bhagvat-Geeta, Tappan relished in the opportunity to be alone in the Berkshire Mountains, that distinctive Western Massachusetts landscape which she calls “the solitude of the mountains.” In this instance, this mountainous landscape afforded her the much-welcomed opportunity to further contemplate the Hindu Bhagvat-Geeta, Emerson, and nature itself.

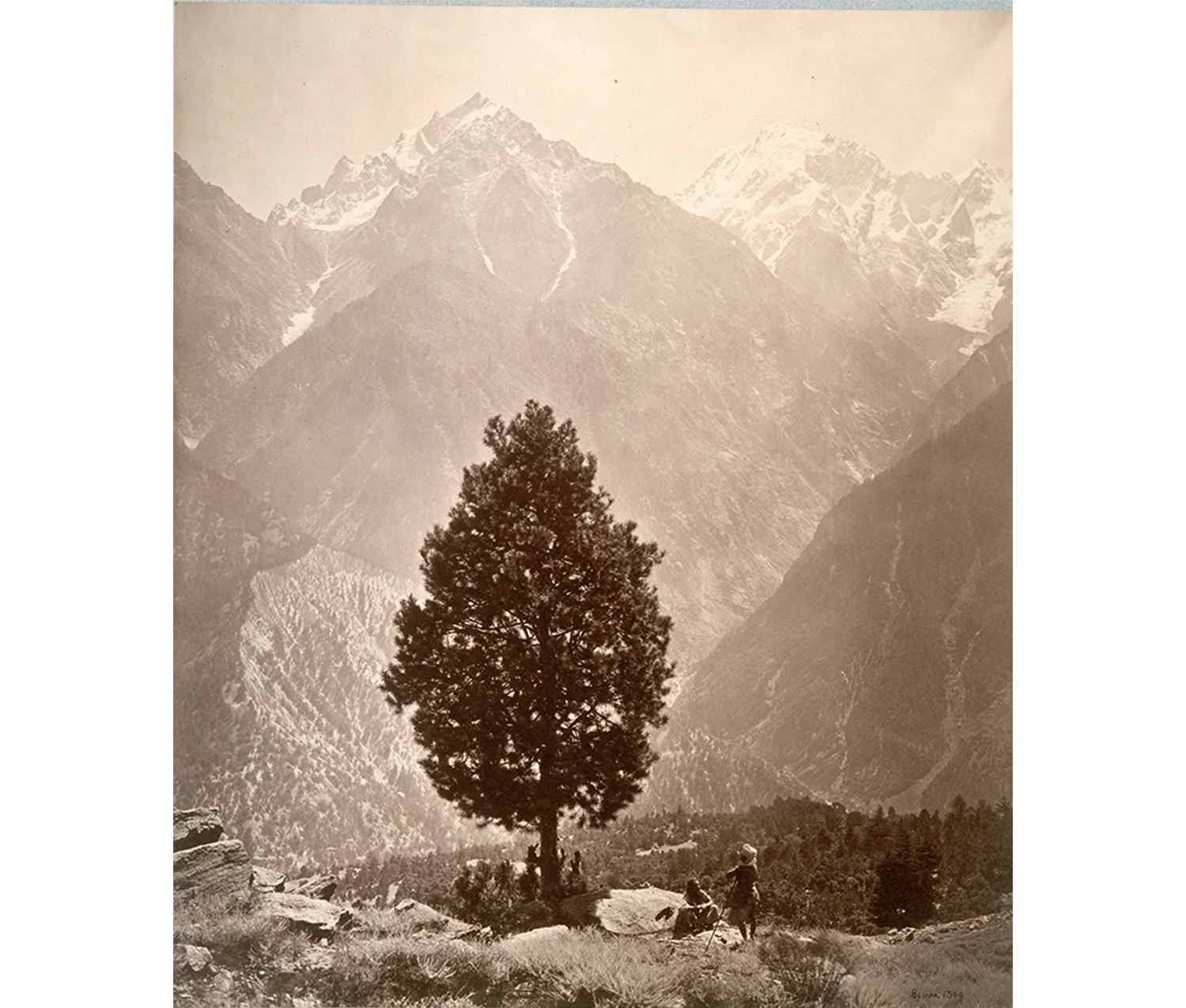

Samuel Bourne. British, 1834–1912. Specimen of the Edible Pine, ca. 1860s. Albumen print. Purchased with Hillyer-Tryon-Mather Fund, with funds given in memory of Nancy Newhall (Nancy Parker, class of 1930) and in honor of Beaumont Newhall, and with funds given in honor of Ruth Wedgwood Kennedy. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1982.38.335.

Collected some twenty-five years after she read the Bhagvat-Geeta, virtually all of Tappan’s photographs of India are the work of Samuel Bourne (1834—1912), the British photographer whose 1860s albumen photographs famously display the Indian landscape in the “picturesque” style common to British eighteenth- and nineteenth-century landscape painting. However breathtaking Bourne’s landscape photographs may be, they were rarely bought by Europeans who traveled to India. European tourists preferred Bourne’s photographs which depicted common tourist sites, such as India’s major cities and temple ruins. As she never traveled to India, however, Tappan most likely acquired these photographs through Bourne’s distributors in London or Paris and was attracted to his landscape photographs for personal and aesthetic reasons. While Tappan, as an educated member of upper class Boston society and an artist herself, was certainly well-versed in the picturesque aesthetic, I believe this only partially explains her interest in Bourne’s landscape photographs.

Samuel Bourne. British, 1834–1912. 1758: Simla Snow Scene, ca. 1860s. Albumen print. Purchased with Hillyer-Tryon-Mather Fund, with funds given in memory of Nancy Newhall (Nancy Parker, class of 1930) and in honor of Beaumont Newhall, and with funds given in honor of Ruth Wedgwood Kennedy. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1982.38.373.

Given the personal associations Tappan formed between the ancient Hindu Bhagvat-Geeta, Emerson, and nature in her 1845 letter mentioned above, it is notable that a large percentage of her Bourne photographs are his images of northern India’s Himalayan Mountains and pine forests. Curiously, these depictions show some superficial geographical resemblances to elements of the Massachusetts landscape which Tappan repeatedly romanticizes in her letters to Emerson dating from the 1840s to the 1870s—most particularly the Berkshire Mountains and Concord’s famous pine woods. In one of several such letters, Tappan writes to Emerson from Rome: “Do you not think I remember the Concord pine woods because I am here among the Italian cypresses[?] Mere cypresses will never wave to every breeze as the pine trees wave.” [3] For Tappan, pine trees and mountains were symbolic of her Massachusetts homeland, particularly during her years abroad.

Importantly for this consideration of Tappan’s interest in Indian landscape photographs, the picturesque aesthetic which Bourne and other photographers throughout the British Empire employed was a visual strategy for homogenizing foreign landscapes, in effect making them appear rather similar to the homelands of European and Anglo-American tourists. [4] For instance, in Bourne’s Simla Snow Scene (shown above), Tappan might see an exotic India through its unfamiliar-looking houses and fences, but could have imaginatively projected herself into the role of those tiny figures to mentally relive her numerous prior experiences walking through such snow-covered pine forests in Concord, Massachusetts. Similarly, when viewing Bourne’s Mountain with Lake (shown below), she might have been reminded of both her walks to the similarly tree-enclosed Walden Pond with Emerson or even her solitary experience in Lenox when she rowed out onto a lake amidst the forests and Berkshire mountains to contemplate the Bhagvat-Geeta and nature’s sacrality in 1845. While Tappan may have been physically located in Europe when she acquired these photographs in the late 1860s or early 1870s, her Bourne landscape photographs offered her the opportunity for such romanticized and imaginary aesthetic experiences of both Massachusetts and India, the land she had temporarily left and another to which she would never travel.

Samuel Bourne. British, 1834–1912. Mountain with Lake, ca. 1860s. Albumen print. Purchased with Hillyer-Tryon-Mather Fund, with funds given in memory of Nancy Newhall (Nancy Parker, class of 1930) and in honor of Beaumont Newhall, and with funds given in honor of Ruth Wedgwood Kennedy. Photography by Petegorsky/Gipe. SC 1982.38.296.

[1] Eleanor M. Tilton, ed., The Letters of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Volume 8 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 27, n. 86.

[2] For more on Tappan and Emerson’s relationship, see Kathleen Lawrence, “The ‘Dry-Lighted Soul’ Ignites: Emerson and His Soul-Mate Caroline Sturgis As Seen in Her Houghton Manuscripts,” in Harvard Library Bulletin 16, no. 3 (Fall 2005).

[3] Sturgis-Tappan Family Papers, Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College, Northampton, MA (autograph letter: Tappan to Emerson, May 23, 1857).

[4] Jeffrey Auerbach, “The Picturesque and the Homogenisation of Empire,” in The British Art Journal 5:1 (Spring/Summer 2004): 47-54.